Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Fall 2020 issue.

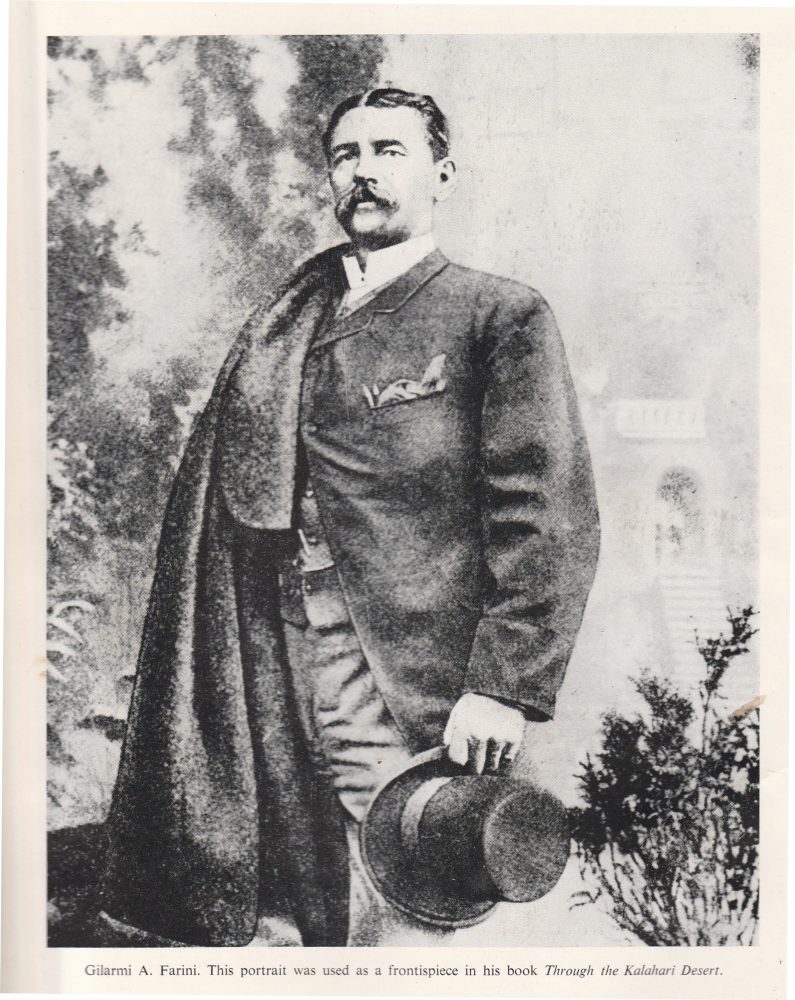

On an evening in July 1985, Fat Paul Wonsok met Bros at Stan’s Bar at the Babanango Hotel in distant Zululand. Wonsok, so named because a goat once ate his other sock, had a proposal. Over brandy, he spoke of the Kgalagadi, the great semidesert of Botswana, which was reputed to harbour a lost city. Fat Paul had read books on the subject, including, Through the Kalahari Desert, by Gilarmi A. Farini, who reported discovering the ruins in 1885.

The Lost City of the Kalahari has since figured in the imaginings of many who have wandered about the wastes of the Kalahari, or Kgalagadi as it is now known, searching for the stone walls, courtyards, and terraces first reported by Farini. Lost cities, tombs, and treasures were usually discovered by chance, or by explorers after years of research, deciphering hieroglyphics, and digging, said Wonsok. He proposed they go in search of the place. Bros was ideally suited for the job—he had been a mineral prospector and studied archaeology at university.

