Smitten with life, UK adventuress Lois Pryce has always been on the move. At 13 years of age, an unchaperoned, week-long trip on bicycles through Cornwall’s back roads with friends introduced her to the possibilities of travel by design. And also to the idea of minimalist travel, taking shelter where you can find it, and bringing little more than bare essentials.

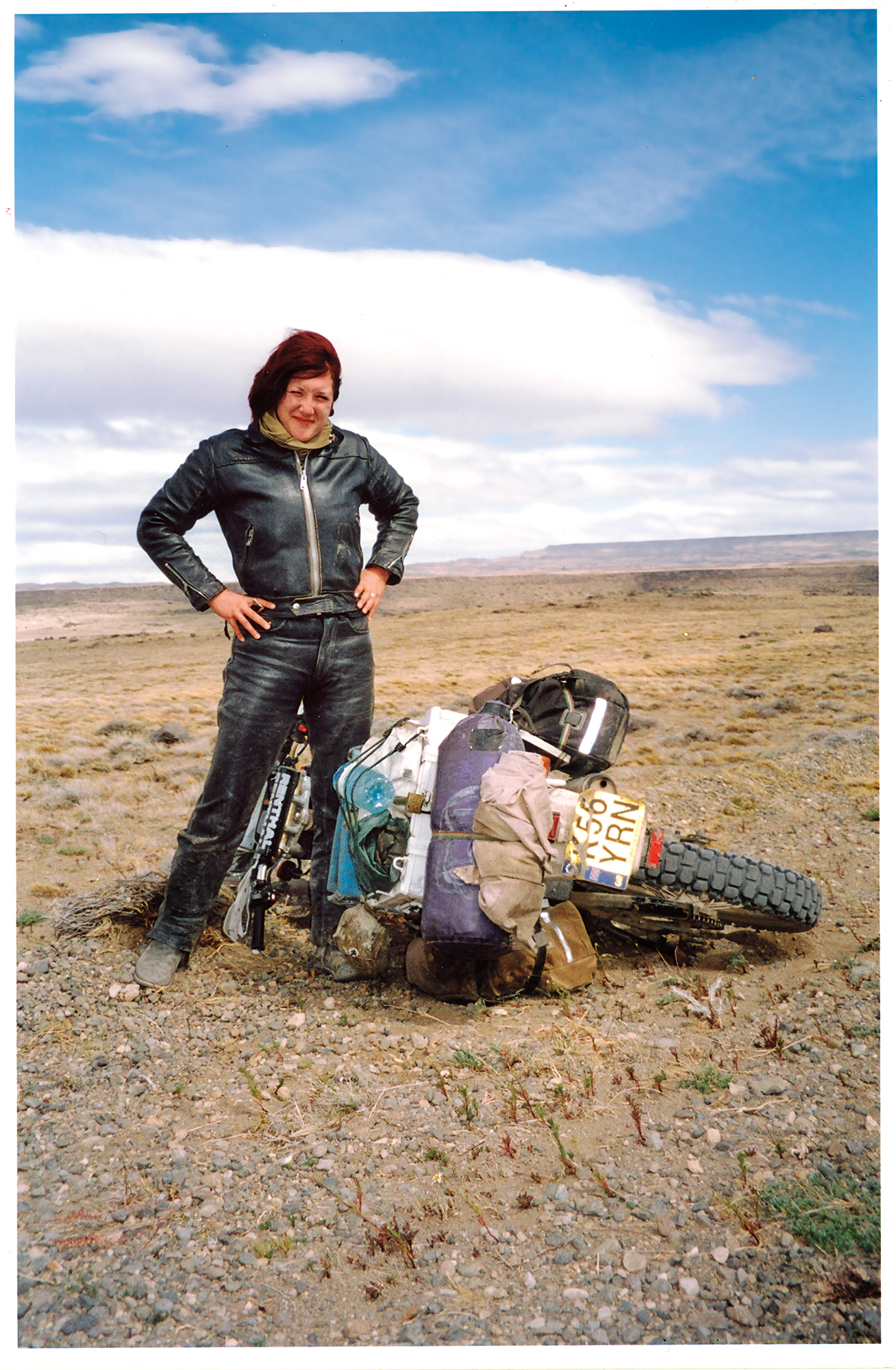

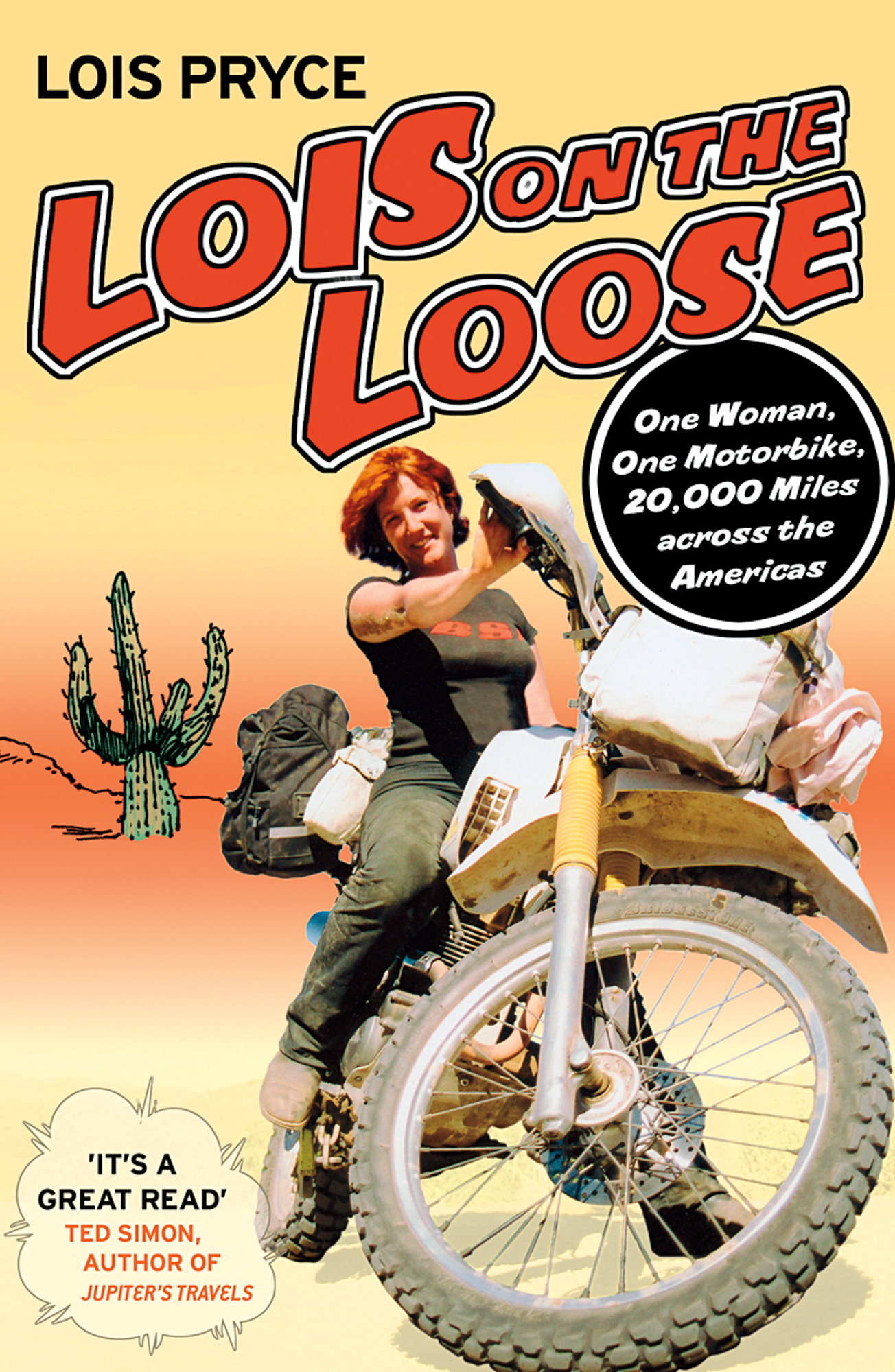

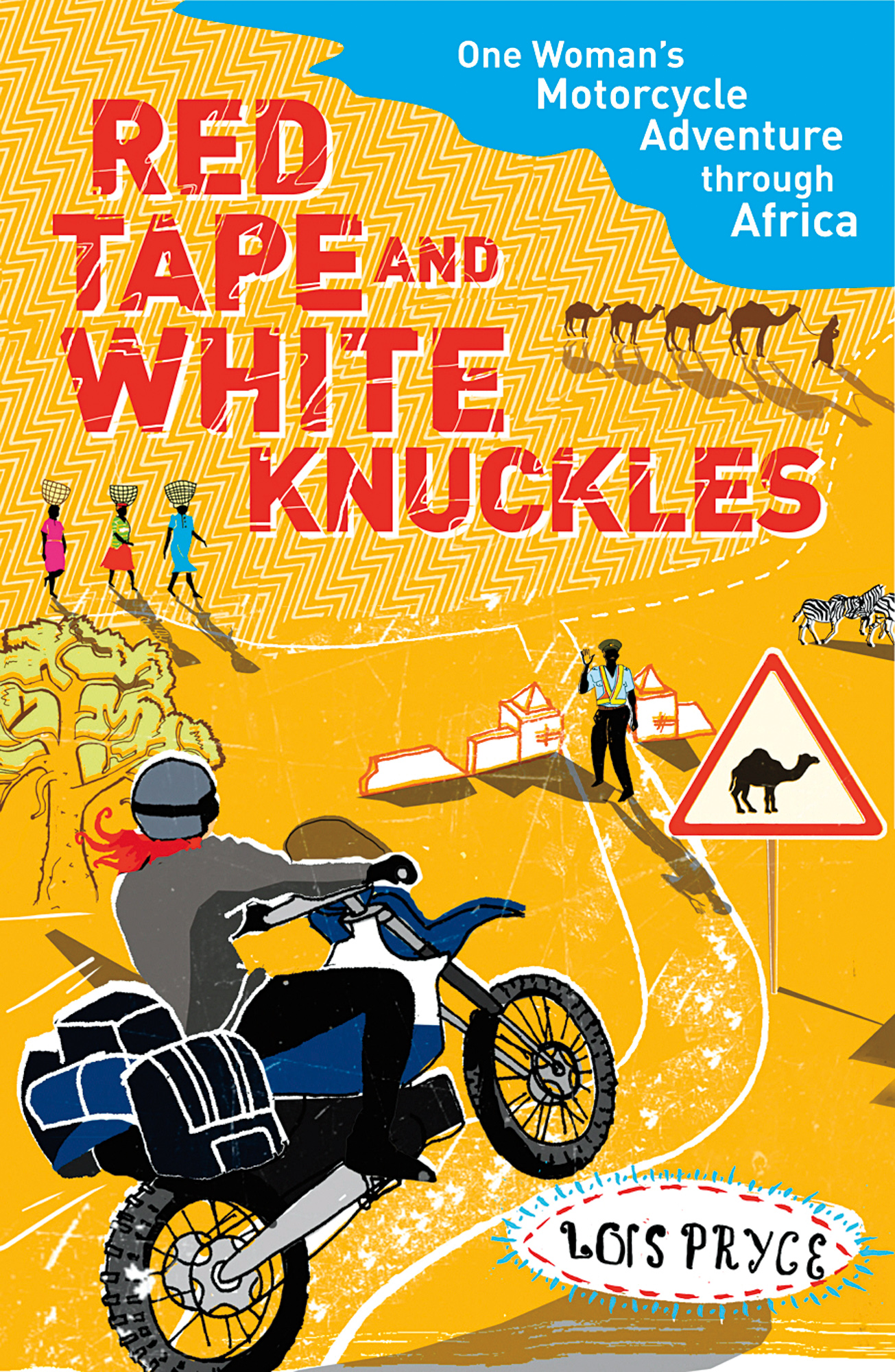

When Lois was 28 years old, she learned how to ride a motorbike. It wasn’t long thereafter that she decided to take her job and shove it, knowing that life in the corporate world, be it in a cubicle or corner office was not for her. Like many others before her, she found herself declaring “there must be more to life than this.” Lois soon found herself pursuing a ribbon of roads and trails the length of the Americas. In a test of will and wit, she traveled solo and continues to do so to this day. London to Cape Town followed, along with all the challenges Africa had to offer such as crossing the Sahara, Congo, and Angola. Early lessons included embracing her vulnerability, enabling her to make more human connections, which according to Lois, are what makes your experiences “meaningful and real.” Along with leaving the extra clobber and gadgetry behind, she also dropped her ego, if indeed there was one to drop. After all, it isn’t about “taking on the world, it’s about being in it.”

