Photography courtesy of An African Abroad by Olabisi Ajala

Arriving at the Mandelbaum Gate border post between Israel and Jordan’s Jerusalem, Nigerian journalist Olabisi Ajala spotted a sign on his right that read: “This is Jordan. Beyond is no-man’s-land. Only U.N. officials allowed.” Guards and soldiers from both nations watched from high towers, bombed-out buildings, and from behind piled sandbags and swiveling machine guns. A narrow pathway caught Ajala’s eye. It was just wide enough to squeeze a scooter through at top speed.

Clamping his right hand on the throttle, Ajala raced forward, steering toward no-man’s-land and across to the Israeli post. Arab guards shouted, “Come back, or we will shoot you! Come back here!” A single bullet burst Ajala’s rear scooter tire, causing him to crash through the Israeli post, landing on his back and puncturing the fuel tank. An Israeli border guard, along with a few gun-toting soldiers, ran toward him with a stretcher. The following Monday, Ajala found himself in Israel’s Foreign Ministry, enjoying a cup of tea with the chief of the Afro-Asian Department. Whether he was arrested, imprisoned, or deported, Ajala always seemed to land on his feet.

“My Lebanese captors on the Israeli-Arab frontier.” – Olabisi Ajala, An African Abroad

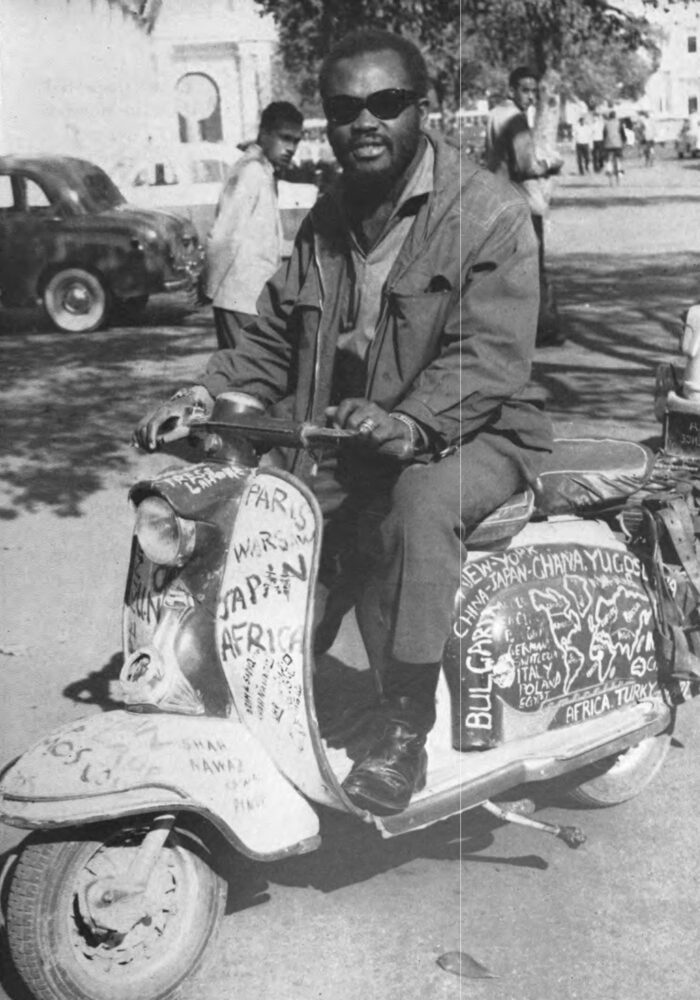

Born in Ghana, 26-year-old Olabisi Ajala developed a reputation for whizzing through perilous border crossings on his Lambretta scooter, a deluge of bullets and shouting guards following in his wake. Between 1957 and 1962, Ajala journeyed across 87 countries on his scooter, touring across North America, Eastern, and Western Europe, through Africa and Asia, and as far east as Korea, Indonesia, and Australia.

The purpose of his travels, which he divulged in his book An African Abroad, was to comment on diverse cultures and “to unfold before the eyes of the reader the characters of a few of the leaders and to share my conversations and my observations on their mentality.” His strong will and unorthodox methods led to one-on-one interviews with many world leaders of the time, including Nikita Krushchev of the Soviet Union, Gamal Abdul Nasser of the United Arab Republic, Pandit Nehru of India, and the Shah of Iran.

