“Would you like to see Stanley’s compass?” It was a gray, drizzly morning in southwest England. The man standing next to me opened a small wooden box, removed a weathered brass compass, and carefully handed it to me. I queried, “Henry Morton Stanley?” He replied, “Yes, this is the compass Stanley was carrying when he found Livingstone. It was a gift to me from the family.” Casting an eye around his charming home-office I noticed display cases of medals, photos of my host with dignitaries, crocodiles, and elephants, various artifacts, and maps from around the world.

I became aware of Colonel John Blashford-Snell in 1997 while researching a trip to South America. I had been most intrigued with his 1971 crossing of the Darién Gap, but further investigation revealed a character right out of a Hollywood screenplay—a professional soldier, explorer, leader of men, humanitarian, and renaissance man. But he was the flesh-and-blood real deal. When the opportunity arose to spend an afternoon with the Colonel at his home in England, it was not an invitation to pass up. Videographer Bruce Dorn and I arrived as he was pulling a quiche from the oven. He served us and we settled in at the table for lunch with one of the most interesting men I’ve had the pleasure of meeting.

“Did you notice the machine gun in the hall? My grandfather brought it back from the War [WWI]. Would you like some tea?”

Interview

Who were the people who inspired you to pursue a life of adventure?

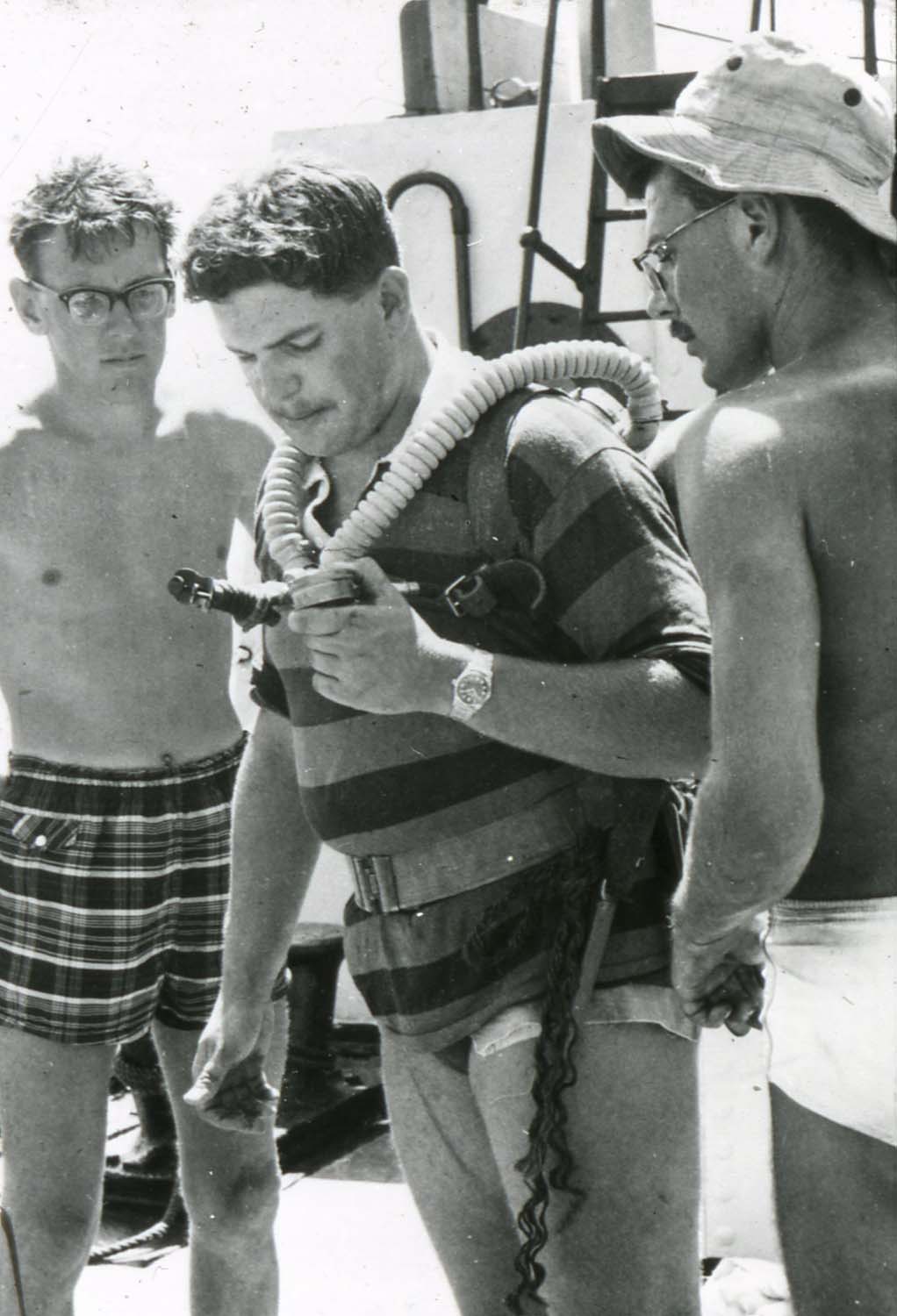

My father and mother had been around the world. They’d been in New Zealand, had lived and worked with the Maori, had a Model T Ford they used to drive around in, and rode horses everywhere. They really had an adventurous life. When the war [WWII] ended I went off back to school in Jersey. It was a wonderful place for adventure, and one thing that had developed was underwater swimming. There were two people that inspired me: one was Hans Hass and the other was Jacques Cousteau. As kids, all we wanted was an Aqua-Lung. The others were Stanley and Livingstone, both of which were very underprivileged children. Stanley was an illegitimate child from a Welsh workhouse. Livingstone was the son of an impoverished tea peddler from Scotland. Look what they made of life.

When I finished school I got into the military and attended the Royal Academy at Sandhurst. You had a choice as to whether to go into the cavalry, the infantry, the engineers, or whatever. I chose the engineers and my job was to find non-military activities to do all over the world. Many things followed out of this.

In 1968 you led the first descent of the Blue Nile. How did that project come about?

That came about from the training we did in Ethiopia. During the war my godfather had looked after the Emperor Haile Selassie. I was training cadets at the time and thought, what better than to do it in Ethiopia. During a meeting with the Emperor he said, “I hope you will come back to my empire.” I replied that I’d love to and asked what he would like us to do? Without closing an eye he said, “Explore my Blue Nile.” I thought…Crikey!

