Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal, Fall 2015.

El Camino del Diablo translates to The Road of the Devil. The name itself evokes an eerie feeling of discomfort, and it should. Over the last 1,000 years this barren track has earned its name with soaring temperatures, waterless expanses, and an ever-rising death toll. It comes from humble beginnings as a Native American footpath, but earned its infamy with the Spanish in 1540. During his march from Mexico to the fabled cities of gold, conquistador Francisco Vázquez de Coronado dispatched a small expeditionary force to seek out a rumored river junction to the north. Although the expedition did return, the immense hardship encountered during their journey led the soldiers to name the path after the Devil himself.

Over a century later, a Jesuit priest named Eusebio Kino retraced the route, this time mapping the water sources and punching through to the Pacific. Unknowingly, Kino paved the way for over 300 years of travelers to follow, including immigrants, gold seekers, smugglers, and more recently, four-wheel drive enthusiasts.

General Information

Today the route remains largely unchanged. With a complete absence of resources and emergency services, it is only suitable for high-clearance four-wheel drive vehicles carrying their own water, food, and supplies. In other words, all visitors must use the trail at their own risk. The road is contained within three separate areas of land management, each of which shares a border with Mexico. Jurisdictions include Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in the east, Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge in the center, and the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range in the west. Together these segments comprise one of the largest and best-preserved sections of the Sonoran Desert north of the border.

Flora is more diverse here than in most U.S. deserts, and includes species of agave, cactus, legume, and palm to name a few. Most notably, the Saguaro cactus can be seen thriving throughout the landscape; the Sonoran is the only place where they grow naturally. The desert climate is also well-suited to many types of fauna: bobcat, coyote, fox, rabbit, javelina, ringtail cat, mule deer, and several types of desert rat all make their home here. Bird species include hummingbird, wren, owl, hawk, quail, and dove. If you are looking for reptiles you may find rattlesnakes, Gila monsters, and even tortoises.

Flora is more diverse here than in most U.S. deserts, and includes species of agave, cactus, legume, and palm to name a few. Most notably, the Saguaro cactus can be seen thriving throughout the landscape; the Sonoran is the only place where they grow naturally. The desert climate is also well-suited to many types of fauna: bobcat, coyote, fox, rabbit, javelina, ringtail cat, mule deer, and several types of desert rat all make their home here. Bird species include hummingbird, wren, owl, hawk, quail, and dove. If you are looking for reptiles you may find rattlesnakes, Gila monsters, and even tortoises.

