It was about 11 P.M., and I had just finished brushing my teeth on the wooden catwalk of the Garver Mountain Fire Lookout, 40 feet off the ground. I had bikepacked to the lookout that afternoon from the bustling six-business metropolis of Yaak in northwestern Montana. After brushing, I spent a few minutes studying the sky. The stars were thick and crowded the night air. Big Dipper, Little Dipper, Andromeda, Cassiopeia—they were all there. The Milky Way was a frothy band spilling downward to the southwest.

An off-white, low-arcing rainbow sat just above the horizon to the north, far past the Canadian Rockies whose silhouette looked like a string of tiny flat black triangles against the light blue sky. The arc stretched across most of the northern horizon. It was distinct, not like the lights cast from a city in the distance. (Besides, I was in the very northwestern corner of Montana, a stone’s throw from the Idaho panhandle, and there’s nothing out there for hundreds of miles. Nothing.) The white glowing rainbow was odd, like nothing I’d ever seen.

“Surely that can’t be…” I thought.

My heart skipped a beat when I was realized I was staring at the Northern Lights, a scientific wonder on my bucket list. I didn’t have an immediate plan to see the Aurora Borealis, and it wasn’t even on my radar for this trip. Despite not being the brilliant green we see in photos, the sight brought tears to my eyes. After days of stressing about my bike fit, my fitness, my lack of experience bikepacking, and the 100-some-odd fires burning in the Kootenai National Forest, I felt some peace.

I like nature that way. It can fix things. I’d been yearning to spend time up high in the Colorado Rockies, camp above treeline, take a break from the static that comes with being a mother, an editor, a wife, dog-owner, car-owner, house-owner, volunteer, community member, library card-holder…and this bikepacking trip in Big Sky Country—even if the big sky was a bit smoky—put things back into perspective. Spending each day with only a small supply of clothes, food and water on your back and bike can do that.

I had two companions, Laura and Kelly, and we traveled by map and compass, pre-printed route suggestions from The Google, and Garmin waypoints. It was mid-August, and we based out of Yaak, 120 miles north of Kalispell, Montana, “The Yaak,” as it is known by locals and visitors, is not so much a town of 240 people but an “area” that locals proudly define by mile markers and highways. You can’t claim to be from The Yaak, if you’re just outside those mile markers. (But if you’re from The Yaak and need furniture delivered, you’d better fudge on those mile markers, otherwise the driver won’t make the journey north on the narrow South Fork Road/NF-68, which in spots looks more like a wide bike path than a road.)

Our tour covered approximately 170 miles in four days, with three fire lookouts as our nightly destinations. (A fourth night of open-air camping was scheduled but we skipped it, opting to pedal 61 miles back to our start-stop location in The Yaak, a Kootenai Indian word that means “arrow.”) Travel to each of the lookouts was via Forest Service roads and singletrack, but we pedaled paved highways and chip-seal roads as well. I likened the riding each day to the mountain biking in Santa Cruz, California, where you almost always end on an uphill. The lookouts—for obvious reasons—are on the very tops of the peaks, and our three destinations were located on some of the highest points in the Purcell and Salish mountain ranges: Garver Mountain at 5,784 feet, Big Creek Baldy at 5,768, and McGuire Mountain at 6,970 feet.

From the lookout, the rounded mountains seem to roll forever, blanketed by giant western red cedar, ponderosa, lodgepole pine, and a great variety of other evergreens. The Kootenai National Forest is named for the Kootenai Indians who formerly occupied the region and still retain treaty rights. The forest is Montana’s premier timber-producing forest, and spots of lighter-colored young trees among the older growth make up a patchwork of greens on the hillsides—one or two patches of brown show the zones that were most recently harvested.

A garden of tall, skinny cairns sits among a craggy spot to the south of the lookout, along with a slightly unkempt outhouse and a boarded-up cabin to the west. The 1/4-mile access trail full of roots and rocks drops to the north. The mountaintop is small and rocky, which brings on a strong feel of vertigo from the lookout deck, but the first evening is smoke-free and clear. We are north of the fires and can see the Canadian Rockies and the peaks of Glacier National Park.

