Editor’s note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Summer 2021 Issue.

Bell-bottoms and platform shoes are en vogue. Bee Gees’ disco hits top the music charts while Grease is the must-see film of the summer. Stephen King publishes The Stand, Cold War tensions will continue for another 13 years, and the Berlin Wall will remain in one piece for another decade. There are no cell phones, no electronic navigation devices, no Google. Travelers use hand-drawn or Russian satellite maps and compasses for navigation and communicate by letter. Highly anticipated, hand-scrawled updates from the road take weeks to arrive in loved ones’ mailboxes back home. It’s 1978—the world in which a young Lilli Mixich began her travels.

During a camping trip in Spain, touring in a shiny orange Opel Ascona and a ground tent, Lilli and her partner temporarily ditched their saloon car in Tarifa to join a bus tour heading for Tangier, Morocco. Not sure what to expect, the couple arrived in Northern Africa and found a whole new world outside of Europe. Lilli recalls what it felt like to arrive on another continent for the first time. “What I remember most of this trip were the unusual but wonderful aromatic scents, the shouts of the muezzin which woke us up every morning, and the congested roads and twisted alleyways of the souks in the old city. We were fascinated and wanted to come back to explore more of this unknown land.”

And so started Lilli’s lifelong love affair with Africa. Forty years later, Lilli is now in her sixties and a self-proclaimed “social media junkie” traveling solo through Eastern and Southern Africa in her tiger-striped 1988 Toyota Land Cruiser HJ60 named Toyo. Whether for short-term trips, long-term overland travels, to live, or to work, the urge to explore has brought this German overlander back to African soil countless times over the past four decades. She has lost her heart to Africa, and after delving into a lifetime’s worth of memories, it is easy to understand why.

Your first overland trip was from Germany to Morocco back in 1979 in a Land Rover 109. Why did you and your partner at the time choose this vehicle for the journey?

We wanted to return to Morocco. But in a shiny Opel Ascona? No way. We wanted an off-road 4WD vehicle. Land Rover was more popular than Toyota at this stage, so when we came back from our holidays in Spain, we quickly traded in the Ascona, and the Land Rover 109 became our new baby. We built the vehicle up as a van and slept inside with a little sink and a cooker so we could wash and cook inside if the weather was bad.

What did you learn from this six-week trip to North Africa?

Before the trip, you plan so much and think you have to do it a certain way because you don’t know any other way. We organized the trip very well and planned every minute of it, aiming to drive 200 to 300 kilometers per day. I found out that wasn’t the way I wanted to do it. I wanted much more freedom, skipping some places that are not so interesting and staying longer in others.

It is quite a distance from Germany to Morocco, and it took us nearly a week to get there and a week to get back. It was too much. You fly over everything and aren’t going deeper into it. After the first journey to Morocco, we had a different approach. No plans, no daily distances. Drive whatever we drive and stop along the way.

Your next trip to Africa was two years later, in 1982, this time for two months. What was it like exploring a bit deeper into Africa?

We saved up holidays for two years for this trip, traveling down West Africa and crossing the Sahara into Mali. I must say that the farther I went down into Africa, the more I liked it, and the more interesting it became for me. We made plans for the next year to cross down to West Africa on the other side of the ocean. We started in the Mediterranean and wanted to see the Atlantic. When you have the right car and love the people and the landscape, you want to see more and always push farther and farther.

–

After a few years of short touring trips in Africa, you resumed full-time school in Germany. How did this impact your travel plans?

You cannot go to the Sahara in the summer as it is too hot, so my partner and I started backpacking through Asia for six weeks each year. I must say I don’t like backpacking so much. You have to carry this bloody heavy backpack. We also [stayed in] the cheapest hotels. I enjoyed Malaysia, Bali, and Thailand, especially the sea and the islands, but missed the nature of Africa and its wild, natural landscapes. I really loved taking the car and a little home with us.

During one of your backpacking stints, an experience in Asia inspired you and your partner to plan a long-term overland trip through Africa. How did this come about?

We met a lot of people on long-term backpacking trips in Asia: three months, six months, and one guy we met had been traveling for seven years. I thought, Seven years—I want to make an open-ended journey. So, there was a turning point where we decided to prepare for [such a] trip. I finished school, and it was the perfect time to sell everything and fulfill this dream. We spent three years on the road from 1987 to 1990, traveling from North to South Africa in the Land Rover 109 through Tunisia, Algeria, Mali, Mauritania, Guinea, Senegal, Gambia, Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Zaire (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Rwanda, Tanzania, Kenya, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, and finally to South Africa.

What were the highlights of your three-year Africa trip?

