It took Coen 10 minutes to clear the roof, hood, and winch of a thick layer of snow. It had become part of a ritual now that we were on Hokkaido, the northernmost and coldest island of Japan, in the middle of the winter. Meanwhile, I packed everything away inside the Land Cruiser. The engine jumped to life—it had no problem with the Siberian temperatures—and we left the city of Asahikawa. Snowplows had worked all night, and the roads were clear. During winter months, fishermen and farmers swap their fishing and agricultural jobs to drive snowplows that work 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Over our 7-week stay on the island we were impressed with how they kept up with the neverending snowfall.

A turnoff took us into the mountains. Here asphalt was covered in snow, which the Land Cruiser handled very well, thanks to our friend Masa. On our arrival in Japan we had shared our winter plans with Masa, who lives on Kyushu Island in the south. He had looked at the Land Cruiser’s tires, concluded they wouldn’t do, and bought secondhand, studless tires online that had been waiting for us near Tokio at a friend’s place just before we’d hit the snow. We were grateful. These tires performed excellently. At one time, on a 6-degree slope, Coen turned off the engine and stepped outside to take a picture. As he put his food on the ice-glazed road, he lost his footing. The tires, by contrast, had no problem getting our car—weighing 3 tons—uphill, albeit to get going we engaged four-wheel drive. However, once the motion was there, the Land Cruiser performed beautifully. All over Hokkaido we drove on snowy, icy roads in two-wheel drive and the car didn’t slip once.

Hokkaido is often flat along the coast, but its interior is mountainous and includes Daisetsuzan National Park. In summer, the region must be gorgeous and easy to explore on hiking trails that are closed during winter. The landscape blanketed in snow had its own magic but was largely inaccessible, which was the sole downside of our decision to visit this island in winter. Not just hiking trails but many of the narrowest, windiest roads were closed off throughout winter.

The Blue Lake

We parked the Land Cruiser, put on jackets and scarfs, and stuffed small self-heating packs in our shoes. These packs are for sale in different sizes and easy to find everywhere in Japan, such as in convenience stores. We strolled down the road to the Blue Lake, now white. From here, a wide footpath followed the frozen water dotted with dead tree trunks. It continued along a river that was still flowing because hot water came pouring out of the slope at regular intervals. Due to its subterranean volcanic activity, Japan has thousands of hot-water sources and many have been turned into hot springs; obviously, we regularly took a dip in these scalding hot waters. Only meters from one such inflow of hot water into the river a frozen waterfall clung to the slope.

With snow muting all sounds, our world was silent except for the crunching of our shoes on the ground underfoot. The branches of the trees along both sides of the path were covered with a fresh layer of snow and dollops fell on our heads. We hiked the same path that evening, this time to see an actual Blue Lake. Well, for seconds, at least. Every evening the lake was lit in a rotation of colors. Tacky on one hand, especially when lit in red and yellows, but the blue or green lights gave the lake with the protruding dead tree trunks a magical yet eerie quality. Visitors brought their cameras and tripods, each trying to capture the essence of it.