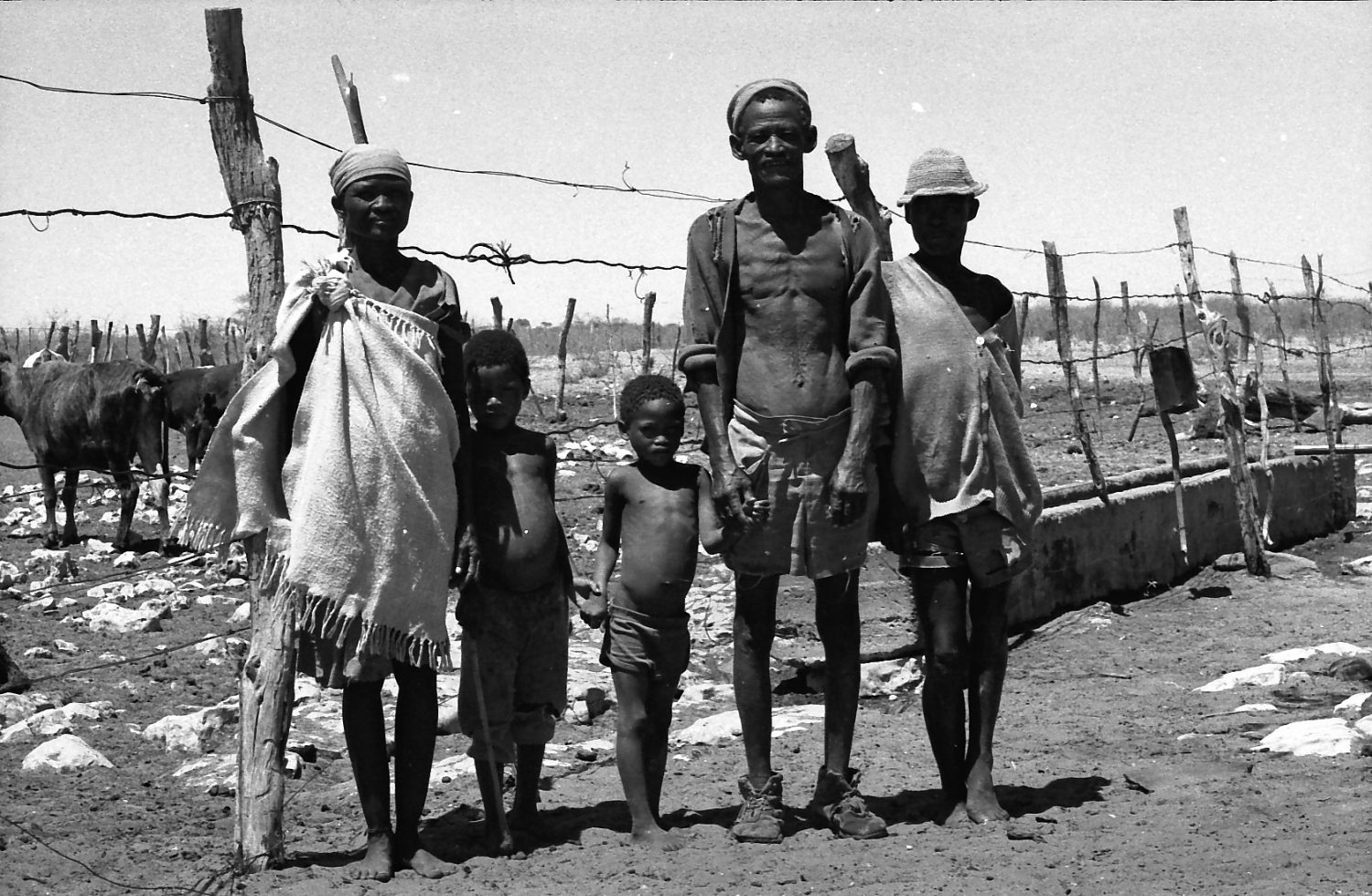

In February 1885, Gilarmi Farini, proprietor of the Royal Aquarium in Westminster, London, embarked on an expedition to the Kalahari to coerce members of the San people, known as Bushmen at the time, to return with him and complement other exotica featured at his aquarium. On display were such things as Farini’s Earthmen (African Pygmies), a group of Zulus, a mermaid, a preserved whale, a fat lady with a moustache, and a creature labelled Krao, the Missing Link. Some people suggested that the real reason for Farini’s expedition was to find diamonds.