The hike to see the gorillas in former Zaire and our trip through the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in Botswana. My favorite place was and still is a campsite on the Indian Ocean in Kenya; it has not changed much, and I regularly return to it. Out of all the people we met, the one I remember most was the owner of a workshop in South Africa who repaired the broken engine of our Land Rover for no cost. He served in the war in Angola and had to do penance for some deaths he caused. He had to do good on us. It was a very moving story.

After three years of overlanding through Africa, you and your partner returned to Europe for a short time before emigrating to South Africa in 1990. What brought about this change?

My partner missed having a professional career and didn’t want to go on traveling forever. We tried to find a company which would send him to South Africa for work. He didn’t find anything out of Europe, but after emigrating to South Africa, he found a job quite easily. I followed later.

My partner had a good salary and a successful career in South Africa. For women, it was different; we were still not earning that much money, and you had to work a lot with very few holidays compared to what we were used to in Germany. When we lived in Africa, we wanted to be there and explore but had no chance to enjoy it because we worked all the time. One good thing, though, was I went to work in the morning with my sunglasses on and returned home in the evening with my sunglasses on because it was always sunny outside.

After three years living in South Africa, you returned to Germany in 1993. What sparked this change?

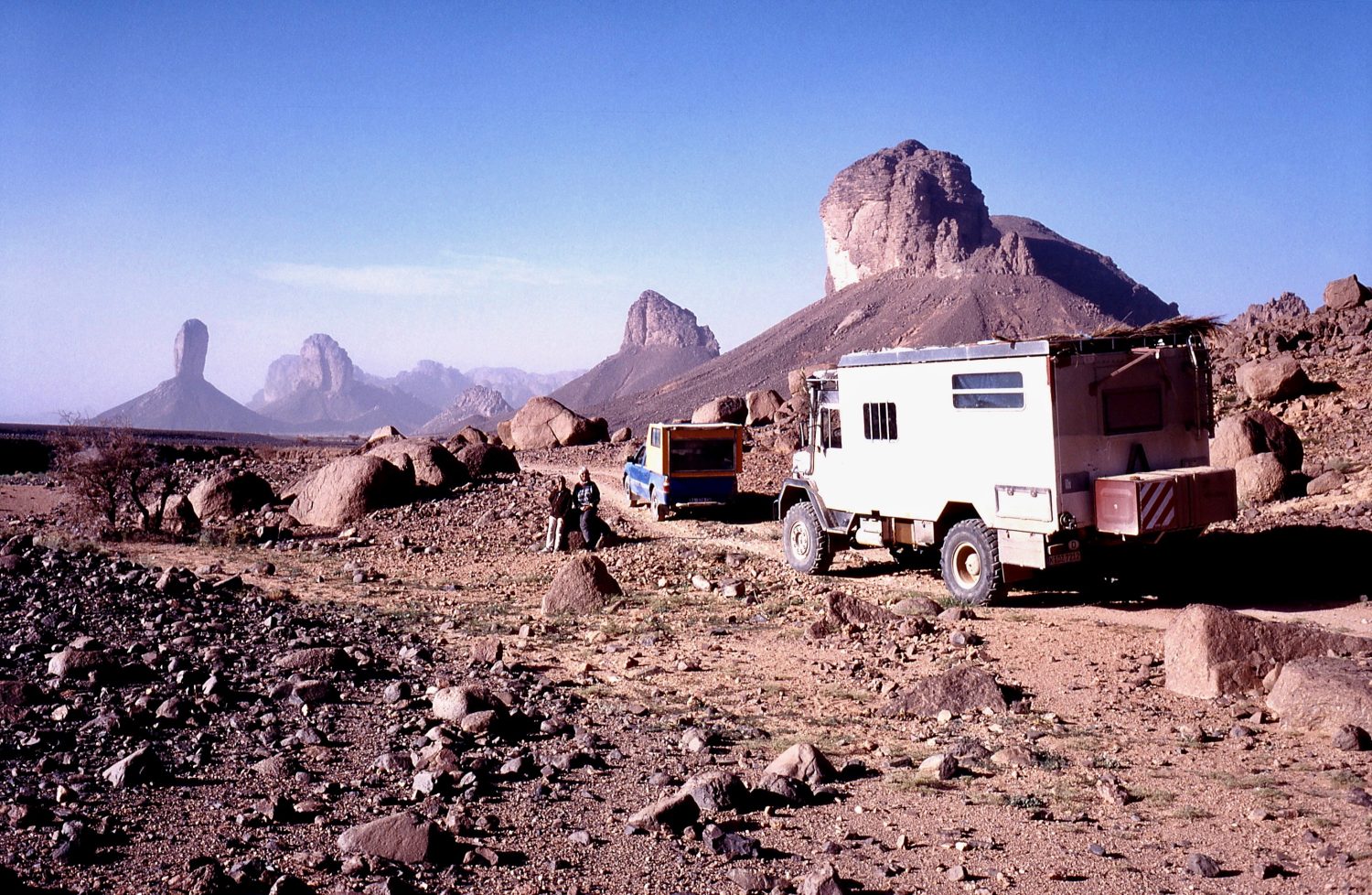

The relationship with my partner broke down. He wanted a career, and I wanted to travel. I returned to Germany and fell in love with Thomas, who I eventually married. He founded a company called Alu-Star, which built expedition vehicles. It was one of the first companies to build unique expedition vehicles using aluminum as it is very light. I helped with the business, and we didn’t have a lot of time to travel as we were self-employed. We did [make] a few short trips into the Sahara during that time.