The Drive

The Drive

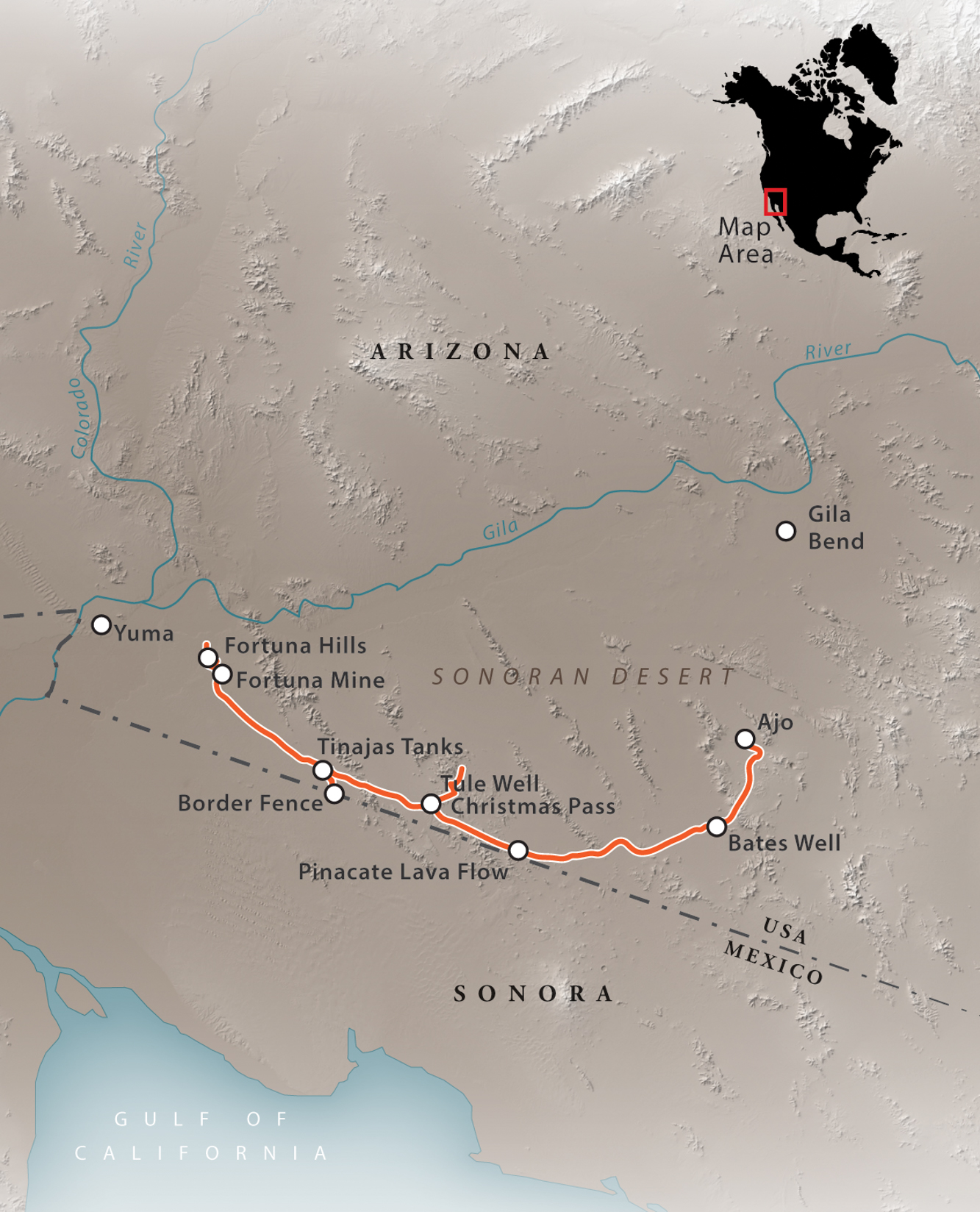

El Camino del Diablo bisects some of the most beautiful and remote Sonoran Desert in the U.S. However, it also runs along the Mexican border, adjacent to active bombing ranges, and across terrain so rugged and scorched that it has claimed up to 2,000 lives from thirst alone. Due to these dangers, your trip won’t start on the dirt, but in a government office navigating a litany of warnings and paperwork depicting various ways to meet one’s untimely demise. We won’t go into all the specifics, but the gist of it is that if you break down, die of thirst, are killed by smugglers, bitten by snakes, crushed in a mine, shot, or blown up by a bomb, it’s not the government’s fault. You can read the exact, and rather shocking word, in the story “On the Devil’s Doorstep” HERE.

After spending a morning cutting bureaucratic tape, you’ll find yourself rolling into the town of Ajo, Arizona, 40 miles north of the border. There to greet you is an inviting symphony of sights, sounds, and smells, each in stark contrast to the barren wasteland that lies beyond. Beautiful bleached white churches stand on the west side of the square, as if on display for the Curley School for artists, which dominates the backdrop. The air is sweet with the smell of flowers in the courtyard, coffee brewing at the local shops, and the sound of wind blowing through the palm trees. This charming town is the perfect opportunity to stop, enjoy the moment, and let those thoughts of guns and explosions drift off to the far back of your mind. Once you’ve had your fill, cruise three miles south and take Darby Well Road to Bates Well Road. This will deliver you straight into El Camino del Diablo.

After spending a morning cutting bureaucratic tape, you’ll find yourself rolling into the town of Ajo, Arizona, 40 miles north of the border. There to greet you is an inviting symphony of sights, sounds, and smells, each in stark contrast to the barren wasteland that lies beyond. Beautiful bleached white churches stand on the west side of the square, as if on display for the Curley School for artists, which dominates the backdrop. The air is sweet with the smell of flowers in the courtyard, coffee brewing at the local shops, and the sound of wind blowing through the palm trees. This charming town is the perfect opportunity to stop, enjoy the moment, and let those thoughts of guns and explosions drift off to the far back of your mind. Once you’ve had your fill, cruise three miles south and take Darby Well Road to Bates Well Road. This will deliver you straight into El Camino del Diablo.