After I got back to Britain a letter arrived and my general sent for me. He said, “We have a letter from Haile Selassie, king of kings, chosen line of the tribe of Judah. He wants you to explore his Blue Nile.” I explained that it was rather dangerous and that there were snakes, crocodiles, bandits, and hippos. He looked at me and said, “You’re being negative, and I don’t like negative officers.” He thought this was just the sort of thing the Army needed to buck up morale and give them a challenge. He continued, “I’ve decided we shall do this expedition. I shall be chairman and you shall be secretary. I see no need for anyone else.” I was told to get off and run this expedition. And of course, it turned into a complete epic. From this we then founded the Scientific Exploration Society.

What was the core purpose of the SES?

The idea was to bring together people from all nations who wanted to do something interesting and challenging. It started out with a group of friends and gradually expanded into what it is now, which is about 600 members around the world. We became involved with the Explorers Club and various other organizations, and had links with people around the world…not only with armies but scientists as well.

We took on a lot of tasks that usually had a mixture of adventure and exploration. For example, the Darién Gap Expedition wasn’t a question of [if we] could we get cars through the Darién. It was a question of what you could do for the zoology and biology, the fauna and flora, and also the indigenous people who were undoubtedly going to be threatened by a road that was supposed to go through their lands.

Can you tell us more about the Darién Gap?

I was working for the Ministry of Defense at the time and was summoned to lunch at the headquarters for the Anglo-Hispanic organization in London—anything to get lunch out of the Ministry of Defense was a treat. I was greeted by a general with an eyeglass and a proper bowler hat, a most extraordinary chap. He asked if anyone had heard of the Darién Gap. I’d been reading about a place called Darien in Russia and said, “Oh yes, it’s in Russia.” He screamed, “No, it’s not in Russia. It’s between Panama and Columbia.”

He was heading a committee to find a route through the Darién. It was an international effort set up in Bogota, Colombia, for the nations in South America who felt it would improve the economy. There had been several attempts but all had failed, and there was much negative publicity. He asked if I thought I could get a road through. I said I didn’t know, I’d never seen the Darién and never been to South America. In the end he asked me to do it. The government told me, “You go do it. This is a great thing. We’ll help you and lend you aircraft. But if anything goes wrong we shall disown you.”

