Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Winter 2021 Issue.

Chris Burkard is best known for his work as an adventure photographer. But in more recent years, he’s built a warranted reputation as an ultra-endurance athlete. In the summer of 2019, he set a new solo record on Iceland’s WOW Cyclothon, completing the 844-mile distance in 52 hours, 36 minutes, and 19 seconds. Chris returned in the summer of 2020 to complete a world-first, bikepacking 606 miles East to West through the Highlands of Iceland with Emily Batty, Eric Batty, and Adam Morka. Forever a glutton for punishment, he returned in 2021 for another bikepacking first and quite possibly his most demanding challenge to date, an unsupported winter fat bike expedition North to South through the highlands. This epic expedition would see Chris, Rebecca Rusch (American ultra-endurance pro-athlete), and Angus Morton (retired pro-cyclist) traverse 300+ miles through Iceland’s harsh winter interior. The riders were unsupported but were followed by a film crew in heavily modified vehicles that met alongside them when possible. While bikepacking the Highlands of Iceland during summertime is no easy task (I can vouch for that), the winter amplifies these challenges tenfold whilst creating new hardships and significantly more danger.

Chris, forever the gentleman, was a pleasure to interview, and it’s clear that the primary motivation in all his crazy adventures is his deep-rooted love of Iceland and his passion for storytelling. We discussed the similarities and overlap between bikepacking and vehicle overlanding and how both are a means to bring you closer to remote wilderness, enabling a more profound connection with the environment. I’ve had a long-standing admiration for Chris; his passion for life is infectious. And whilst he’s best known for his incredible images and filmmaking, I respect him most for his tireless efforts to give back to the photography and outdoor communities and his active contribution to environmental charities. Read on to delve into Chris’ motivations for pursuing photography, his passion for overlanding vehicles, the North to South expedition, and finally, his thoughts on pursuing your dreams.

At what point did you decide you wanted to be a photographer and was there a key moment that motivated that decision?

I was born in a small town and was eager to travel. Like so many 19 years olds, I was trying to figure things out. I quit school and my job, turning to photography as a Hail Mary. It wasn’t that I was overtly creative or wanting to express myself; rather, photography seemed like a way to [see the world]. Through the pursuit of photography, I eventually found a sense of purpose, and that was really special. That was the impetus in wanting to pick up a camera and use it.

I love your custom adventure-ready Sprinter and The Road to Inspiration film that documents the build. What were the goals for this vehicle?

I’ve been a huge fan of Expedition Portal and Overland Journal for years. The amount of time I’ve spent on that website is dangerous, [discovering] what I’m going to use, how I’m going to build it out—the forums are gold. Traveling on foot, by bike, horse, or overland vehicle, they’re all related, trying to get [us] deeper into remote wilderness. Each one has a role to play in creating an immersive experience, and that’s something I’ve always looked forward to in order to connect with the environment around me.

In regards to the Sprinter build, it has always been about functionality and ease of use. I’ve been in vans that have been built out to the nines and feature every accessory you can imagine. That’s very impressive and cool, but I think it’s different from a vehicle you need to rely on. I approach things [from a] function first [standpoint], whether that’s how I prepare bikes or the Sprinter build. There’s a lot of cross-pollination.

I know you have an appreciation for overlanding rigs. Any plans to explore this further moving forwards?

I’ve thought a lot about doing a proper overland-focused build-out, like a bed-off truck. I think what scares me is my attention to detail; if I commit to a build, there’s no way it’s going to be how I want it without spending considerable time and money. That said, I want to do it. I have a Toyota Tundra TRD on airbags, so the family and I take that thing out with a rad Scout camper, and that’s been our overlanding vehicle for the last year.

What do you think of the Icelandic Super Jeeps?

I [have] such a huge appreciation for the Icelandic vehicles [as well as] connections with the people who build them out. Every time I visit, I’m super keen to explore and spend time in and around them. Iceland is the mecca for building expedition vehicles. Those guys have set the stage for vehicles now used in the North and South Poles, Antarctica, Greenland—it’s pretty amazing.

How did cycling, and subsequently bikepacking, become part of your life?