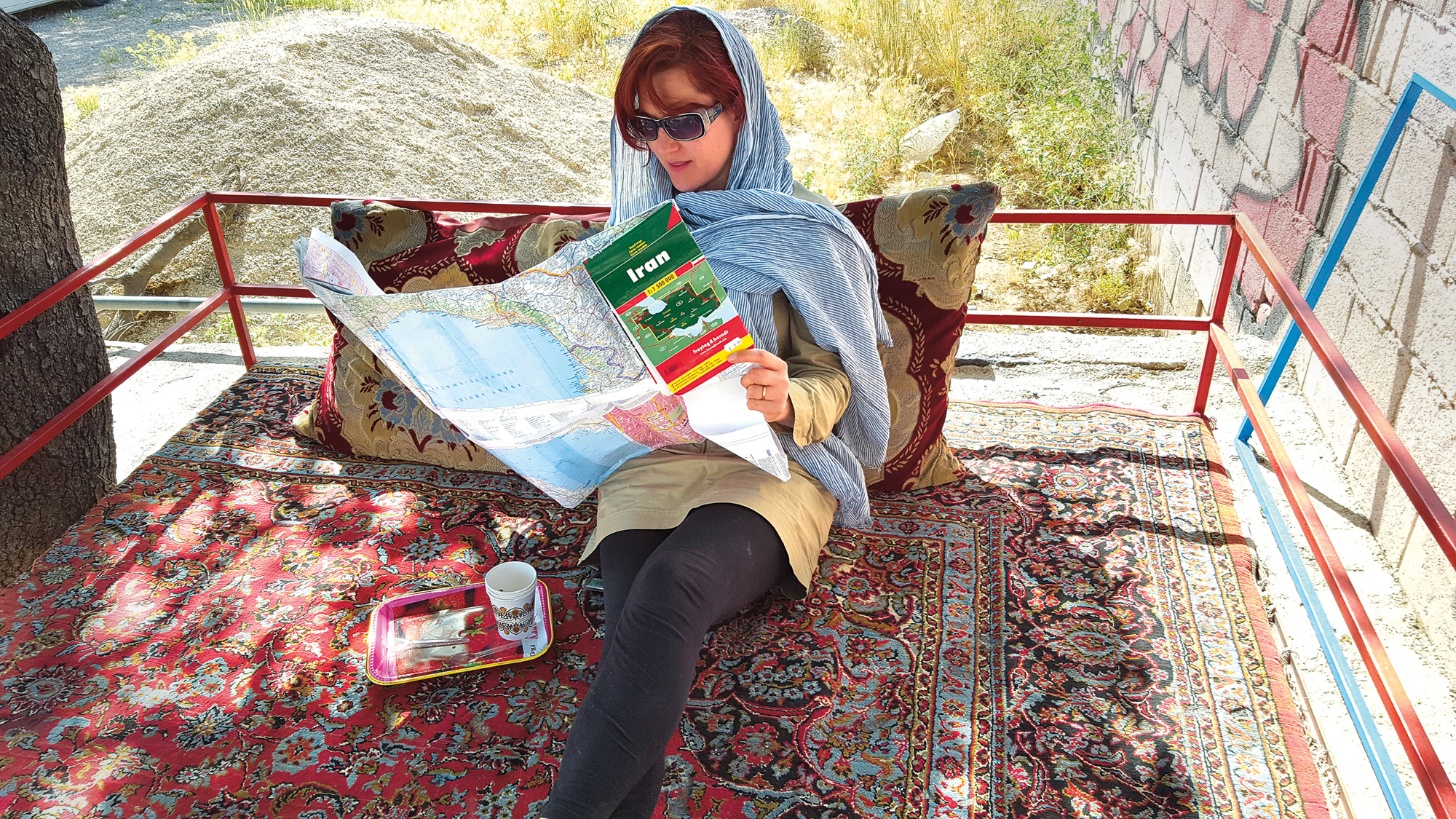

The willingness to allow yourself to be lost is another key component in Lois’ mindset. She discards GPS in favor of carrying paper maps and asking for directions directly, which often leads to further conversations with locals, and often, invitations back to their homes. Noting the “horrible, panicky feeling” one gets when truly lost, but also recognizing that there is always a way out of your predicament by engaging in your surroundings and asking for help, puts a positive spin on a situation that many are uncomfortable with. A woman of many hats, brilliant red locks poking out from each and every one, Lois has authored three books—Lois on the Loose, Red Tape and White Knuckles, and Revolutionary Ride—co-founded the Adventure Film Festival with her husband and partner in crime, Austin Vince, and continues to travel as her raison d’etre. She’s just spent a few weeks in Jamaica’s backcountry and has her sights set on Japan.