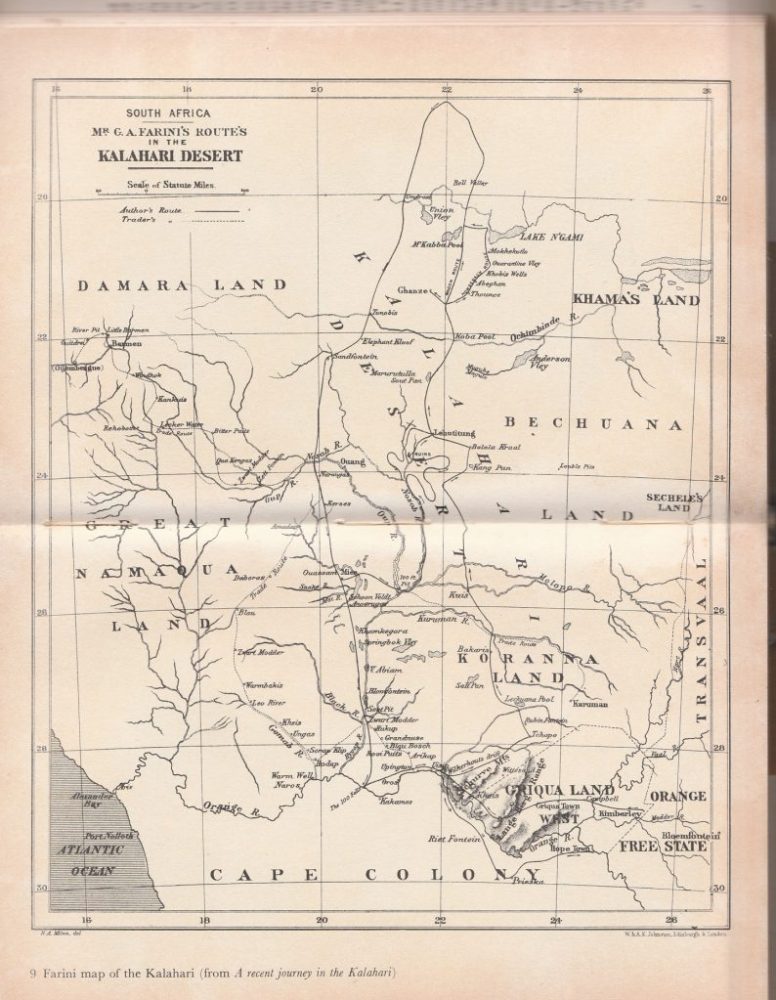

Born in New York as William Leonard Hunt, Farini once crossed the Chaudière Falls in Canada by tightrope, a feat which led him to style himself as Farini the Great. He and his son Lulu arrived in Cape Town and set off by train to Kimberley. From there, he journeyed to Upington in the Northern Cape, and with local guides and well-loaded ox wagons went up the Nossop River, the southwestern boundary of Botswana, and into the Kgalakgadi to lure Bushmen to London. On his return, Farini claimed to have found the ruins of an ancient city in the desert, and in the following year, published his book and lectured both the Royal Geographical Societies in London and Berlin on his discovery.

The first to report having looked for Farini’s Lost City was one Albert Albath, who tramped about the scrub of the bone-dry Kalagadi in 1942. But beyond being frightened by a lion chasing his donkey, he had little to show for his experience. Some years later, the French explorer François Balsan too wandered around the desert on donkeys, and too saw little more than scrub, yellow grass, and herds of zebra and wildebeest, but fortunately, no lions. Subsequently, the SIMCA Motor Company sponsored him with two four-wheel-drive lorries fitted with large tyres to enable the discovery of the elusive city. He again returned in despair. The Haldeman family from Pretoria also spent fruitless years looking for the legendary place, using Jeeps and a Navion aircraft. Haldeman even persuaded the South African Air Force to provide a C-47 Dakota to help in the search.

“Happily,” said Wonsok, “the Lost City is still lost, for what adventure is ever to be had looking for a Found City, unless the allure be dancing girls? No, no self-respecting lost city would ever simply reveal itself. Its discovery would surely be the result of a momentous event.”