I sent a mad Irishman friend to walk through it first and report back. He returned emaciated and full of every possible disease, and said, “You can do it but don’t ask me to go with you.” We formed the team and got involved with Rover, who was just about to produce the new Range Rover. They said it would be great if we would take Range Rovers to show how wonderful they were.

At the time there were political issues between Panama, Colombia, and America. We were caught in the middle and were the only ones who could talk to them all. We formed a force of Americans, Panamanians, Colombians, and British, all of whom could talk somewhat to each other. The entire expedition was to drive the Range Rovers from Alaska, through America and the Darién, and on to Tierra del Fuego.

Were you prepared for the jungle environment of the Darién?

I thought so. I’d worked in Africa a lot, in Ethiopia. It’s jungle but not as thick as the South American jungle. When I got into the Darién it was very different, very wet. Instead of having a dry trip we had a very muddy one. It clogged up the cars and became a hellish sort of journey. The tires weren’t the right sort and the cars had a number of problems. We broke nine back axles. The engines were enormously powerful, but the power would come down and the wheels would not move. Something had to go and it was the differentials. They just exploded. In fact the teeth came up through the floorboard like a shell. Luckily, no one was sitting in the back or they would have been hit by the shrapnel. We had a hell of a job with the Range Rover, particularly when we dropped one in a river.

Range Rover redesigned the entire differential, which had to be flown by helicopter and dropped by parachute into the jungle. In the meantime we had to push on. We managed to find a battered old Land Rover in Panama City. We took off the doors, the tailgate, everything we could, so it could be lifted by four men. That vehicle went ahead with the engineers. We called it the Pathfinder.

We had two little tracked vehicles called Hillbillies, but they got bogged up in mud and were useless. They are still there in the jungle. But this marvelous old Land Rover went ahead with the engineers, who were making bridges and cutting trees. When we sorted out the issue with the Range Rovers, they roared ahead on the track the engineers had made. We had a little aircraft, a Beaver, which would drop various supplies. The Americans helped with helicopter support drops, as did the Colombians. But it was quite a bit of effort to get all these nations to work together when they didn’t like each other much. The big problem was the need to cross the Gap in the time of dry season. When we finished in the village of Chigorodó the skies opened. We made it with only eight hours to spare.

As an expedition leader, was there anything specific you took away from that experience?

If anything I became a stronger conservationist, with even more interest in the problems of indigenous people. A lot of the work I’ve been involved with since has to do with the protection and conservation of wildlife, of the fauna and flora and environment, as well as education.

Can you tell us about some of those projects?

One of the other big expeditions we did was on the Congo. We were looking into a terrible disease called onchocerciasis, which had blinded about 20 million people. It’s caused by a worm that gets in the skin and gravitates to the back of the eye. We’d taken in a large team of medical experts to investigate this disease. The press from this event was pretty big and we had a number of officers who were equerries to the Prince of Wales, Prince Charles.

When I returned to England, the Prince called and requested that I come to see him. He said he was most impressed with the fact that we had taken young people. And we had. We’d taken a young man from Colorado and two guys from Jersey, and when they returned home these boys went lecturing at other schools and colleges. The Prince said, “If you can do this with two or three guys, why can’t you do it with two or three hundred?” I stated that there was nothing stopping us, but it would take a large amount of money. “How much money do you want?” he responded.

I had a meeting with friends and came up with the idea that if we went around the world in a sailing boat, we could have young people coming along. They could have some time sailing and some time on land doing community and conservation tasks. It was all aimed to give them experience and self-reliance, so they would become leaders and pioneers themselves. The one condition was that when they returned to their home countries they were expected to put something back into their communities. Operation Drake was born. We had the Eye of the Wind as our flagship and went around the world. It took two years.

What are some of the most memorable vehicle-based expeditions you have done?

Expeditions in the Sahara, especially with the Army, were very memorable. They were much smaller and we were crossing huge areas of sand and desert, usually in Land Rovers. You were totally dependent on your vehicle. If you broke down, and we did sometimes, often in the middle of nowhere, you could probably die. We saw the wreckage of vehicles that hadn’t made it. That reminded us to check our vehicles very carefully. In those days though, four-wheel drives were much simpler than they are now. You could do everything with a spanner.