“I have met with brutality and racial intolerance,” Ajala wrote. “I have felt the bitter evil of Man’s inhumanity to Man and have marvelled at the goodness of the humane-hearted. I have seen the iron hand of military, autocratic and monarchical dictatorships grinding down on less fortunate peoples. Most important of all, I have seen the practical sides—good and bad—of both democracy and communism.”

Making friends with the Red Army.

Ajala attended the Baptist Academy in Lagos and the Ibadan Boys’ High School in Ibadan as a child. At 18, he moved to the United States (“with the blessing of my mother and against the wishes of my father”) as a pre-med student at the University of Chicago. He later studied at Chicago’s Roosevelt College and Columbia University in New York City. Ajala’s international scooter trip wasn’t his first overland venture. From June 12 to July 10, 1952, he cycled 2,280 miles across the United States, delivering a series of lectures on “Present Day Africa.”

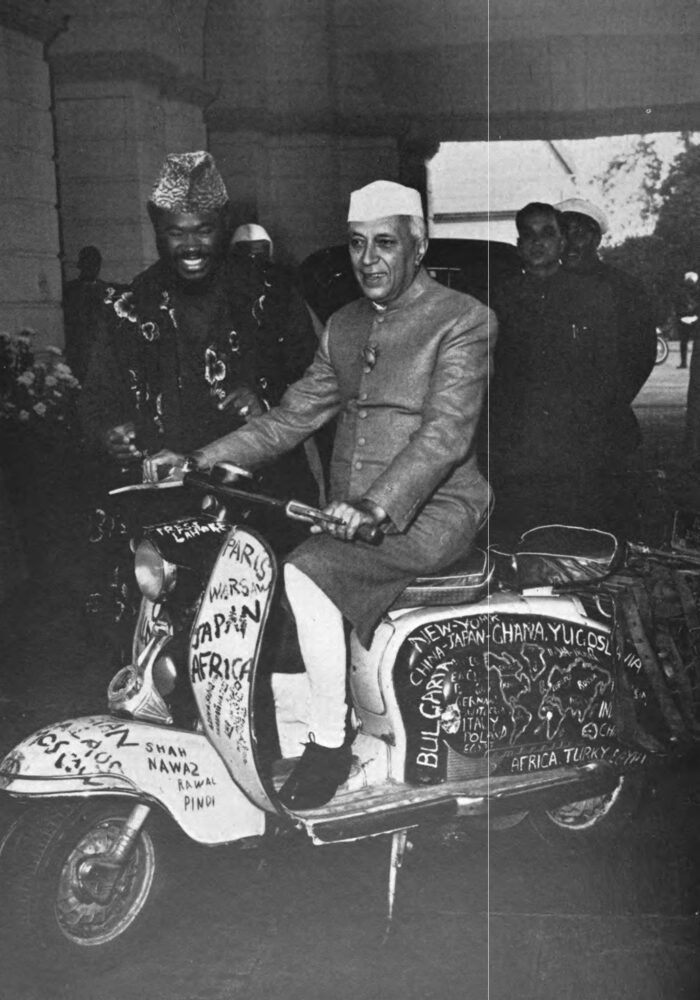

The first destination that Ajala discusses in An African Abroad is India. He found it refreshingly straightforward to request an interview with Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, who was India’s prime minister at the time. After contacting the appointment secretary (who was also the chief of intelligence and security), a meeting was arranged within 24 hours. “Face to face with him, I felt that he was unselfconsciously shy, timid, and unusually moody. He has a cautious personality and impressed me as a man of honesty, a man very conscious of Man’s psychological dilemma,” Ajala wrote. At the end of their meeting, Nehru asked to have a seat on Ajala’s scooter. “I would very much like to sit on it myself, that is if it will not take off on its own, with me on it… I wish I were in a position to travel like you. There is so much to see and know about people in other parts of the world.”