And, said Wonsok, now was the time of a momentous event, for it was a hundred years since Farini had made his discovery. And now, after a century, the Lost City should surely rise from the sands. They should mount an expedition. He would invite some girls along.

So it was on a day in early September 1985, almost exactly 100 years after Farini’s discovery, all gathered at Wonsok’s home in Dundee, a nondescript joint of a town in Northern Natal. Jane and Jackson had been invited to liven up proceedings and provide entertainment. Jane was Bros’ sister, an accomplished artist and guitarist, while Jackson could recite “The Ballad of Eskimo Nell” chapter and verse, told worse jokes, and could change a wheel.

Fat Paul’s preferred packhorse was a Land Rover—a well-worn 4-cylinder Series 2A, a three-door hardtop van of 1963 vintage. It was loaded with food and not a little drink, water, petrol, kit and caboodle, spares including extra spare wheels, and mattresses and a large tarpaulin to sleep on. Wonsok had panelled the interior of the Land Rover with dark stained plywood, “to give it a bit of a classy look,” he declared, “like a classic Jaguar.” Jackson was favoured for some reason, so Bros and Jane rode in the back, lying on mattresses laid on the load. “Like travelling in an old wardrobe,” declared Jane.

Wonsok had a theory on how to find the Lost City west of Khoti Pan. He had come to this after donning his Boy Scout hat, scarf and woggle, consulting oracles, looking into a mirror, and inhaling the smoke from smouldering imphepu leaves while intoning, “Bhebha bonke, bhebha tonki, bhebha bonke, bhebha tonki,” the meaning of which words are only known to some witch doctors. He had made calculations using a map and a ruler as there was no such nonsense as a GPS in those days. “It should be right here,” he said, jabbing at a 1:250,000 topographical map of Southwest Botswana with a finger which had recently taken part in the overhaul of some mechanical component or other. The map was a largish sheet of blank paper with impressive borders, official titles, numbers, and little else—a vague line representing some contour meandered diffidently over the page. Beyond odd spot heights, and a greasy finger smudge, there was nothing else shown.

They set off west on what was to become a grand adventure and crossed into Botswana at Lobatse. After a beer or two at the Cumberland Hotel, the dry country of grassland and scrub drew them south to Pitsane, and on toward Makgobistad, from where they took the southern border road west. It was decided to spend the night in the bush before filling up with fuel and water at Bray. Here, they turned north on a sand track through dry scrub. Some kilometres south of the tiny settlement of Khakhea, little more than a well and a collection of huts and tin shacks, they turned due west to follow an old prospecting cutline which Wonsok calculated would bring them close to where the Lost City lay. The turnoff was marked by a faded Lucky Strike packet stuck in a bush.

The cutline took them into increasingly sandy country, over low dunes and across salt pans, which necessitated four-wheel drive. They camped in wild country, drank brandy and coke, and told lion stories. They had acquired a bloody lump of wildebeest from some hunters after assisting them with a broken-down Land Cruiser. The ignition wire was loose on the coil, and knowing food, and how to cook it, Wonsok dished up wildebeest au vin, with soupe des onions and croutons, and crêpes Suzette for dessert.

The next day brought soft sand, bigger dunes, and more dry salt pans. While traversing a particularly difficult dune, the four-wheel drive decided to retire. The splines on the left-hand front-wheel driving flange had stripped, and, of course, there was no spare. It was decided a four-wheel drive would be useful, indeed essential for their venture into Parts Unknown by Those of Faint Heart. They would need to get spares. Heading on for some hours, they found the main north–south track from Tshabong near the South African border to Lokgwabe, a village 70 kilometres of sand track to the north, and a short distance further to Hukuntsi, where Prins’ store stocked everything. The tyres were deflated somewhat to give better flotation and traction in two-wheel drive in the miles of soft, loose sand which lay ahead.

Prins’ store indeed had everything, but no Land Rover spares, so they carried on to Kang, another long way away to the north, where there were no Land Rover spares either. At Kang, they were now on the main east–west road in southern Botswana, which ran from Lobatse to Ghanzi and on to Gobabis on the Namibian border. This was a most tediously awful dirt track used by heavy trucks carrying cattle to the abattoir in Lobatse. Ghanzi lay 300 kilometres of dust and sand and more bad language and brandy northwest to Lone Tree and beyond. Ghanzi had no Land Rover drive flanges either.

