For the few of us in the know, Elspeth Beard has long been regarded as a living legend. But in recent years she has transcended her underground status and is finally getting the recognition she deserves—for being the first British woman to ride a motorcycle around the world.

I first met Elspeth in 2009 when I interviewed her for a documentary I was making about women adventure riders. Her wry humour, coupled with a warm welcome and typically British understated sensibility regarding her impressive life story, made for fascinating conversation. We met at her home, a self-converted water tower in Surrey, just southwest of London where she has lived since returning from her epic ride in the mid-1980s. Her willingness to take on a derelict Victorian structure and turn it into an award-winning home with her bare hands, while bringing up a young son alone is testament to her fearlessness, tenacity, and optimism—traits she says are a direct product of her time on the road.

Her two-and-a-half year journey began in 1982. Along the way, she witnessed riots and civil uprisings that altered the course of nations, and suffered permanent scars and memory loss from physical maladies and major accidents. She even managed to fall in and out of love with three men. What better ingredients for some serious character building?

Her trip would still be considered impressive nowadays, but the fact that she was a young woman in her early 20s, setting off alone with no sponsorship or support in an age before email, cell phones, and sat navs makes her journey all the more remarkable.

Please give us some insight into the young Elspeth. Were there any aspects of your family or background that may have influenced your life path?

I grew up in central London with my elder sister and younger brother; both my parents were doctors and worked full time. Looking back, my childhood was fairly unconventional. Family life was always very happy and harmonious, but we were given a lot of freedom and very much left to our own devices. My father was a renowned psychiatrist and very eccentric—he didn’t care what people thought of him and was always in his own world. I was sent off to a private boarding school at the age of 10 where I stayed until I was expelled at 16.

Coming from a poor family, my father’s obsession with saving money meant that he always repaired and fixed everything himself, teaching himself the required skills from books. Like him, I was very practical and developed a similar mindset and “cando” approach to life.

How did you get into motorcycling?

I first rode a bike when I was 16. A friend was taking his Husqvarna down to Salisbury Plain and asked me along. I can’t say I was instantly hooked, but shortly after this I bought a Yamaha YB100 as a cheap and efficient way of getting around London. A year later I upgraded to a Honda CB250N and realised the travelling potential of a bike. I soon got bored with the Honda and in 1979 bought a secondhand BMW R60/6. It was a 1974 model with about 30,000 miles on the clock.

What gave you the idea for your big trip, and what was your motorcycling experience at this point?

With my BMW I felt I could go anywhere. It gave me an immense sense of freedom and over the next couple of years I gradually travelled further afield, starting with a tour of Scotland, then Ireland, progressing to a 2-month trip around Europe in the summer of 1980. The following summer I persuaded my brother to meet me in Los Angeles where we bought an old BMW R75/5 and rode to Detroit together. All these trips gradually built up my confidence, not only about travelling but also how to look after myself and my bike. The seed had been sown but it was a combination of events in my life the following year that prompted my hasty departure.

What was the main appeal of the trip?

After 3 years studying architecture I graduated with a very poor degree and started to question whether I should continue. These doubts were combined with a relationship split and I needed to get away. Wanting to travel, I set about preparing a vague plan to ride around the world. I really didn’t know how far I would get, and having ridden across the United States the year before I decided to start in New York City and just take it step-by-step. Leaving with only £2,500, I knew this would not be enough money but I hoped it would get me to New Zealand or Australia where I could work to replenish my funds.

How did your parents react to your plan?

Having worked in accident and emergency, my mother hated motorbikes and did her utmost to stop me—she even threatened to disinherit me. But my parents’ resistance only made me more determined. In fairness to my mother, she didn’t comprehend anything that was unconventional and her apparent lack of interest was probably her way of dealing with my trip. Like any good mother, she worried about her children and in her view my life had taken a wrong turn. As for my father, he was entirely in his own little world.

Did you have any dealings with the media and the motorcycle press at the time?

Several months before I left, I sent out letters to BMW and various magazines asking if they would be interested in following my journey. I had enclosed a photograph of myself on my bike and offered to write and send back articles for publication. I only received two replies. One was a very polite letter from BMW in Munich wishing me luck, but basically saying that they already knew their bikes were the best for long distance travel so they didn’t need the publicity. However the response from the British motorcycling press was very different.

Dear Elspeth,

Brecon said he’d write this letter but he can’t ’cos [sic] his tongues jammed his typewriter. Julian asks if you’ve got an [sic]eight feet tall husband who’s also a karate expert?

Mike Clements has already formed the Elspeth Beard Appreciation Society and wants to know where in the world you’re going to be so he can get there first.

Me? I’d like to offer you sponsorship around the world but I think that’d be a waste and a shame for London.

Best wishes,

Dave Calderwood Editor [of Bike Magazine]

It made me angry that they could dismiss me so casually and treat me with so little respect. At that moment I became more determined than ever to show them and all the other doubters that I could do it without their help.

How did you prepare for your trip?