On one Sahara expedition to the far south, we found the remains of one of the battles of the Long Range Desert Group. They’d all been shot up and the guys had been killed or captured…except for three. On a hill near the wreckage of one vehicle we found a pile of empty cartridge cases, an old camera, and a toothbrush. It belonged to a soldier who had escaped before the Italians came in with their armored cars and finished off the column. In the wreckage he found two more men who were still alive. He got them up on their feet, managed to scrounge water from the broken radiators, and then they marched. They marched 200 miles towards the south and were eventually discovered by a French patrol.

Have there been times that you’ve found yourself out of your comfort zone?

Oh, frequently…frequently, of course. I got stuck several times myself, had near misses, and wondered what the hell was going to happen to me. My radio was broken down, no one knew where I was, and I’d stupidly gone off with only one vehicle, which you should never do. I don’t know that I’ve been completely lost. I usually knew where I was, but I couldn’t get from where I was to where I wanted to go. It’s a slightly different problem. And then occasionally one will be attacked.

Attacked? Have you had any close calls?

People will ask me about the most dangerous animal I’ve been in contact with. My answer is mankind. On the Blue Nile we had two gunfights with bandits. There were about 40 of them and about 10 of us. Fortunately they weren’t very good shots.

Then about five years ago I had a terrible accident in Bolivia on the Road of Death. We were going back to La Paz in a bus. It was at night and we had a good driver, but he got too close to the cliff. We came around the bend and hit a clump of rock sticking out. It hit the windshield, fell on top of him, and knocked him out. I woke up and the bus was going all over the place. The co-driver had grabbed the wheel and we careened down the road for about 500 yards. I was trying to get into the cab to help but couldn’t make it. Luckily the co-driver managed to grab the wheel and pushed it hard. We crashed into the cliff and stopped. You feel there is a good Lord watching over you when you survive something like that.

You were involved with a number of conservation projects in Nepal, including one with a mammoth elephant.

That started while I was on my way to Tibet. I’d stopped for lunch in Kathmandu, as one does, with a man who worked with the wildlife department. He had a problem and asked if I could help. He said that in the west of the country the locals say they’ve got a mammoth. I said, “A MAMMOTH? It can’t be, they died off millions of years ago.” I said that if he got me a photograph of it I would come and investigate. A couple of years afterwards a girl came into my office with some pictures and said, “There you are, here’s your mammoth.” It was this huge elephant with a domed head, very long tail, an extremely fat body, and about the shape of a mammoth.