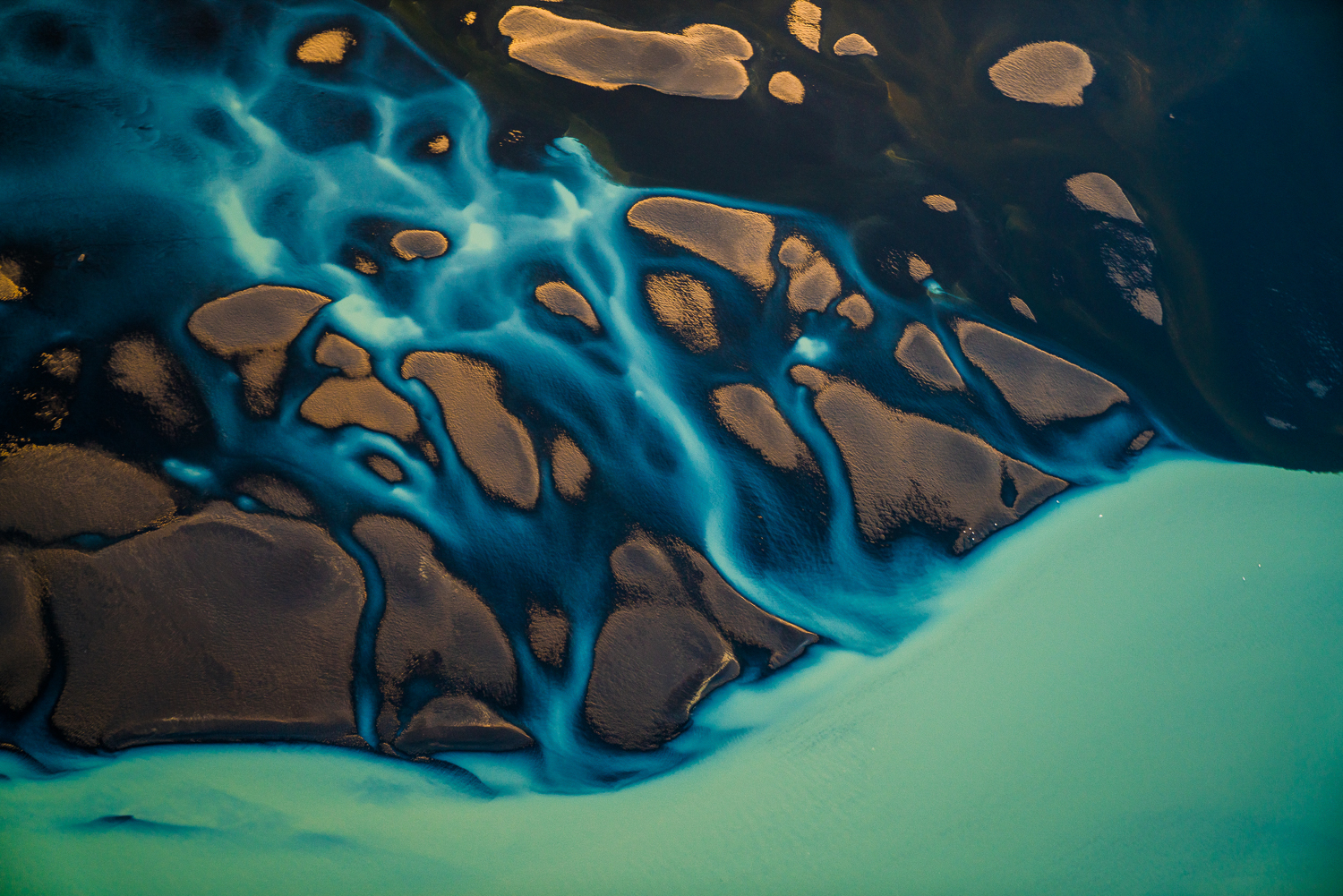

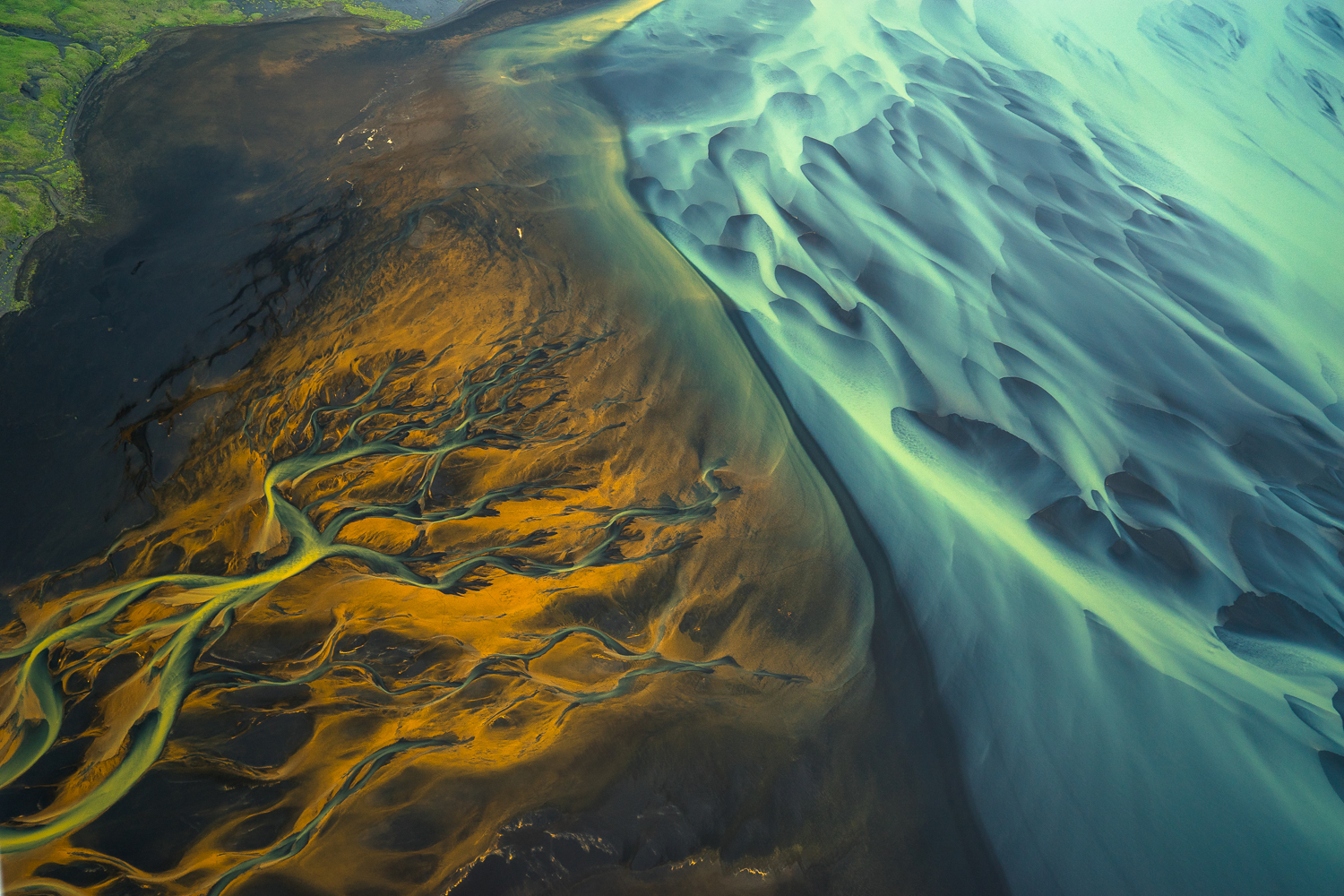

I have a hard time doing anything without fully investing in it. I started riding for the commute, and it developed from there. I have an office a mile from my house, and I was driving; it was stupid and such a waste. Cycling was the perfect way to be healthier and not burn fossil fuels; it was the gateway drug. I bought a bike off Craigslist for $400, and it was so much fun. Suddenly my commute was super interesting, engaging, and I felt empowered by that. Familiar roads became unfamiliar. It’s not simply about exercise; it fuels creativity, and that’s powerful. It’s a fresh perspective, like jumping in a plane and seeing a landscape from the air that you’ve known forever. Suddenly you see it in a completely different way; the bike provides the same.