The lookout is equipped with a woodstove, two platforms with mattresses for sleeping, a desk, and some shelving. Previous campers have also left two folding camp chairs, a headlamp, a mirror, dried goods (such as oatmeal, which I enjoy the next morning), and water. It’s pretty comfortable, and with glass windows running the length of each wall, the views are 360 degrees.

Each fire lookout still has the remnants of an Osborn Firefinder. The firefinder is a round metal table about 30 inches across that sits on an adjustable pedestal in the center of the room. It has a map, a sight and crosshairs, and a tape measure by which to locate an object (such as a forest fire) and calculate compass headings.

On our first night, we can see smoke plumes to the west and east, and flames to the southwest on a faraway ridge. The Garver Mountain logbook contains an entry by Scottie, Caleb, and Keith Mack (three generations of Macks), who stayed in the lookout the night before. After their steak dinner, they reflected on their hike and the fires: “We also talked about the fire which was burning on Teepee Mountain which was next to my dad’s house. We could see the fire balls from the lookout.”

As the wind kicks up, the Teepee Mountain flames expand and contract. It doesn’t make sleeping any easier.

We get rolling at about 9:30 A.M. The payoff to ending each day with a big climb is the descent the following morning, and today we rally down a gravel road to the Yaak River Valley. It’s hardly any work at all as we cruise onto the main drag of The Yaak, where the mercantile is hopping with motorcyclists, RV tourists, and a few locals—half of whom are transplants from Colorado.

Everyone’s chatty, and one woman tells me: “You haven’t lived till you’ve seen The Yaak.”

The bulletin board outside the mercantile has a flier with fire updates. The fire ban is being upgraded to Stage 2, but there are no new closures.

The second part of today’s route consists of the Yaak summit south of town, some mellow road stretches, and a 6-mile climb up a combination of Forest Service roads to the lookout. The final climb is too steep to pedal in one push, but the early-evening temperatures and shaded corridor of giant cedar and lodgepole pine make it bearable. The top of the road is 4×4 with some chickenheads and loose dirt. It leads straight to the Big Creek Baldylookout. I’m tired, and the 50 steps that zig and zag to the top of the lookout are formidable.

A firefinder sits in the center of this lookout, too, and it has a propane stove and two lantern-style lights mounted on the walls. Above the windows are a color photo of the lookout, its history, a small U.S. flag, a sketch of a chipmunk by a 13-year-old, and a sign with the words “Montana, the Last Great Place.”

The wind picks up again and I have trouble falling asleep, worried about the fires and smoke but also driven nuts by the howling wind.

It’s windy when we wake, and I can’t tell if it’s overcame or smokey. There’s ash on the bikes, and we are all concerned about the air quality. As we prepare breakfast, we agree to do all it takes to get more fire information, as well as locate a water supply, but Kelly’s current focus is boiling water.

“At least we have coffee. Everything else is just ‘phzsh, phzsh, phzsh,’” she says, whipping her hands back and forth alongside her ears.

