With a continual torrent of rain and grapple pelting my rainfly I burrowed deeper into my sleeping bag. I had been holed up in my little nylon sanctuary for several hours and the steady assault levied by an early winter storm indicated I had many more hours to go. I didn’t care. I had a good tent, warm bag, and comfy sleeping pad, and was enjoying a solid excuse to catch up on much-needed rest.

For the tenth year in a row I had once again journeyed deep into the mountains of Southern Colorado at the nexus of autumn and winter. My favorite of the shoulder seasons, it can be full of weathered drama if not a little unforgiving. Despite the duration of the storm keeping me tent-bound through the night, it was mild enough to only leave behind a dusting of wet snow. I’ve fared far worse in years past.

As a frequent visitor to the peaks and valleys around Silverton, I have developed an appreciation for its many hidden secrets. Most people to vacation in this part of Colorado only come for the sweeping views, the challenging roads, and the chance to stroll through the tourist shops to buy T-shirts and souvenirs. They drive their rented Jeeps and ATVs past the many old abandoned mines and cabins stopping only to snap a quick selfie before pressing on.

As a frequent visitor to the peaks and valleys around Silverton, I have developed an appreciation for its many hidden secrets. Most people to vacation in this part of Colorado only come for the sweeping views, the challenging roads, and the chance to stroll through the tourist shops to buy T-shirts and souvenirs. They drive their rented Jeeps and ATVs past the many old abandoned mines and cabins stopping only to snap a quick selfie before pressing on.

I don’t really blame them. Not everyone is like me, a pedantic history nerd incapable of passing by an old barn without wondering who built it, what they did within it, and why they left it to rot. Fortunately for me, the sprawl of mountains around Silverton is awash in interesting stories, some literally ripped from the pages of a dime store novel.

After packing up my wet tent and loading my bike, I started to push higher into the peaks. I turned onto a narrow road leading upward toward Hurricane Pass, the steepness of the grade proving a tough go for my already tired muscles. My objective for the day was a seldom traveled road which attained a saddle between two 13,000 foot peaks. To the southwest was Bonita Peak, to the Northeast the jumble of rock called Hanson Peak. Most of the people who travel that small road only do so to gain the expansive views. I had a more specific goal, to get a bird’s eye view of the valley below.

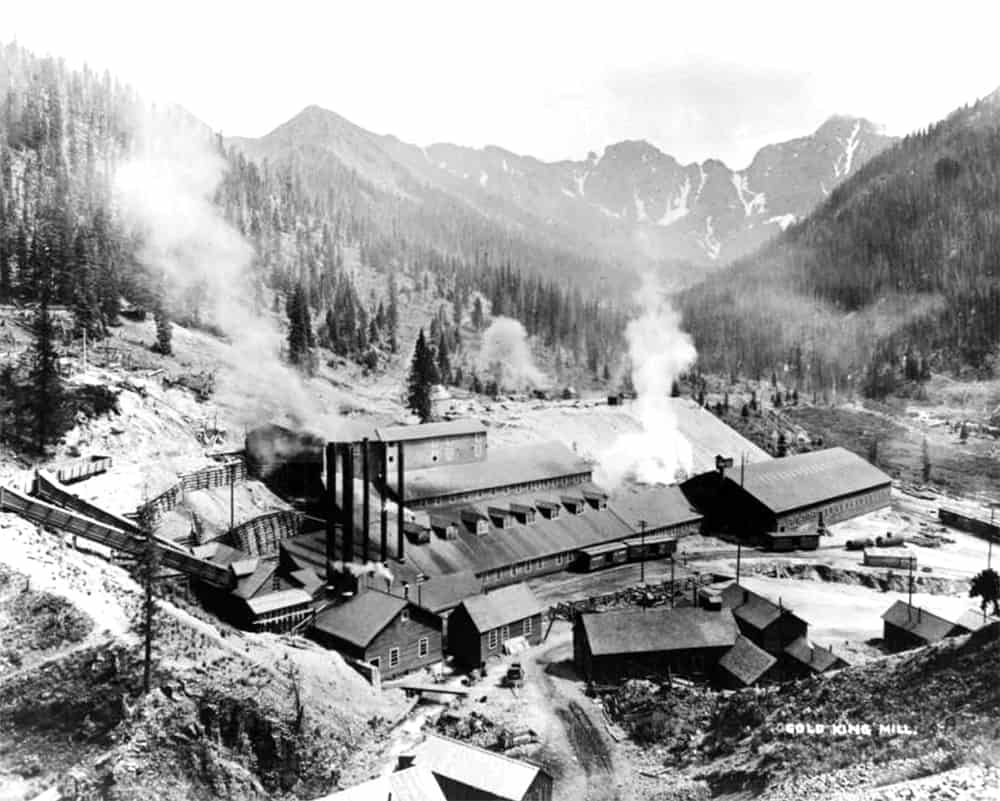

Although only a few miles into my ride, one that took hours of slow grinding and multiple stops to catch my breath, I arrived at a 12,000-foot pass overlooking Eureka Gulch several thousand feet below. I dismounted my bike, ducked behind a boulder to escape the biting wind, and unpacked a small bag of snacks. Gazing down at the warren of roads below, some of them ending at piles of rubble, it was hard to imagine what the valley looked like in the late 1800s when it was the site of the active Sunnyside Mine.