You and Thomas worked for another nine years together in this business, which was very successful. What pushed the two of you to sell the company and head out on the road?

We could have worked in it until retirement. A friend asked us, ‘Are you working to make a lot of money or because you want to fulfill a dream?’ Thomas and I were in our mid-forties at the time. We found a friend to take over the business (he is running the company to this day), sold everything, and then traveled for 10 years until 2012. The first plan was to drive to India in our yellow Magirus Deutz expedition vehicle. Thomas had been to Australia, and I had traveled Africa extensively, so we wanted a new experience. But a friend of ours working in Tanzania had a grey Magirus Deutz lorry built in Europe and was looking for someone to drive it to him in Tanzania. Thomas and I agreed to do it. That was my third crossing of Africa. Of course, when I put my foot on the African continent again, I was hooked.

–

Once you arrived in Tanzania, you and Thomas purchased a 1988 Toyota Land Cruiser HJ60, which you still own today. What was the build-out of this vehicle like?

Cars were quite cheap and readily available at that time. Thomas had extensive experience building cars, so he added bars on the windows to prevent monkeys from getting inside (we had this experience in Nigeria) and a bed in the back. We just took what we had, built the Toyota up, and traveled throughout Africa for a year and a half. We met wonderful people and really enjoyed it.

At this point, you and your husband began a decade of travel that could only be described as an overlander’s dream: hopping between Europe, Africa, and Australia, with your expedition lorry parked in Germany, the Land Cruiser in Africa, and an ex-bush ambulance in Australia. What brought the two of you to Australia?

A customer asked Thomas if he could build a truck in Australia rather than having it shipped to Germany to work on. We moved to Australia short-term and bought a Toyota HJ47 ex-bush ambulance there. It was so easy and fantastic to travel in Australia. Thomas worked for 2 months, and we traveled for 10, extending our 6-month visa for a year. After that, we visited Australia two times a year, lived out of our lorry in Europe for three to five months, and spent the rest of our time in Africa. We never ended up making it to India.

What are your favorite memories from your time in Australia?

The most exciting place was Cape York Peninsula—we traveled there for about four months. The most dangerous and scary experience was our illegal and out-of-season crossing of the Simpson Desert. We were all alone in this huge area, possibly without help for up to a month if our vehicle broke down.

The most inspiring person I met was a girl who walked the entire Canning Stock Route of 1,900 kilometers in Western Australia on foot with her three camels, a strong stallion, a mare, and their [foal]. Her stallion died en route due to food poisoning, and she had to continue with [only] the mare, foal, and two small camels. The mare couldn’t carry all of her luggage, so we drove part of the route with her and carried her excess luggage. Her daily walking rate was 35 kilometers. She started at sunrise, we started later in the day, and we met daily in the afternoon at the wells which dot the route. She showed me that you can do whatever you want in life.

In 2012 you and your husband experienced a painful separation. How did this affect your travel plans?

At age 55, this was the first time in my life being single. I was suddenly alone and wondered, What am I going to do? I never did any of the driving as both of my partners liked driving very much. I was always the navigator and made the plans. For the first two years after the separation, I worked in Africa for the winter and returned to Germany in the summertime. I moved into a little VW bus in Germany, but it was too small, so I bought myself a bigger mobile home and lived in that.

How did living in and learning to drive the mobile home in Europe help you build the confidence to travel by yourself in Africa?

I had no trust in myself that I could drive an off-road vehicle, but I wanted to live in Africa full-time. So, I bought the mobile home in Germany and started traveling in Europe with it. I started slow. I had to find trust in myself first before jumping into more difficult terrain like in Africa. That was my first time spending six months on the road by myself. I also learned that you must be able to be alone with yourself. This is a big thing. There is nobody around, nobody to talk to. You must find a way to make decisions on your own.

How did you become comfortable with the mechanical side of vehicle-based travel?

Initially, I had no feeling for the steering wheel, for the heaviness of the car; I was so nervous. I was afraid of having to change a tire or having a breakdown. It took me quite a while to take the responsibility, to say, Lilli, it’s your life now, your freedom. You want to go traveling. No one is taking you by the hand. Nobody else can make a plan for you. It was hard. It took me more than a year to adjust and take responsibility. Now, because I am alone, and the car is the key to my personal freedom, I have to take care of it. After three and a half years of driving an off-road vehicle, I know it inside and out.