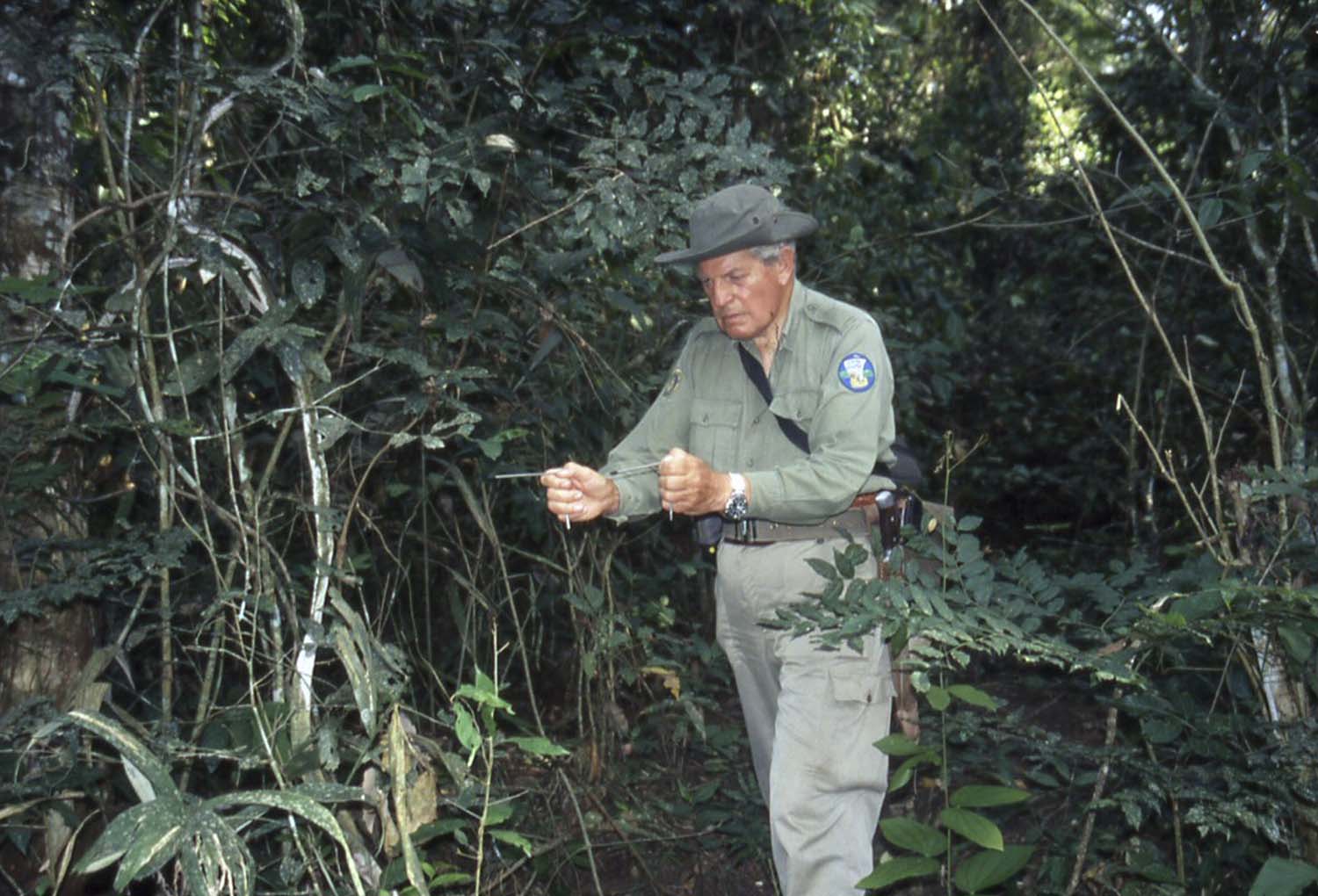

We went to Nepal with some instructors from the Drake project, hired domestic elephants, and rode into the jungle. The first year all we found was a big footprint, 22.5 inches across, which indicated that this creature was 11 foot, 3 inches at the shoulder. The second year we went back and discovered the creature. They were huge. There was not one, but two giant bulls with huge tusks. We filmed them and it went out on CNN and was shown around the world.

We launched a third expedition and found not only these two but others, and finally the whole herd. They were living in an area of forest where no one ever went in West Nepal near a village called Bardiya. It was a royal hunting reserve but the king hadn’t hunted there for years. So they had been left alone to develop on their own. We took DNA from dung and from one that had died. They turned out to be an Asian elephant. The great thing that happened out of all of this was that the Nepalese Wildlife Department, after realizing they had an unusual creature, sent in soldiers to guard the area. By protecting the elephant they protected all the other animals, such as the Bengal tiger and the rhino. Bardiya is now the most wonderful reserve.

White water rafting in Nepal.

I’ve heard a tale of a grand piano in Guyana…

It was called the Grand Adventure, after the grand piano we were taking to a remote [Wai Wai Indian] village. We flew it to the farthest airstrip, dragged it several miles across the pampas, through the jungle, and then to the village. The only way to do it was to go up the river, but there were rapids. The only boat we could find was a canoe with an 8-horsepower outboard, which wasn’t very powerful. By some miracle we got the thing loaded on the boat and we shot up the rapids. We managed to work our way up to the top and were going slower and slower and slower. I was waiting for it to breach and go sideways. We would have been really sunk. We were met by about 100 Indians and we got the piano to the village. It played for several years, more than we hoped, and it persuaded the young people to entertain themselves there rather than going to the coast to find work and amuse themselves. They were musical people and I think the piano helped to hold the tribe together.

The Grand Expedition successfully delivered a grand piano to a remote Wai Wai Indian village, Guyana.

How many expeditions do you have pending at any given time?