While in India, Ajala covered 6,500 miles on his motor scooter, through Amritsar, Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, and through many towns and remote villages. “Strange though it may sound,” he wrote, “most of the kind and understanding attention I received in India was from people inhabiting remote villages and farms. These farmers, villagers, and peasants could hardly understand my language, yet they were able to appreciate the common fact of human dilemma and necessity. Much as I hate to admit it, in India, I was subjected to humiliation and embarrassment because of my color [and] on a number of occasions denied admission to social clubs and public restaurants…”

In East Berlin, Ajala broke through a throng of Russian M.K.V.D. Security Police, attempting to approach Premier Khrushchev for a visa to enter the Soviet Union. Ajala decided to personally hand a letter to the Soviet leader, scrambling through the cordon to face him. “I watched him duck and take protective cover behind his entourage,” Ajala wrote. “No doubt Khrushchev thought that I was a hired assassin who was out gunning for him.” The two smiled, shook hands, and two days later, Khrushchev granted Ajala a one-month visa. Later, at the German-Polish border, Ajala was apprehended and charged with espionage. He spent five days in a dark 8- by 3-foot cell. When Prime Minister Khrushchev heard of the detention, he gave orders for Ajala to be released immediately.

“Greetings to Khrushchev.” – Olabisi Ajala, An African Abroad

In Iran, Ajala traveled 950 miles from Maku to Tehran, over rough, bumpy, and stone-filled roads. “Quite a number of times, I had to struggle and plough my way through the unpaved and rugged road in order to…get a vague idea of my direction. To trust in the international road map I had with me for guidance was useless.” In the outskirts of Tehran, Ajala told of the “odor of dirt and filth,” while the city centre boasted modern American goods, from television sets to colourful dresses, and beautifully styled balconies encircling skyscrapers and apartment buildings. “Despite its slow but sure progress,” he wrote, “Iran is ridden with abject poverty, and the slums of Tehran, a city inhabited by more than 1,000,000 people, can compete with those of Calcutta.”

Back to his old tricks, Ajala had several “ghastly experiences” at the hands of the Iranian shah’s bodyguards. “[They] beat me up a number of times and smashed my cameras, in the process of my unsuccessful efforts to break through the cordons in order to reach the Shah.” Eventually, Ajala gained access to the shah through diplomatic protocols involving a deluge of ministries. Dressed in a dark-gray-striped suit, white shirt, and white-dotted black tie, the shah spoke flawless English and, according to Ajala, appeared interested in the welfare and progress of newly independent African countries. “From what I saw during the three months I spent in Iran, Ajala wrote, “the Shah seemed to be at the lowest ebb of popularity among his people. Like any other man, [he] is subject to joy and sorrow, success and failure. What endeared him to me was the fact that he did not attempt to hide this fact from me.”