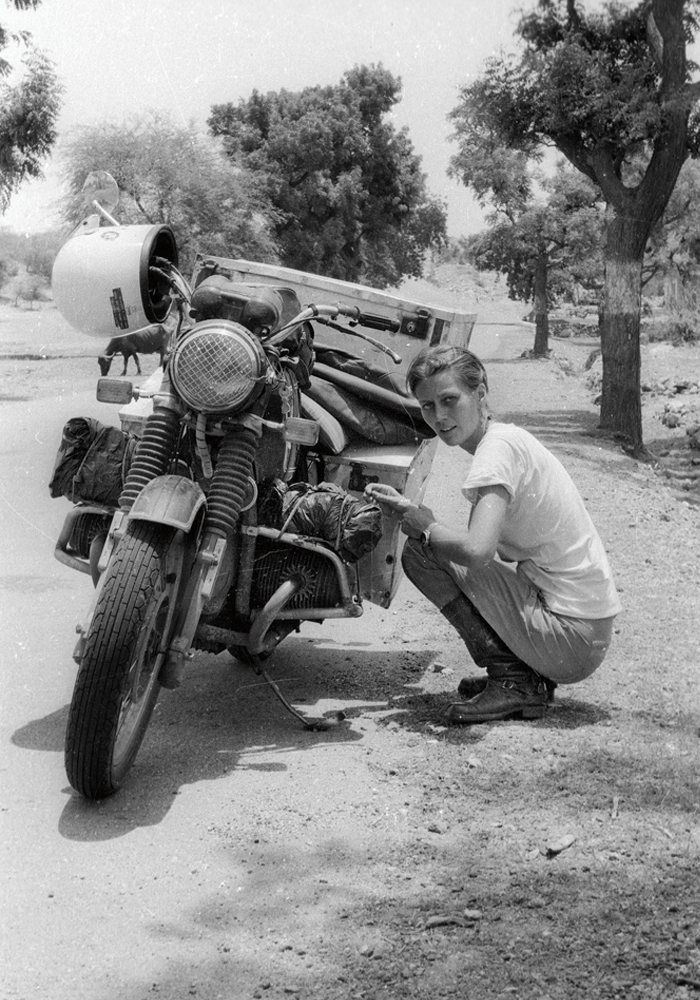

Before I left I learnt as much as I could about my bike. I bought a Haynes manual and set about stripping down parts of the engine and getting a basic understanding of how it all worked. My bike was now 8 years old and had already done 45,000 miles. I replaced all the cables, bought a new battery, changed the oils, and put new tyres on. I also took the cylinder heads off to fit an extra base gasket in order to lower the compression. I didn’t really know what I was doing, but I had been told by a friendly mechanic at the BMW shop that this would be a good idea.

My luggage consisted of my throw-over panniers, a tank bag, and a nylon bag I just strapped on the back seat. This luggage got me to Sydney where I decided that I needed something more secure. Aluminium luggage did not exist then so I set about making my own. The panniers and top box consisted of aluminium sheets wrapped around and riveted onto aluminium angle. The joints were then siliconed to make the whole ensemble waterproof. They were light, lockable, easily repairable, and relatively cheap to make. Perfect!

As for my riding gear, this was fairly basic compared to today’s standards. I had an old [1973] full-face Bell helmet, my Lewis Leathers leather jacket and boots, and a pair of Belstaff oiled cotton over trousers. I wore the same gear for the entire trip.

How did it feel to be on the road? Did you have any misgivings in those first few days?

When I left New York City I was apprehensive and questioned what I was doing and why. When riding across the States I would plan every day down to the last detail, usually several days or sometimes weeks ahead, constantly checking my bike every time I stopped. With my limited funds I needed to get to Australia, where I hoped to earn more money. So I had to keep moving and would ride 400 to 500 miles every day. It was Australia, where the unexpected often happened and everyday was unpredictable, that taught me to take one day at a time. But by the time I reached India I had learnt to take one hour at a time.

What were the high points of the journey?

The high point of my trip was undoubtedly meeting and falling in love with Robert. Having travelled on my own for over a year and a half, it changed everything. I had not seen a fellow long-distance motorcycle traveller, and neither had Robert—it was a rare sight in those days.

We bumped into each other on the streets of Kathmandu. We both stopped dead, jumped off our bikes, and then sat on the side of the road and talked nonstop for over 3 hours. Robert was Dutch and had emigrated to Australia a couple of years earlier. But he hadn’t been able to settle so he decided to ride his bike back to Holland. With Robert, my trip changed from dayto- day survival to something that almost started to feel like a holiday. The risks when travelling alone are far greater, and mentally you have to be very strong. I had become very weary of always having to sort out [issues] entirely on my own. Whether it was problems with my bike or being ill or simply trying to find the right road, just having someone to share and discuss things with made all the difference. It no longer felt like an endurance test.

And were there low points?

I was hospitalised twice, survived life-threatening illnesses and two brutal accidents, and had to fend off physical and sexual attacks, biker gangs, and corrupt police who were convinced I was trafficking drugs.

What turned out to be your biggest challenges? Were they the same ones you envisaged before you left?