Upon leaving Ajo, it doesn’t take long to realize why this track earned the title of the Devil’s road. As you roll over hills and through washes, the colors of town begin fading to brown, and life slowly shrinks back from the parched landscape. The driving surface, which has been largely improved by the Border Patrol, appears wide and smooth, but can be deceiving. Daily traffic from increased control efforts has formed a bone-rattling track of corrugations, some of which are so harsh we had to slow to a crawl to prevent suffering the fate of previous passersby, whose bolts and loose parts now litter the area.

Upon leaving Ajo, it doesn’t take long to realize why this track earned the title of the Devil’s road. As you roll over hills and through washes, the colors of town begin fading to brown, and life slowly shrinks back from the parched landscape. The driving surface, which has been largely improved by the Border Patrol, appears wide and smooth, but can be deceiving. Daily traffic from increased control efforts has formed a bone-rattling track of corrugations, some of which are so harsh we had to slow to a crawl to prevent suffering the fate of previous passersby, whose bolts and loose parts now litter the area.

One of the fascinating elements of this road is witnessing the history of man’s victories and defeats as they unfold before you. Homesteads like Bates Well and Tule Well stand as markers where, despite adversity, families dug in and made a life in the Sonoran. Their homes, though deteriorating, remain open; they are much the same today as they were 100 years ago. The Tinajas Altas or High Tanks—depressions in the stone created by eons of wind and water erosion—exist as another place of hope. Although more difficult to find, a little persistence and some climbing will bring you to the very watering holes that saved countless lives from dehydration, making this route possible for so many immigrants.

One of the fascinating elements of this road is witnessing the history of man’s victories and defeats as they unfold before you. Homesteads like Bates Well and Tule Well stand as markers where, despite adversity, families dug in and made a life in the Sonoran. Their homes, though deteriorating, remain open; they are much the same today as they were 100 years ago. The Tinajas Altas or High Tanks—depressions in the stone created by eons of wind and water erosion—exist as another place of hope. Although more difficult to find, a little persistence and some climbing will bring you to the very watering holes that saved countless lives from dehydration, making this route possible for so many immigrants.

Of course, many tales did not end happily. Grim reminders of every sort, from crosses to whiskey bottles, mark the resting places of migrants who lost along the route. It seems that for every story of life and success, there were two or more of death and defeat. Hundreds of tales, along with the souls who bore them, simply vanished into the desert, never to be told.

It seems appropriate that in a place so adept at taking life, we would test weapons designed to do the same. El Camino del Diablo is largely surrounded by the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range, in which the Air Force’s best pit their skills against one another in dogfights and drop air-to-ground ordinance on unsuspecting cacti. As seen from the road, these aerial ballets are nothing short of stunning, and their seemingly silent progression can quickly lull even the most uninterested traveler into observing with a false sense of serenity. For us, the illusion was shattered by the concussion of a distant bomb, which impacted our chests with a dull but heavy thud.

It seems appropriate that in a place so adept at taking life, we would test weapons designed to do the same. El Camino del Diablo is largely surrounded by the Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range, in which the Air Force’s best pit their skills against one another in dogfights and drop air-to-ground ordinance on unsuspecting cacti. As seen from the road, these aerial ballets are nothing short of stunning, and their seemingly silent progression can quickly lull even the most uninterested traveler into observing with a false sense of serenity. For us, the illusion was shattered by the concussion of a distant bomb, which impacted our chests with a dull but heavy thud.

As you pass through the western section of the Goldwater Range, a foreboding sign, complete with skull and crossbones, welcomes you to the Fortuna Mine. Upon first glance, the area can appear uninteresting. A closer look reveals crumbling buildings, towering water storage tanks, and hidden powder holds. Take the time to explore and you are sure to be rewarded.

As you pass through the western section of the Goldwater Range, a foreboding sign, complete with skull and crossbones, welcomes you to the Fortuna Mine. Upon first glance, the area can appear uninteresting. A closer look reveals crumbling buildings, towering water storage tanks, and hidden powder holds. Take the time to explore and you are sure to be rewarded.

After the mines, drivers are treated to one last delight. The road arcs up onto the spines of a series of hills, rapidly rising and falling as if on the back of a serpent. The path is smooth and grants one last view before diving back into the desert with an abrupt descent. From here, a few miles will bring you back to the pavement of Fortuna Foothills Arizona, where El Camino del Diablo reaches its merciful end.

For the full adventure story including dust, bombs, and immigrants in the night, check out On the Devil’s Doorstep here.