The hospitable barman at the Kalahari Arms served the coldest beer and recommended the bar special of steak. He spoke of the Kgalagadi and explained the roads through the deep sand were originally made by wide-track Ford, Chevrolet, and Bedford trucks. Land Rovers were hardly seen there because they were narrow, did not track, battled along, boiled, and got stuck and broke. So Land Rovers kept out of the Kgalagadi, and spares were never stocked. Spares could be had in Maun, where Land Rovers were commonly used.

The merry band headed on and banged and rattled their way north. After a night spent in the bush near the Aha Hills, they carried on for some hundreds of kilometres further north to the tourist centre of Maun.

Maun is also the administrative centre for Northwest Botswana and lies on the Thamalakane River, which drains the wonderland of the Okavango Delta. It was an absolute paradise of water, greenery, trees, and every kind of wild game after the dust, stones, and grey thorn scrub of the Kgalagadi. There, Land Rovers were as common as goats.

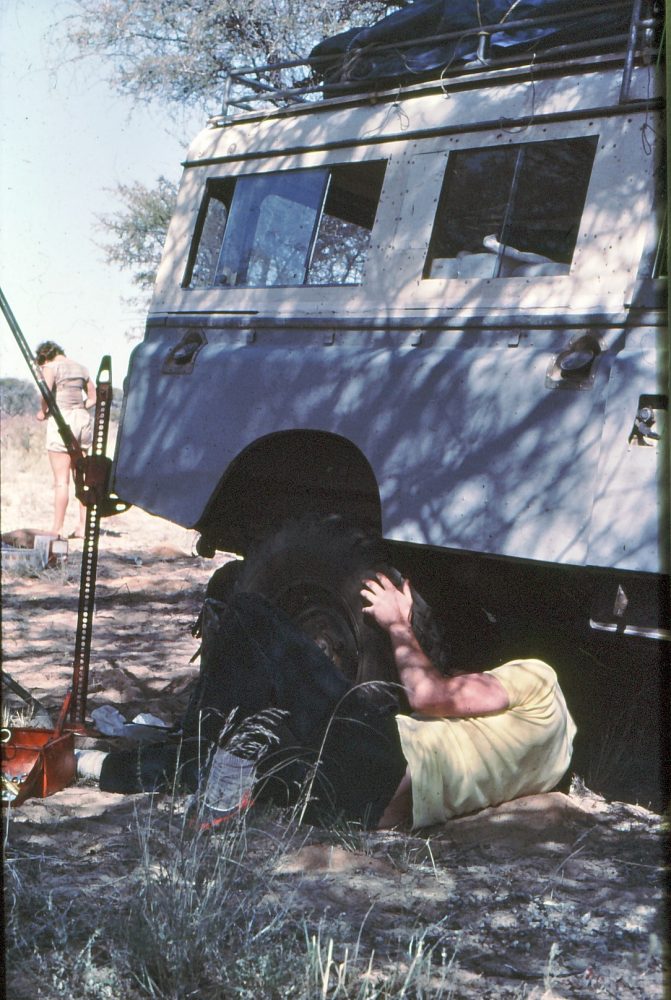

Riley’s Garage in Maun had new drive flanges, and Riley’s Hotel had the coldest beer, enjoyed under magnificent trees on the banks of the Thamalakane. They camped at Croc Camp, and Wonsok put right that which was wrong with his four-wheel drive. During the hours he was busy beneath the front axle, Jane acquired some white acrylic paint from the camp manager, and unseen by the vehicle’s proprietor, painted over the Land Rover’s varnished interior panelling. The gloomy wardrobe-like interior was transformed into bright and cheery quarters. Fat Paul was, of course, horrified at this desecration of his vehicle, but cheered up and served crocodile biryani for supper.

On the rest of the trip, Bros and Jane painted watercolour sketches of people and incidents encountered on the trip, using the white painted panels as a canvas. The Land Rover became a sort of mobile Sistine Chapel.