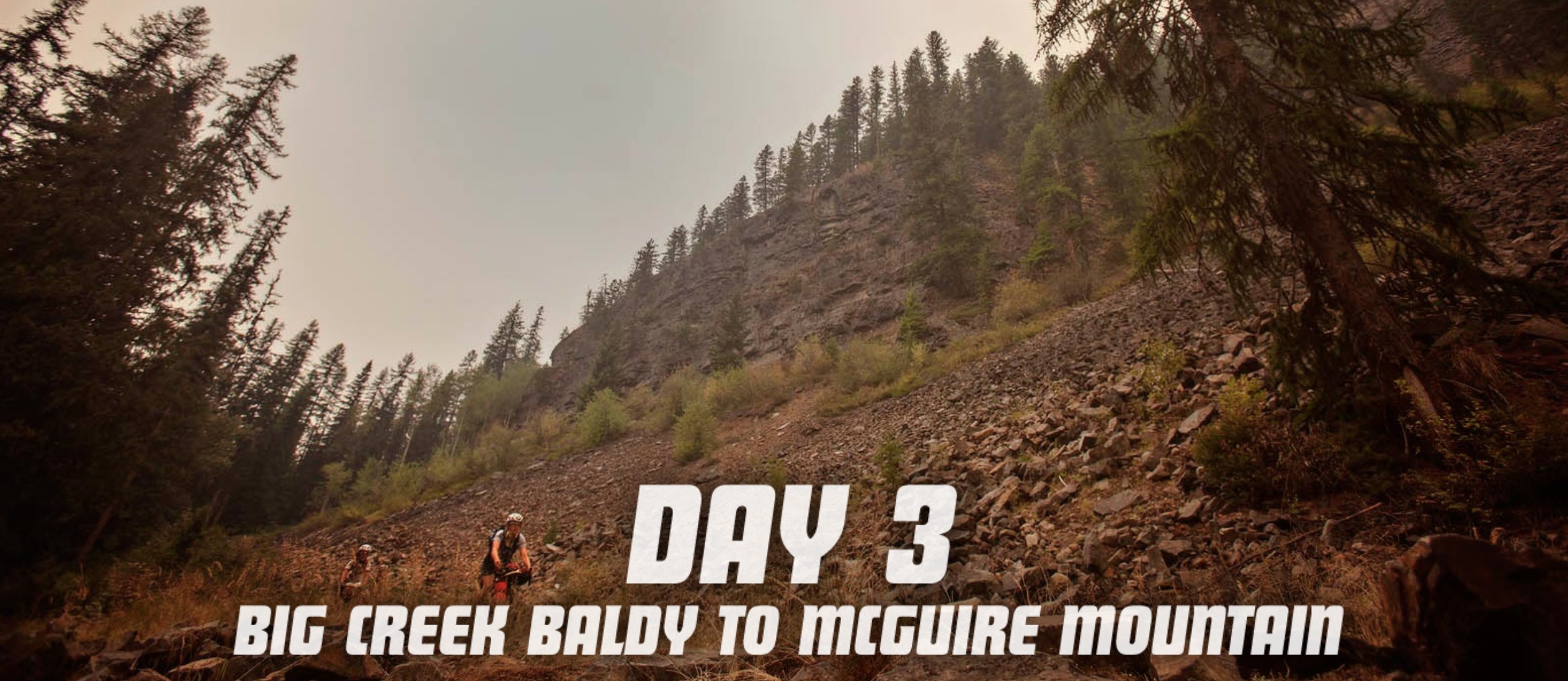

We begin the ritual of reviewing our route, and Kelly proposes taking a different road than planned. The map shows a doubletrack that will save some miles and some climbing. I’m all for it. We get started pedaling and skirt below cliffs and a few rockslides as we make our way down the Big Creek drainage.

This portion of Montana is lush due to its Pacific maritime climate and has a huge variety of coniferous trees. The drooping branches and soft bristles of cedar and hemlock contrast the lodgepole pine, and Engelmann spruce. Black tree lichen (or “bear hair”) clings generously to the branches and peppers the dirt roads. The descent is my favorite part of the day.

Today’s route also includes some miles of road on both the east and west sides of the 90-mile-long Lake Koocanusa (a combination of the words Kootenai, Canada and USA). The paved road along the lake is a popular motorcycle tour, but there’s hardly any traffic and there’s not a single boat on the water or person on the shore. It feels abandoned. The mountains appear flat and disconnected from the earth. The wind skims across the water, creating small whitecaps that look like the fins of a Loch Ness monster swimming just below the surface. The wind races along the guardrails of the 1/2-mile-long Koocanusa Bridge, composing a hollow, high-pitched, metallic drone. I imagine aliens landing at any moment.

The least favorite part of the day is the 3.6-mile hike in to McGuire Mountain Lookout. After knocking out the bulk of the climb to the top, we ride past one trailhead sign that shows an icon of two hikers and an arrow with the words “McGuire L.O. 2.5 mi.”, in search of our more “cycling-friendly” route on the opposite side of the mountain.

When we can’t locate the second trailhead, we turn around and pedal back to the first sign. It’s 7 p.m. The trail begins as a perfect hiking trail, gently winding up and over stretches of a cream-colored, shale-type rock and past an old quarry before entering a forested area with ferns and short bright grasses. It’s rideable in spots, but has some steep pitches and downed trees. The hiking is not awful, but it’s getting late and dark, and we are pushing heavy bikes. It is the longest 2.5 miles any of us have ever hiked. A map I study later states the hike is 3 miles; I track the trail on Strava the next morning, and it comes up at 3.6.