Although only a few miles into my ride, one that took hours of slow grinding and multiple stops to catch my breath, I arrived at a 12,000-foot pass overlooking Eureka Gulch several thousand feet below. I dismounted my bike, ducked behind a boulder to escape the biting wind, and unpacked a small bag of snacks. Gazing down at the warren of roads below, some of them ending at piles of rubble, it was hard to imagine what the valley looked like in the late 1800s when it was the site of the active Sunnyside Mine.

It was in 1873 when famous prospectors George Howard and R.J. McNutt discovered a silver vein in Eureka Gulch, a find that would spark the formation of the mine. Less then 10 years later in 1882 they discovered gold, and within short order the small valley scarcely a mile square was choked with mining operations. This wasn’t the first, nor the last time fortunes would be sought, found, and lost in the San Juan Mountains.

With my lunch consumed I worked my way down the western edge of Bonita Peak to the juncture with County Road 20. I resumed my climb upward yet again, this time arriving at the 12,000-foot pass above Lake Como and Poughkeepsie Gulch. A famous route for hardened off-roaders, the history of prospecting in the deep valley predates that of Eureka Gulch by as many as 150 years. It’s easy to think of the mining years as those in the late 1800s, but the Spaniards were the first to scratch at the soil in search of riches. Archaeological evidence and historical records point to 1760 as the year the Spanish first began exploring for gold and silver. The primary reason many would-be prospectors never found their fortunes in the San Juans has much to do with Chief Ouray and his control over the region. It wasn’t until well after the 1860s when whites were allowed to travel freely in the land of the Ute Nation, let alone pluck its riches from their sacred mountains.

With my wheels bouncing deeper into Poughkeepsie Gulch it didn’t take long before I was once again climbing, this time on the agonizing switchbacks of Forest Road 878. With daylight fading, and storm clouds building, I ducked into the trees and once again set up camp. Collapsing in a pile, barely able to muster the energy to chew my dinner, I listened to the rain once again patter against my rainfly.

With only another day’s riding left in me, I picked my way around more switchbacks and passed the San Juan Old Chief Mill before arriving at the base of Engineer Pass. I stopped to snack on my last stashes of food and reflected on another historical oddity of the region: the story of the Cannibal of the San Juans.

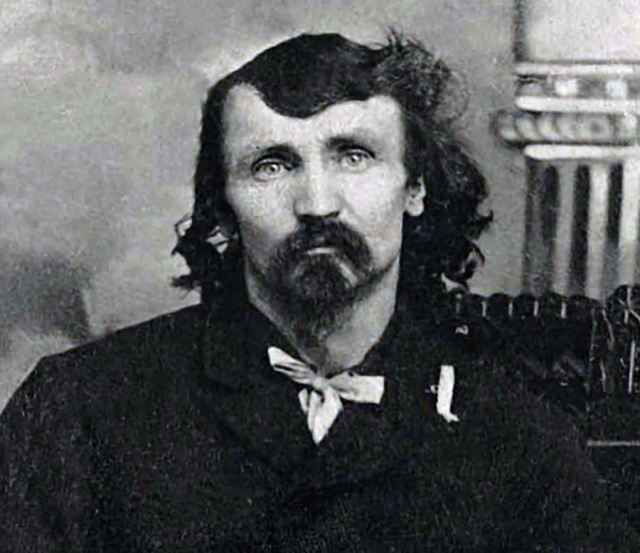

It was in the winter of 1874 when Alfred Packer entered the mountains with five other prospectors. Not much is known of what transpired in the mountains west of Lake City, but eventually only one of the six exited the backcountry. Looking none the worse for the hardships he claimed to have endured, Packer not only looked plump and well fed, he had on his person a number of items belonging to his absent travel mates. Chief Ouray immediately sensed something was amiss and before long he dispatched scouts to search for the missing men. Only parts of them were found.

Alfred Packer

The story of Alfred Packer has been immortalized in books, musicals, songs, and endless retellings of the tale around campfires throughout Colorado. Packer somehow managed to avoid the hangman’s noose, and died a parolee in 1907.

My own appetite inexplicably suppressed, I continued on to Lake City, over Cinnamon Pass, and back into Animas Forks where a gaggle of tourists in rented side-by-sides ambled about the ruins of the old mining operation. In the parking area below, a young hooligan drove in erratic circles, a spray of rocks and dust shooting in all directions. The ghosts of the place must not have been amused. Before the ill-behaved tourist could do more damage, the right rear tire blew bringing his shenanigans to an abrupt halt. There’s a fine line between tourist and miscreant in this part of the world.

After a quick check of my watch I deduced it was time to pull the plug on my trip. My legs were tired, my pack empty of food, and the beers in Silverton were calling my name. I pedaled the last few miles into town, past more old mines, a few vacant cabins, and the remnants of the rail line that once serviced a thriving mining operation. Rolling into town, I stopped to admire a few of my favorite old buildings. How fun it would have been to see it long before the T-shirt shops and ice cream parlors took over.

The Old West is still there if you know where to look for it and care to see it. You’ll have to conjure it up with a little research and imagination, but if you take the time to read about it, the history of Silverton and the surrounding peaks will keep you coming back for more. – CN

The Old West is still there if you know where to look for it and care to see it. You’ll have to conjure it up with a little research and imagination, but if you take the time to read about it, the history of Silverton and the surrounding peaks will keep you coming back for more. – CN