Around the campfire, they discussed their immediate future. A hunter friend in Maun had told them of another supposed lost city at Lekhubu, a rocky hill in the middle of the Makgadikgadi, the great salt pans, once an inland sea, covering over 10,000 square kilometres in central Botswana. “Let’s go there,” said Wonsok, “it is a detour, but as we know, it is not right to travel the road already travelled, so we take another, see Lekhubu, and then head back through the Kalahari to find Farini’s Lost City.”

Accordingly, the next morning they took the main road east to Nata, to spend the night at Sua, on the northern edge of the Makagadikgadi. There was water on the pan, and the place was alive with water birds, flamingos, pelicans, herons, stilts, and duck. The following day, they battled south following the edge of the Makagadikgadi, at times having to cross parts of the pan, getting stuck and jacking with a Hi-Lift jack, packing rocks and scrub to get going again. They then found a little-used track that took them to Lekhubu, altogether a day’s journey of but 140 kilometres of difficult going.

Lekhubu was an amazing place of granite outcrops, baobabs, and evidence of man’s occupation in the past when central Botswana was a vast inland lake and Lekhubu an island paradise, named for the proliferation of hippopotamus once found there. The next morning Fat Paul, Bros, and Jackson explored the island. Jane had other plans, and in Wonsok’s absence, she painted FAT PAUL WONSOK LOST CITY GREASY GARBONZA BAR AND RESTAURANT on the Land Rover’s doors. She had to placate him with brandy and their last coke.

The following day, they headed south across the pans, through dust as fine as powder some 60 kilometres to the village of Tlalamabele. From there, it was on to Orapa, the world’s largest diamond mine by area, 40 kilometres west to fill up on petrol, water, and supplies.

From Orapa, they headed to Mopipi, where they turned south, following a faint track to the dried-up Lake Xau, and following cattle tracks for 20 kilometres or so, found Kedia Hill seen above the distant bush. Kedia Hill is a sandy imminence with a survey beacon on top of it, the only hill of any significance anywhere near the Makgadikgadi. Many years before, a survey team had graded a road from the beacon on the summit of Kedia Hill for 160 kilometres to the west. Wonsok’s plan was to follow it to enter the Central Kgalagadi, and then to find the dry bed of the Okwa River and follow it southwest to the Ghanzi–Lobatse road. Then they would head back into the Southern Kgalagadi to find where Farini’s Lost City lay hidden. Kedia Hill and its cut line were known datums from which they could navigate with certainty, as the Kgalagadi was crisscrossed with tracks and paths which went to who knows where, and were not shown on any map, and, these were the days before Google Earth.

There was no road nor track to the summit of Kedia Hill, and the Land Rover, even with the four-wheel drive now working, battled through thick sand to reach the top of the hill. The beacon was found, and there too was the cut line, overgrown by grass and scrub, but running straight to the west. This they followed.