Riding the usual route becomes boring, so I’d make small diversions to keep it fun. Then at a certain point, it became a way to be more immersed in the landscapes I’m passionate about. I love California; I love Utah; I love Iceland. The mega rides in Iceland came about because I love the environment and the opportunity to subject yourself in a way that is very raw, very real, very primal. That’s what bikepacking does; it strips back all the [nonsense] of daily life, calls, emails, etc. A lot of that stuff isn’t important in the grand scheme of things. The level of honesty that cycling brings out of a person, that’s what I crave.

We have to chat about the eruption of Iceland’s newest volcano, Geldingadalir, during your stay. What was it like to experience this wonder?

That was a crazy experience that I never expected to have in my lifetime. In some ways, luck favors the prepared. I’ve been there many times and always hoped to document an eruption. It was one of the most fulfilling things to set my eyes and camera on—the cherry on top of this trip.

What inspired the ride [North to South], and can you run through the objectives?

I’d already ridden around the country and bikepacked east to west through the highlands. However, someone had told me that Iceland in winter equaled freedom, and I never understood that. Planning for this trip, you suddenly realize that when there’s snow on the ground, you can ride almost anywhere. If conditions are right, you can point the bike in any direction; it’s like the whole country’s your skate park. So, this idea came about to ride north to south, coast to coast, on an unsupported fat bike expedition during wintertime. The end goal was to cross the Mýrdalsjökull glacier on bikes, which hadn’t been done before, and we did that.

It was seven days total, with one weather day—it was gnarly. We had three big days; a 20-plus- hour effort, one fourteen, one twelve, and that was just the time moving, pushing, riding—not total hours. The route was actually about 95 percent rideable, but when you’re pushing, you’re doing 1 mph, so that time adds up. We had some brutal days trying to get onto the highland plateau, riding/pushing 3,500 feet. Sometimes conditions were nice, but the wind was so strong it was dangerous to ride. Icelanders have a hundred names for snow, and we rode on just about every kind: soft, fresh pow; super wet; mash potato; super crust; and solid ice. There’s a finite amount that’s great to ride.

How much planning went into the expedition? Was the process reassuring, or did it amplify the risks and challenges?

Planning does amplify the challenges, but you’re so full of adrenaline for the experience that you don’t think about that stuff. It’s only in the moment that the risks and challenges hit you.

What did your support/film crew look like? What vehicles were they using to cross such an inhospitable landscape?

We were fully unsupported, but we had a film crew meeting up with us from time to time. The reality is they simply couldn’t travel through many of the places we could, but we met up where it made sense. We also wanted the freedom to be left on our own. They were using a highly modified Nissan Patrol and a monster Jeep with a 450-horsepower motor. They floated over snow; it was incredible. Some of the places they took those vehicles were mind-blowing. There were many occasions where the bikes were moving much faster (they tried to follow as close to our ride as possible). Our bike route was developed by an overlander, one of the best; he’s one of the guys who helped start Arctic Trucks. The four-wheel-drive community in Iceland knows winter travel in the highlands better than anyone. We relied on their expertise from previous trips to draw up a template that became the ride. There would be times they’d be on the road with you, then they’d disappear, and you wouldn’t see them for the rest of the day. There’s a real peace and significance in being completely alone out there, but it’s also important to recognize the danger or unknown and have sufficient support if something bad happens. I have a lot of respect for Icelandic search and rescue and didn’t want to have to call them out. That’s part of being responsible.

What did you take home from your previous East to West crossing of Iceland, and did you apply these lessons, if any, to your North to South ride?

It was more the cumulative knowledge of 44 trips to Iceland. I’ve just learned so much about that environment. How and when do I feel safe? When am I pushing it or not? When the weather’s changing, or the best time of year to do things? In the spring, the most dangerous weather is when it’s +1°C, and the snow’s melting on you. We did experience that once or twice; it made us very cautious.

Was this your first extended fat bike expedition?

Yes, I like being a novice. On fat bikes, all your suspension is built into the tires; the bike handles so differently from anything else you’ve ever ridden. The gyro stabilization effect of a fat bike is wild; it’s hard to turn, steer, and balance. It was almost like learning to ride again.