I naturally worried about being a woman travelling alone, but I felt safe when on the bike wearing my full-face helmet. With very few women riding bikes in those days it was always assumed I was male. I was very conscious of my appearance and always wore the most unattractive ill-fitting clothes I could find so as not to draw any attention to myself. I was acutely aware of my vulnerability and the possibility of being raped or attacked, but this was a risk I accepted and tried to mentally prepare for. Another fear was having an accident and lying injured in a ditch all alone thousands of miles from anywhere. With no way of contacting anyone, I worried about my chances of survival and did not want to die alone.

How did people react to you?

It was a surprise to me that I often found people in third-world countries to be friendlier than in countries considered to be more civilised. In America I was often treated as a dirty, greasy biker who had to be trouble—they wouldn’t serve me in petrol stations until I took my helmet off and realised I was female. Then, when they heard my British accent they couldn’t do enough for me. The Australian Outback was probably one of the most unfriendly, inhospitable places I travelled. Arriving at a roadhouse it would fall silent; I was then usually ignored and would end up having to help myself to some water from an outside tap. Southeast Asia couldn’t have been more different. People were friendly, helpful, and inquisitive, but not intrusive. India seemed to be a hundred years behind the rest of the world. Having never seen a large motorbike before, let alone being ridden by a woman, the locals stared at me relentlessly as if I’d dropped in from outer space.

Do you think being a solo woman on the road was ever advantageous?

I think a lone female traveller will always be seen as an easy target, but I strongly believe that if you exude confidence, hold your head up high, and look purposeful you will significantly reduce the risks. It’s also important to understand how to use your perceived vulnerability. With my helmet on I could pretend to be male, but if I needed help I could take it off, shake my hair, and beam a wide smile. You have to learn to play the game to survive. Locals did not perceive me as a threat, and there were many occasions when I was invited to stay with them because they were worried for my safety. I’m not sure I would have received the same hospitality if I had been male. When I started to travel with Robert I certainly noticed a difference; with a male companion it seemed I no longer required protection.

There was no Internet, mobile phone, or GPS in the early ’80s. Do you think this is a better way to travel? Has something been lost with the arrival of technology?

Things are certainly easier nowadays—most bikes are more reliable with every imaginable accessory available, and modern riding gear is far superior. However, the biggest change is the information available now and the fact that you can find out about anything and everything, anywhere, and all at your fingertips via a smartphone. This takes away the fear of the unknown and provides a degree of comfort, which encourages many more people to take to the road.

The journey for me was not about sitting on my bike for 4 to 5 hours a day. It was about the experiences, the people you encounter, the breakdowns, the accidents, getting lost, and the bizarre situations you find yourself in when the unexpected happens. With so much technology and information available, these experiences are minimised and there’s a danger that the journey is no longer an adventure but simply a series of days riding a bike.

I recall many times when I was lost and had to ask one of the locals the way. I would then often be invited to join them for tea, then dinner, and then asked to stay with the family for the night. It’s those experiences that are the journey, and they don’t happen when you are following a red line on your GPS.

Upon your return you got straight into having your son and buying/restoring the water tower. Do you think your experiences on the road gave you the confidence to take on big projects like this?

I returned home at the end of 1984. It was not easy after such an adventure, when living life on the open road had been so intense. I had lived every minute of every day for over 2 years. No one wanted to know about it, or understood what I had experienced, which made me feel very lonely and isolated. Keeping to myself I returned to college and finished my architecture degree, having little interaction with anyone. In October 1988 a friend told me about a 130-foot-high derelict Victorian water tower for sale. The moment I saw the tower I knew I had to have it and bought it without a moment’s hesitation. The next 7 years were spent restoring and converting the water tower into my home.

This was the toughest time in my life, and worse than anything I had encountered on my trip. In the space of 6 months I became a mother, lost my father to a heart attack, and was forced to move out of my childhood home and live on a building site with a 6-month-old baby. I also became a single mum and discovered that I had to deal with everything all on my own. To pull myself through I used to think about all the trials and tribulations from my trip. However grim the situation seemed at first, I always somehow managed to haul myself through it and that gave me the inner strength I needed to survive.

After more than 30 years you are suddenly becoming well known. Are you enjoying your newfound status after having been ignored by the press? I find it extraordinary that people are interested in something I did over 30 years ago when, at the time, no one wanted to know. If my story can now inspire other people, especially women, to believe that there are no limits to what can be achieved with self-belief and determination, then this gives a whole new meaning to my trip. It completely changed my life and made me the person I am—it gave me the confidence to take on anything life can throw at me without any fear.

What does your future hold and are you still riding? Would you do another long-distance ride?

I am still riding today and have four motorbikes. My old trusty R60/6 is still running and has remained a very important part of my life, but my everyday bike is a BMW R80GS Basic which I love. I have two smaller trail bikes that I use for rallies and riding the green lanes. I have never stopped travelling but I can’t see that I would embark on another solo round the- world trip. It’s often best to keep your memories intact.

A book detailing Elspeth’s epic journey, Lone Rider, will be released in July 2017. Michael O’Mara Books, mombooks.com, ISBN 978-1782438076.