Excerpt from Employment History, Stories, and Names, Kootenai National Forest, Rexford Ranger District:

FOURTH OF JULY FIRES, SNOWFALL AND GRIZZLIES AT MCGUIRE MOUNTAIN LOOKOUT

By Sid Workman, written May 1981

In the summer of 1931, my oldest brother, Wayne, was hired as lookout fireman and manned the McGuire Mountain lookout. My parents’ homestead was approximately 13 miles away and was accessible only by trail. My mother decided I was old enough (I was 12 at the time) to ride the trail by myself and spend the Fourth of July with my brother. I took an axe and a raincoat and a couple of sandwiches and some water. It was a dry trail. My horse was a good walker: He could travel 3½ to 4 miles an hour on the trail.

I was almost to the lookout after 4 hours on the trail when a hot electric storm moved in. Just as I arrived, my brother had located a fire quite some distance down McGuire Creek. It was arranged over the phone that Wayne take my horse and I stay at the lookout while he went to the fire. Well, I stayed the rest of that day July 3, the Fourth and until about noon July 5 when Wayne returned.

In the meantime, the temperature changed, and 4 inches of snow fell on the mountain. I reported about three times a day by phone to Rexford District, as was required by a lookout. We visited a few days after he came back, and I had an uneventful trip home.

Later that summer, brother Wayne killed a grizzly bear with a 30-30 carbine at the cabin door. The bear had walked around the cabin for two or three days, peering in and rattling the doors and windows, and sometimes had him cut off from visiting the outside “can.”

The McGuire Lookout is the most rustic of the three we stay in. The 12- x 12-foot structure was built in 1923 and is more like a cottage on the ground. Still, it has windows all around, with wooden shutters leaning up against the house. Before falling asleep the night before, while the winds rattled the windows, I thought about the phrase “batten down the hatches.” The lookout has a cupola that used to serve as the observatory to spot fires, and Kelly had made her bed in the cozy little loft space. The ride down the singletrack from McGuire is a highlight. We incur our only mechanical of the trip—a flat—in a steep, rocky, grassy section.

In contrast, we have lots of road riding today back to The Yaak. I’m not patient enough anymore for the monotony of road riding. After we backtrack down the dirt road and across the spooky bridge (just as eerie today as it was yesterday), I get hypnotized by the white line on the shoulder of Highway 92 somewhere around mile 8 of our 13-mile climb from the lake.

I’m bored, and I think about riding surfaces in order of best to worst: singletrack, doubletrack, 4×4 road, paved path, gravel road, chip seal, paved road. It doesn’t make the pedaling any easier; it only solidifies my current distaste for road riding, especially due to the 21-pound bike—loaded down with 19 pounds of supplies.

A previously run 5K has been chalked on the pavement, so we know that at about 3 kilometers from the summit, the thunderheads that began building a couple of hours earlier start to make noise, and at 2 kilometers, bolts of lightning shoot down from the black clouds. I count, “one-one thousand,” and the thunder booms. The rain comes in a cold downpour, then turns to sleet. Within just a few minutes, we are drenched and cold, but the storm passes as we near the summit. My knees have begun to hurt, so I am ecstatic when the climb is over. We cruise along the top for a bit, and the long Yaak River Valley opens up below. It is grand, with tributaries cutting in on the sides of fully forested slopes. Unlike Colorado, there are no luxury homes on the hillsides and no ranchettes with open swaths for grazing cows, no “cute” small mountain towns every 20 miles, no built developments. The rounded granite cap of Mt. Henry stands broad in the skyline. Fog is hunkering in the ravines, and the air smells clean. As if on cue, the clouds break and the sun comes out. Steam rises off of the pavement as we begin what is essentially a 30-mile descent. I’m 100 percent dry and warm by the time we roll up to the Yaak River Mercantile at 6:30 p.m.

To view the Firetower micro-site and to plan your own tour, click the banner below.