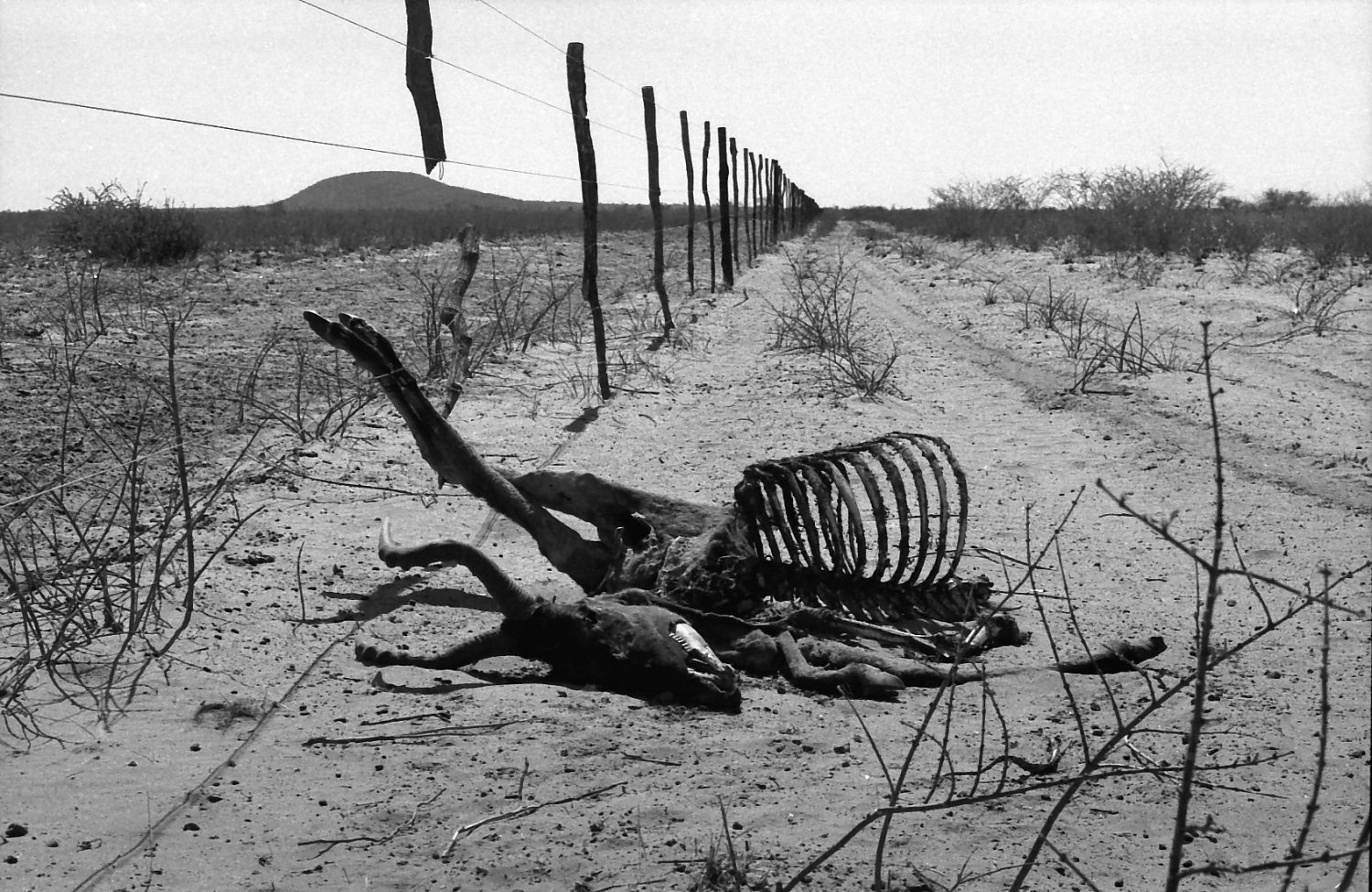

As they headed down the survey track, other tracks joined. The track, which now became a road, was fenced on the southern side. This fence was the cause of much controversy, for it prevented game in the Kgalagadi from moving to water at Lake Xau and Mopipi during the dry winter months. It was festooned by the dried-out remains of animals, wildebeest, hartebeest, and zebra trapped while trying to get to water. After some 50 kilometres, the boundary of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve was found, marked by a lonely faded signpost. Here, the map was consulted. The plan was to drive about 15 kilometres southeast down the cutline that demarcated the reserve boundary. There they should enter a valley which was the dry bed of the Okwa, a paleo river which had once drained the inland sea of Central Botswana, and follow its long dry bed southwest to the Ghanzi–Lobatse Road, a 180-kilometre run across the country. A short jaunt of about 20 kilometres would bring them to the track south to Hukuntsi and Mabuasehube to find Farini’s Lost City.

Following the reserve cutline southeast, they found the Okwa Valley and stopped to consider the situation. Accurate navigation by compass and odometer was essential if they were going to come out on the Ghanzi Road. There was certainly no road here, just long grass to clog the radiator, and scrub and bush to promote punctures, all interspersed by clumps of shady acacia trees.