We probably work about one or two years ahead. The Scientific Exploration Society gets lots of bids, but then we have to do reconnaissance and investigate the possibilities and do the fundraising. So they don’t all come off, but most of them do.

John Blashford-Snell has worked extensively with the Just a Drop organization to provide clean drinking water to developing communities around the world; Ecuador, 2008. justadrop.org

These expeditions could cost a considerable sum of money. How have you financed them?

I’ve written 15 books now, and they do help, but books on exploration don’t sell in the millions. Television has helped a little bit, but again, they haven’t got the money these days. Newspapers are another source, but also limited. In the end, the majority of the money you raise comes from the people who take part. It might cost £2,500 to £3,000 pounds each, and you don’t live in luxury. If we are doing a well project we will probably get a grant from Just a Drop. Occasionally foundations will help, and Zenith Watch has also been very generous.

I understand you have a special ritual after each expedition.

At the end of every expedition we have Burns night, in honor of Robbie Burns, a Scot Poet. It’s a traditional party where you eat haggis, drink whiskey, dance, and recite poems. After one expedition in Panama we asked the local chief if we could use one of his large round houses, and if he would come as our guest. I explained that we would have dancing and he said, “Dancing, yes. Can we dance with you? Can we bring the women from the village to dance?” The party went well, the whiskey came out, the music came on, and the village women came in…they were all topless! There were all these beautiful tits leaping around the floor, and actually, dancing with topless women is a bit off-putting. You can fling a woman around when she is fully dressed, but when she’s got nothing up top it’s kind of tricky.”

You’ve explored much of the world. Are there white spaces left on the map?

They are getting fewer. The really unexplored areas today are probably in the jungle, in the higher mountains, and certainly underwater. There are also little niches in the Sahara Desert where very little is known. I’m interested at the moment with the new discoveries in photography where they can actually penetrate through jungle canopy and photograph the stonework underneath. I think a lot of archeological discoveries will be made this way.

What is on the horizon?

I’ve been working a lot with charities and programs with inner-city children. I’m hoping to give kids, who perhaps haven’t been as fortunate as I was, a chance. Helping them pull themselves up by their bootstraps and do something worthwhile with their lives. In Devon we have some sailing boats where we take kids to sea for a week at a time, give them a chance to see something they normally wouldn’t see. They come onboard and have to clean, cook, and pull up the sails…do everything themselves. It gives them a sense of adventure. It has a very good affect. We’ve also taken disabled children. There is no shortage of children and opportunities.

How does someone go about getting involved with one of your expeditions?

They can go to the SES website and write in. We arrange to meet, explain what we are going to do, and look at what the person has done before and what they can contribute. Maybe they are a doctor or dentist. Engineers are good people to have along, but even general handymen are good for helping in the villages, and farmers can assist with agricultural needs. Quite frankly, if you are fit enough to run and catch a bus, you can probably do it.

Operation Drake’s flagship, Eye of the Wind, shadowed by the Goodyear blimp during it’s two-year voyage around the world (1978-1980).

What is the greatest misconception about John Blashford-Snell?

Never believe your own PR. I think anyone who appears on television or the like, builds themselves up to be more than they really are. In the end, everyone’s socks smell the same. Everything I’ve done has really been a team of people. The Darién Gap is a typical example. You couldn’t do that with one man. You can only do it with a bunch of nutty guys who are willing to carry it out. It was the same with the Congo and Blue Nile expeditions. Even more so with the Drake project. I think the real essence is to choose the right people. I’ve spent a lot of time studying people, meeting with them, and getting a feel for what they are like. You want to find out how people will react when they are scared stiff.

At 77 years of age the Colonel shows no signs of slowing. After our meeting he flew to Mongolia in search of the Przewalski’s horse.

What advice would you have for someone who is an aspiring adventurer and wanted to make a difference?

Have confidence in yourself! Confidence is a great thing. Other than that I say to follow your heart’s desire. Maybe that means getting into some sort of career like photography or writing. It’s no use just doing nothing and saying, “I want to be an explorer and adventurer.” You’ve got to have some other skill to go with it. I would also say learn to communicate. The greatest attribute of leadership is the ability to communicate and inspire. If you can do those two things you can lead.

Learn more about Colonel John Blashford-Snell’s life of adventure in his new autobiography, Something Lost Behind the Ranges, ISBN 978-0002550345.