Access

Access

West entrance: From Fortuna Foothills, Arizona, take the S. Ave. 13E/S. Foothills Blvd. exit. Drive south for three miles to E. County 14th Street, and turn left. Continue for two miles, and turn right on a dirt road marked by a Barry M. Goldwater Western Range sign.

East entrance: From Ajo, Arizona, head south 2.5 miles on SR 85, turning right on Darby Well Road. Continue past Bates Well and you will reach El Camino del Diablo.

Logistics

Distance off-pavement: 148 miles

Suggested time: 2-3 days

Longest Distance without fuel: 155

Fuel Sources

Ajo, Arizona 32°23’35.2″N 112°52’21.4″W

Fortuna Foothills, Arizona 32°38’30.3″N 114°24’36.9″W

Difficulty

Most of El Camino del Diablo is easy to traverse. However, its remote nature combined with a few challenging obstacles and navigational difficulty gives it a rating of moderate.

When to Go

The Sonoran Desert has a fairly stable climate and is pleasant to visit for most of the year. We recommend avoiding the trail from mid-May to mid-September due to high summer temperatures and monsoon rains.

Permits and Fees

The Barry M. Goldwater Air Force Range and Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge are covered under one permit, which can be acquired at the Luke Air Force Base Range Management Office * see editor’s note, below* or the BLM’s Yuma or Phoenix field offices. Permits are free but require you to watch a video and sign several liability waivers. NOTE: Every individual must visit the office and acquire a permit. Permits are not issued on a per vehicle basis.

The permit for Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument may be acquired at the Kris Eggle Visitor Center or at the kiosk located directly along the route. The fee is $8/vehicle, $4/bicycle (7 Days), or $20 for an annual pass.

* Editor’s Note 2/9/2021: It has been brought to our attention that the BLM has not issued these permits since 2001. The permits are handled by the military only. At this time, the permitting process is housed on the Luke Air Force Base website which can be found here: https://luke.

Suggested Campsites

Bates Well

Accommodates 3-4 vehicles

Historic buildings

32°10’11.84″N, 112°57’5.76″W

Last Resort

Accommodates large groups

Picnic tables and grills

32°5’55.98″N, 113°17’1.43″W

Devil’s Doorstep

Accommodates 3-4 vehicles

Scenic overlook

32°7’27.57″N, 113°32’50.29″W

Tule Well

Accommodates large groups

Picnic tables and grills, historic buildings

32°13’34.35″N, 113°44’58.85″W

Crater Camp

Accommodates large groups

Fire ring, wide open space, old bomb crater

32°15’14.08″N, 113°41’2.59″W

Sheltered Pass

Accommodates 1-2 vehicles

Secluded

32°16’37.28″N, 113°41’39.03″W

Christmas Pass

Accommodates 3-4 vehicles

Scenic overlook

32°16’39.12″N, 113°41’32.72″W

Border’s Edge

Accommodates 1-2 vehicles

32°17’42.89″N, 114°2’34.55″W

Tinajas Altas

Accommodates large groups

Historic site

32°18’44.63″N, 114°2’50.76″W

Contacts

Marine Corps Air Station, Yuma, Range Management Office, 520-341-3402

Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge fws.gov/refuge/cabeza_prieta/, 520-387-6483

BLM Yuma Field Office blm.gov/az/st/en.html, 928-317-3200

BLM Phoenix Field Office blm.gov/az/st/en.html, 623-580-5500

Yuma Regional Medical Center yumaregional.org, 928-336-2000

Yuma Police yumaaz.gov/police/, 928-373-4700

Border Control, Yuma, 928-341-6500

Resources

Maps and general information are provided for free when acquiring permits, and we recommend bringing a DeLorme Arizona Atlas & Gazetteer as a backup. Our team’s GPS track can be found by visiting the overland routes home page here.

Notes

Overland Route descriptions are intended to be an overview of the trail rather than turn-by-turn instructions. We suggest you download the Hema Explorer app and Cloud GPS track, as well as source detailed paper maps as an analog backup. As with any remote travel, conditions can change dramatically. In summer, rains can subject desert dry washes to flash flooding.

While many travel warnings dispatched by the government can be a tad overzealous, the dangers of this route are very real, and warnings should be weighed carefully. Encountering unexploded ordinance and military activity is rare, but it is very likely you will cross paths with illegal immigrants or smugglers in various degrees of desperation. If you are uncomfortable with this sort of encounter, we recommend traveling in groups or choosing a different route.