The group was quite alone, with a 22-year-old Land Rover which overheated and had to be hand-cranked to start. Game such as wildebeest, zebra, duiker, and hartebeest was plentiful, with lion tracks frequently seen.

The Okwa riverbed wound and twisted about with side channels and valleys, all serving to confuse the issue. After an hour or so, Wonsok stopped for a consultation. Bros had his nose glued to the map and had been following every twist and turn the vehicle made as it made its way through the bush of the valley floor. The valley had now opened out, and there were numerous possible routes to follow. The rest of the day was spent picking their way southwestward, taking careful compass bearings on distant trees, and marking their progress across the featureless topographical map by referring to the odometer and a ruler. The Land Rover bulldozed its way forward, crashing through scrub, tall yellow grass, over small trees, and across numerous flat grey pans. A tailwind had the engine overheating badly, with them travelling for many miles with the bonnet open trying to cool the engine.

Camp was made in a clump of bush where they stopped for the night. And then came wind, black clouds, and lightning and thunder—awful in its violence and rain that lashed them with fury as they sat in the Land Rover, water dripping from holes and apertures. The storm went on its way, and the Kgalagadi became wondrously still. Stars came out, and the smell of wet earth and bush was as the strongest perfume. Jane serenaded the night with her guitar, while Wonsok prepared something Italian with meatballs, tomatoes, and spaghetti. Jackals yelped, hyena whooped, and more lion stories were told by the fire. Tracks in the morning told of lions round the camp in the dark.

The Ghanzi–Lobatse road was found at the midpoint of the next day. Theirs had been an epic trek through the trackless bush, dry grass, and sand. After turning and heading southeast down the main Lobatse road for 30 kilometres or so, they reached a spot marked on the map as Takaatshwane. Here was not even a signboard, but a track to follow south through heavy sand for Lehututu and places beyond. A burned-out Land Rover amused them for a while the next morning, and brought home the hazards of driving through grass that could pack around the exhaust to send one trailing flames behind them down the road. The track crossed numerous pans and a huge sand ridge where they repaired a puncture before passing the scattering of huts marking the village of Lehututu. Much later, as evening darkened the land, camp was found on the ridge on the southern side of Mabuasehube Pan—contentment settled in as they were now where they wanted to be.

Wonsok dished up garlic soup, a paella of tinned mussels, oysters and ham, salade de naranja, and a trifle of fruit and boudoir biscuits soaked in sherry and custard for dinner while a lion coughed in a gully behind them. Rather than sleep in the open, as was their wont, they hung their ad hoc tarpaulin tent from the Land Rover. Bros played a spotlight across the pan to see the reflected eyes of springbuck and springhares rising and falling as they hopped. A jackal scurried away, along with hartebeest and wildebeest, and then the lion, no doubt bored with coughing at them, moving off to find other amusement.

Some days were spent exploring to the west near the Namibian border where Farini had once been. Then a fast stuck in very thick sand, as the four-wheel drive had given up again. Wonsok was of the opinion that the front axle was bent, which caused the side shaft to wear away the splines on the drive flange. He was confident of his ability in two-wheel drive, and so let matters be. If necessary, he would replace the worn-away driving flange with one of the spares he had bought in Maun. They drove on into a land of pans, dunes, yellow grass, and dead trees, groaning under communal weaver’s nests, and were most excited to see pygmy falcons. Somewhere near the Namibian border, they stopped. They must have crossed the route followed by Farini a hundred years before, as there were things to be seen that astonished them.

Back at Mabuasehube some days later, they celebrated their success, and Jane played her guitar, howling songs to the moon while brown hyenas put in an appearance. They were due home in Natal, so decided to drive on through the night. At the time, the hundred or so kilometres of road south from Mabuasehube to Werda on the Cape border crossed an area many kilometres across of very deep sand. Negotiating this lot at one o’clock in the morning in a two-wheel-drive Land Rover was more fun than could be asked for.

They arrived back in Dundee on a Sunday night, pleased with their endeavour. There had been so much to find, see, and learn. Of what they now knew, and what was found they have kept to themselves. And the Lost City of the Kalahari? Well, it is still lost, and long may it remain so, for there is no fun in a Found City.