I experienced many situations involving vehicle problems with both of my partners. I knew a lot because I’ve been through a lot. But in the past, I didn’t have to worry because the man did the work. But for me, it was about recalling the memories—for example, changing a flat tire. I had seen it done before, so in theory, I knew. But there is a big difference in doing it and experiencing it yourself. You can only learn it when you do it, so you just have to jump into the deep water.

A tire change is very easy for me now. In a national park one time, I was busy fitting my jack and checking tire pressure, and a man jumped out of a car and said, ‘Can I help you? Have you got a flat tire?’ I was so euphoric and said, “No, you cannot help me. I know exactly how to change a tire, but can you take my picture for Instagram?”

What have you learned from your extensive experience traveling in a variety of different overland vehicles?

Everyone has to find out their own travel style and what is best for them. If you travel greater distances, perhaps better suspension is required. Or if someone travels quickly, maybe they don’t need as much living space inside the vehicle. Try out different models to see which features you don’t like and the ones you do. Maybe you aren’t figuring it out over a weekend, but you’ll eventually find out what you need.

The Magirus Deutz expedition truck had a lot of living space with a fixed bed, bathroom, kitchen, and a place to sit. But for the tracks that I love to drive in Africa, the truck is too big. Many of the dirt tracks that go to interesting places are made for small cars like Toyotas. None of them are made for lorries, which have wheels that are farther apart, so you’re always driving with one wheel in the bush. Locals cut down trees for firewood on the side of these tracks, so you have all of these sticks and branches sticking out, which can kill your tires. Driving big lorries also destroys the sand tracks for others because your tires flatten the track walls.

In cold locations, I like the living space inside the big trucks. But for hot countries where you spend more time outside, I prefer a small car. Toyo, my Land Cruiser, is made to my requirements and has been developed over a long time. I love to sit inside in the morning and read or sort pictures. The roof has been extended, so I have more headspace to sit upright, and I can just jump into the car and have my bed ready. If I’m in a national park, I can take my things out and lie down in bed but still see everything outside and enjoy the view.

Do you feel safe as a solo female traveler?

I do, actually. Especially at my age, people are very respectful. I have no security issues, not at all. People are normally friendly and helpful.

It is true I cannot handle more difficult breakdowns because the car is built up and has many unique features. When this happens, I’m not in such a remote area that nobody comes again. I find someone to travel with me, or I bring enough food and water so I could stay at that location for a few days. I also know the seasons and how they affect the road conditions. For example, I wouldn’t drive in the off-season into a wilderness area where nobody else would choose to drive.

How has travel changed in Africa since you first stepped foot on the continent in 1978?

The Central African Republic isn’t driven anymore. Overlanders take either the western route along the coast or the eastern route through Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt. The thing about Africa is there is always a route. Situations might be changing, more difficult, or more expensive, but it is possible, and people do go.

Another big difference is communication. Back in the ’80s, there was no WhatsApp, Facebook, or Skype. The internet had just started back then. We had to write letters, which arrived six weeks later, and then we had to wait for weeks until we got a letter back from home. You could not search Google. There were no detailed maps. In the Sahara, people still drew hand-drawn maps. Old Russian satellite maps were good because they included topography. You could buy these maps in off-road shops back in the 1980s. In Mali, we translated scientific publications about landscapes from ecological expeditions to find the best places. We bought one travel book, Durch Afrika by Klaus and Erika Därr, which covered all of Africa. But the information was already two to three years old when it was published. Before navigation devices, you would sit in the car with a book, a compass, and a hand-drawn map to figure things out.

There were also no ATMs 30 years ago. You had to carry cash and traveler’s cheques. We had a credit card but couldn’t pay for it online, and no bank would have given you money on your credit card. One thing that hasn’t changed is the people. Now they might have a mobile phone and more connection, but they are still tending to their field and looking after their children. Landscape- and wildlife-wise, there are more regulations, but things look the same. If you drive through the African bush, you feel like you are the very first person discovering it.

You mention you’ve lost your heart to Africa. What draws you back over and over again?

I love the people and their openness, friendliness, and trust in life. Their smiles are real, and they love to laugh. The wilderness—there is no continent in the world like Africa. There are so many unknowns. You don’t know what is behind the next corner or bush or where you will be sleeping at night. It’s kind of a thrill.

The primordial landscapes of the African savannah are like balm for my restless soul and allow me to rediscover a kind of silence within myself. Mankind had its origins here, and it feels like nothing has changed in two million years or will change in the next millennia. The wild animals will still roam the plains in an endless rhythm. It’s like coming home, home to Mama Africa.

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to make sure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.