Camping in Winter

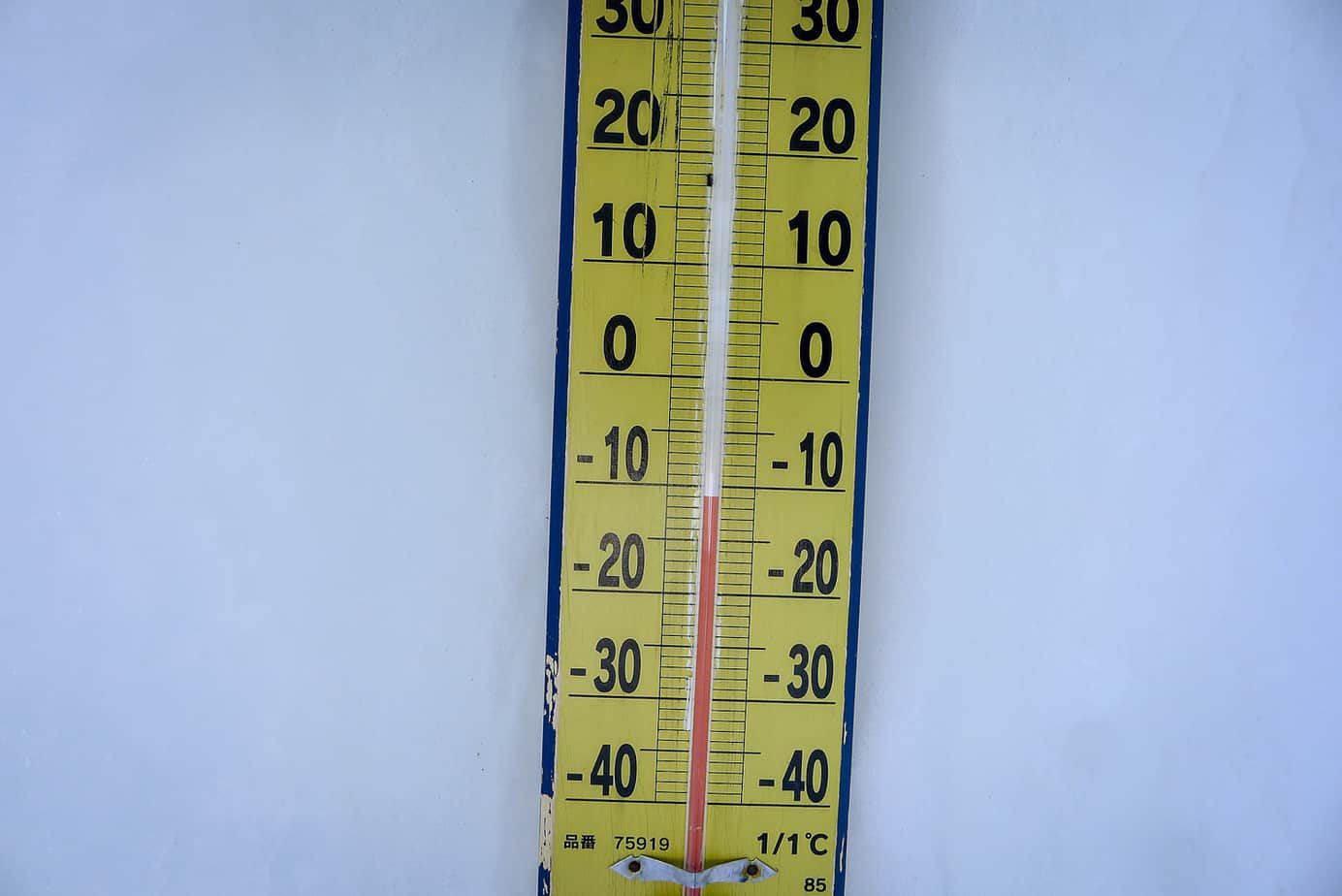

Due to the snow, camping was limited to staying in cleared parking lots. When we got up—in this cold never before 8 a.m.—a layer of ice covered the inside of the bodywork’s metal parts and car windows. In these temperatures, food kept outside the fridge such as fruit and vegetables froze and bananas turned pitch black. I had therefore switched systems: food that normally goes in the fridge stayed out, and fruits and veggies were kept in the fridge—obviously turned-off—to prevent their freezing.

Despite the temperatures dipping into the 10s (F), we slept well, warm under a down blanket with an additional down sleeping bag and wearing our thermal underwear. As always, we kept one window open for fresh air. The tough part was throwing off those blankets in the morning, getting dressed, and getting the small heater started that we had bought for this winter adventure. It ran on a gas canister that needed to be warm before it worked. I put the canister in bed before getting up, which helped.

Snowstorm

We cooked inside with the Coleman stove on one of the benches, drank our ginger tea and ate oatmeal while the heat de-iced the car windows. Another walk got our bodies working properly again, and we hit the road once more, driving south. “Icy road,” the LCD screens over the road warned us. They also gave weather predictions for snow and rain. Sometimes the roads had red arrows over them, which we initially didn’t understand. Until, one evening, we neared Rausu on the far northeastern corner and got caught in a snowstorm. Along the coast and with the wind blowing in from the ocean we were totally unprotected as the snow cut across the windshield, blurring our view, while gusts shook the Land Cruiser like a feather. Within minutes the world was so white, we could no longer distinguish between the road, hard shoulder, pavement, and fields along them. Here the red arrows came in, which now fiercely blinked, indicating exactly where our lane ran, preventing us from crashing into god knows what.

Igloo Lake

But this morning, there was no such weather. Instead, a blue sky with the sunshine glistened on surfaces. Somewhere along the way we had spotted a poster of a hot spring amidst a frozen lake, and today we were on our way to find it. We crossed a flat terrain where the road had temporary wind deflectors on one side to protect vehicles from snowstorms that came in from the side. The weather changed: blue sky, snow flurries filling the air, snowing hard, snowstorm.

By the time we had climbed to 3,000 feet over an icy road that stopped in a settlement, blue was back. The village lived off tourism, the few buildings being hotels, restaurants, coffee shops and the like. They looked out over a vast, frozen lake hemmed in by mountains—a fairytale view.

Amidst the lake stood igloos. One of them was a large bar-cum-coffeeshop, so big that the roof was supported by ice columns. It had secluded corners with benches of ice. At the ice bar you could buy drinks in glasses made of ice. The igloo next to it was more a cylindrical wall without a roof. When lying on its benches in darkness at night to watch the stars, the walls protected us against the fierce wind that tore across the lake. The last igloo was a chapel, set up for newlyweds to have their pictures taken. In a way, it was all terribly touristy, yet we liked it, maybe because we had the place pretty much to ourselves.

We had come for the onsen, the hot bath. Most onsens are separated by gender and you go nude, but the ones in the wilderness are often mixed and if you want you can wear a bathing suit. We undressed, put in one toe and then another toe to give our bodies time to adjust to the scalding heat. Little by little, we sank deeper into the water that was dark red/brown from iron and other minerals. The bath was protected on three sides by a wall of ice, the fourth side open to the frozen lake. On our arms, we leaned on the edge of the bath to take in the mind-blowing view. For a moment we had landed in paradise.