Any new high-calorie recipes for this trip?

This trip was different, and we had to rely more on the food that was there and available (I arrived a month and a half prior to the ride). It was one of those scenarios where we all had a slightly different approach. I was more focused on high fat, Gus was taking anything he could get hold of, and Rebecca had pre-made more food. You have such deep fatigue from the cold that you’re trying to get calories in any way you can. Diet goes out of the window, and you’re just looking for the densest high-calorie food that can be stored easily. Carrying so much food meant the first few days were brutal; it was so much weight. Day one, we went through a town, so we tried not to consume any of our packed food. But then we had five days with no supply points, bar one small hut café serving burgers that was much needed. The small things on a trip like this become so significant.

Notable euphoric moments? On the flip side, any scary instances?

The funny thing is they both happened on the same day. That morning we started on one of the most glorious days I’ve had in my life. It felt like we were riding inside of a painting or some kind of 3D-animated experience. I was blown away by how visceral and incredible that felt and have been relishing that moment ever since. That was followed by this huge challenging day.

The crux of the trip was moving over the glacier. We had this epic weather window, and with a storm on the way, we knew that our goal of crossing the glacier was going to end. It would’ve meant being stuck in a mountain cabin for a couple of days and then crossing the glacier with fresh snow, which would’ve been really hard. We decided to go for it, and that’s the night I think we all remember. Some of us got frostbite on our fingers after having to change a tire on the glacier in -20°C. The sealant in our tubeless tires was coagulating because we had to run such low psi to get traction. In those moments, it’s crazy how quickly things get scary. That said, I think that lack of preparedness is the beauty of these trips. You’re constantly guessing and not sure what will happen next. Dealing with the unknown is so important to personal growth.

Has this adventure inspired any bikepacking trips for the future?

I feel like my mind has been opened up to what winter bikepacking travel is like. I feel more excited about the prospects and less afraid. Beforehand, you have all these worries: Are you going to get frostbite? Or not survive? Afterward, you gain this confidence and wonder about other places like Greenland. I have a lot of friends who do winter expeditions. I don’t feel like this is my primary calling, but I respect it a lot. If part of telling deep and meaningful stories requires a winter expedition, then I’d love to do it.

How do the struggles and accomplishments of expeditions contribute to new ideas or professional work?

I always hope these trips translate into my career in some way. To transform it into a storytelling narrative or take away some deeper understanding or awareness—that excites me. That’s the space I’ve tried to occupy most, learning to be a better storyteller. Perhaps it’s not about directly translating these experiences into work opportunities, but just the ability to relate them to people. Being the participant, getting that experience firsthand is key.

After so many international adventures, is there any other place you’d consider calling home? Is Iceland a contender?

Yes, I’ve set myself up with the opportunity to perhaps call Iceland home someday. I would be honored to do so; I can’t think of another place as meaningful or significant to me.

How has success in your field impacted your approach to photography? What continues to motivate you?

I think it was Galen Rowell, wilderness photographer, who said photography was for the active participator, not just the bystander. When you’re on a commercial set, you see [things] happen from a distance, but often you want to be more closely involved in that moment. I found this to be valuable. I want experiences in places where I can learn more about that environment and hopefully incorporate that into my work.

Let’s time travel. What advice would you give Chris Burkard the day he decided he wanted to pursue adventure photography?

I would say travel the world based on what inspires you, rather than simply chasing a paycheck or trying to keep editors happy. The latter for a certain minute will give you some sense of joy, but you’re fulfilling someone else’s needs, and long-term, it won’t provide the same satisfaction. It’s crucial to find a career path that’s fulfilling, that gives you something meaningful. It should feel like sleep’s not an option, as you’re so connected to the experience. That’s the greatest gift you could give yourself, the opportunity to love and cherish what you do to the point it doesn’t feel like work.

Books by Chris Burkard: At Glacier’s End (latest book), The Boy Who Spoke To the Earth, High Tide: A Surf Odyssey, Distant Shores, California Surf Project, Under An Arctic Sky Photo Book.

For more, read Bikepacking Iceland by Jack Mac.

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to ensure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.