“I meet the Shah of Iran” – Olabisi Ajala, An African Abroad

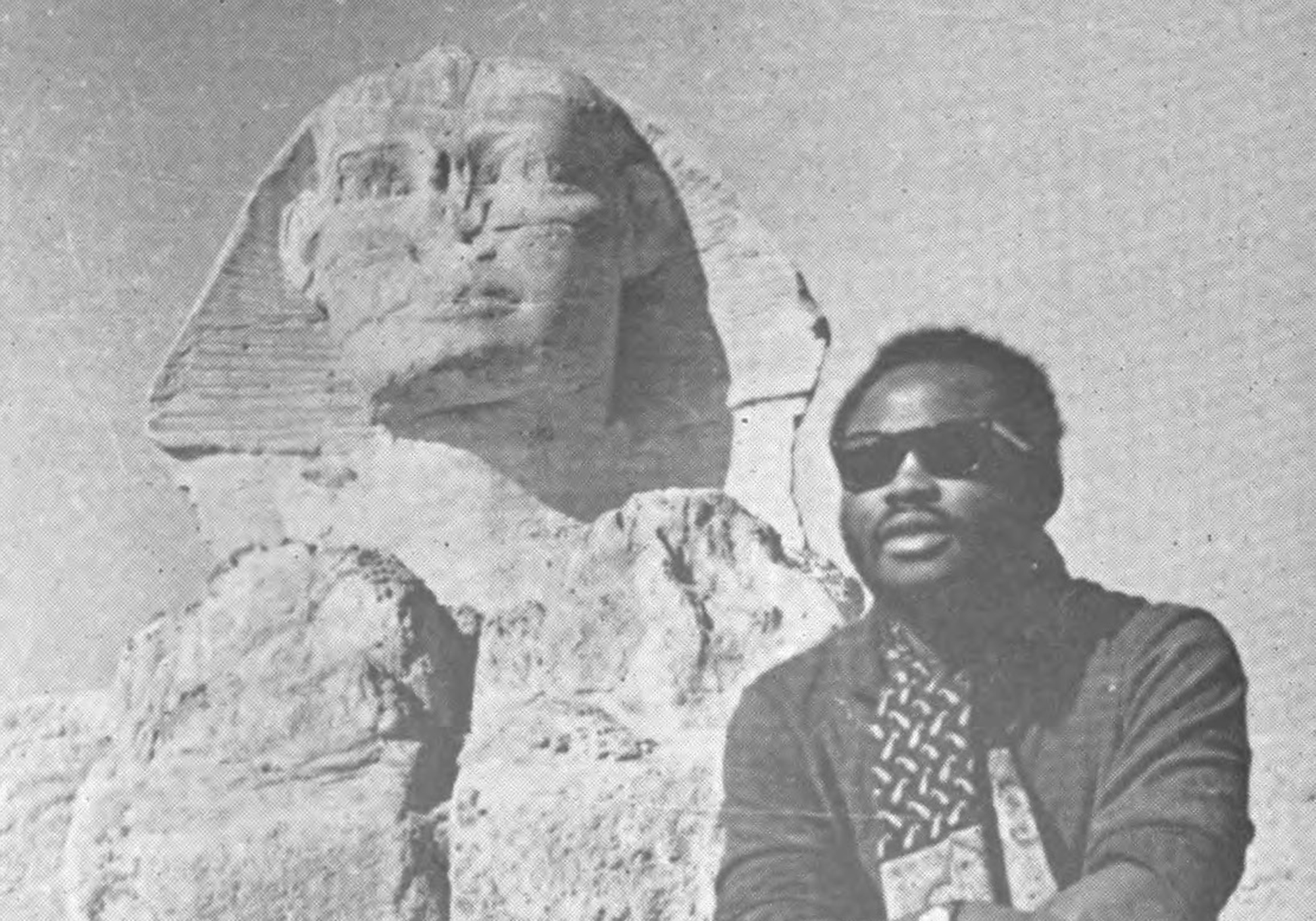

Ajala spent 13 months in the Middle East, including touring through Jordan, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, and Israel. While he gained exclusive interviews with the Premier of Jordan, Hazan Majali, President Nasser, and Prime Minister Abdul Karim Kassem of Iraq, Ajala was arrested, imprisoned, and deported on three different occasions. This did not seem to weaken his resolve, however. Every day for two weeks, Ajala waited in front of the presidential palace in Damascus for Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. On the thirteenth day, Nasser emerged from his residence. “I was in my flowing Nigerian agbada dress and made sure that I was conspicuous,” Ajala wrote. “Over the steel rails of the gate… I shouted as loudly as I could: ‘President Nasser, I am an African visitor here. I have a complaint against Cairo police. I seek your permission to talk to you.’” President Nasser agreed, asking Ajala to return the next day at three o’clock.

According to Ajala, Nasser’s fame and popularity were at their height during his visit. Nasser’s photograph was prominently displayed in expensive gold-rimmed frames nearly everywhere, including in shops, houses, street corners, buses, and government offices. “To anyone who has not had the chance of meeting Nasser and of talking with him,” Ajala wrote, “he might appear a terror, a fanatical nationalist, and a dictator of the worst type. All these opinions would be presumptuous and far from correct.” The two frankly discussed political topics of the day, including Nasser’s struggle for Arab unity, his thoughts on Israel, and African nationalism. His final words to Ajala were “encouraging” and, according to Ajala, appeared to be weighted with his beliefs: “In the United Arab Republic, as it ought to be, each human being is equal, irrespective of his colour, race, and religion.”

“Nasser was cordial.” – Olabisi Ajala, An African Abroad

Olabisi Ajala died in Lagos on February 2, 1999, at the age of 70. But his words live on, not only in An African Abroad but in his name. The phrase ajala is now used to define the term “traveller” in Nigeria. Ajala’s book is currently out of print, but those interested can access the digital version via the HathiTrust Digital Library.

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to make sure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.