For our podcast with Lois:

There is an old Persian proverb, Go and wake up your luck, that Lois became familiar with in Turkey while en route to Iran, when a spry, elderly woman bestowed this wish upon her, accompanied by a big smile and throttle-revving gestures. The sentiment resonated, unsurprisingly so, but this also seems to be Lois’ invitation to us, given by example. It’s an ever-present whisper on the dust, in the satisfying hum of the engine, written on the horizon near the clouds: Go on, wake up your luck. If I can do it, so can you.

You prefer a quick and light Yamaha as your bike of choice—it’s practical and gets the job done. How important is your mode of transportation to you?

The way I see it is that the bike is a means to an end—it’s a tool to see the world, a great tool, but as Ted Simon says, “It’s not about the motorcycle.” The reason I like to use a motorcycle for traveling is that it exposes you to everything: the weather, the terrain, the smells around you, both bad and good, impromptu conversations and interactions, and it makes travel a physical experience—you’re engaged. It’s true that I’m not particularly interested in discussing the technical aspects or the finer details of fuel consumption or what tires are best. It’s not that I don’t think these things are relevant—of course, you need to know this stuff to have a successful trip—but for me, they’re not what the story is about, so they don’t end up in my writing unless it is somehow relevant to the story.

Do you do any of your bike modifications or repairs?

Yes, I can do basic maintenance and replace consumable parts such as brake pads, cables, chain/sprockets, oil filters, etcetera. I started out riding vintage Brit BSA bikes which routinely fall apart and conk out, so I had to get used to fixing them and bodging repairs while on the road.

You are different from many motorcyclists in that you travel lo-fi in very normal attire without the latest and greatest accessories and gear. Do you feel this sets you apart, or are you ever criticized for this?

I think there are quite a lot more adventure riders going lo-fi and using smaller bikes these days. It used to be more unusual, but certainly in Europe, I’ve noticed a change in that direction, especially for longer, more gnarly trips where being light and keeping the bike and kit simple is a definite advantage. I have occasionally been gently mocked for my choice of bike, but it tends to be by people who haven’t ridden much beyond the developed world. If you’ve ridden across deserts, through swamps, on smashed-up roads, and tackled cities like Tehran or Kinshasa—or ever had to haul your bike on to the back of a truck or train, or shipped it from continent to continent, you begin to understand why a small bike makes sense. It’s cheaper, lighter, easier to manhandle, and there’s less to go wrong. Also, it’s helpful to have a low-key appearance as it’s easier to blend in, rather than showing up on a big fancy new bike with all the bling—that just creates a division between you and the local people.

One of the reasons you wear an open-face helmet is to let people see your smile first, an invitation to friendship and goodwill. Do you also prefer the style? It’s a little unusual to see these days.

It’s a combination of both. Making eye contact with people and smiling can be a decisive factor in how a potentially tricky situation is going to pan out, for example, at a border crossing, or if stopped by police. Aside from that, open face helmets look much cooler, especially glitter ones. I’m channeling Steve McQueen in On Any Sunday.

What do you consider to be the most essential thing to bring on a venture? Have you ever missed not bringing that fourth pair of knickers? Or anything else for that matter?

Yes, I can definitely get by on three pairs of knickers. Wash them as you go and hang them on the handlebars to dry—that’s always a good conversation starter. With each journey, I take less and less stuff. One thing I didn’t fully appreciate until I’d been on the road a while was that you can get most things you need on a day-to-day basis. Unless you’re heading into a remote desert region for weeks at a time, you will be traveling on roads, through towns and villages where other humans live and are going about their business. And they all need motor oil and shampoo and all the other things of everyday life, so once you realize this, you feel more confident to set off with less stuff and work it out as you go. Of course, there are specific tools that I wouldn’t leave without: just the necessary spanners and sockets, Allen wrenches or hex keys, a Leatherman, and a puncture repair kit including tire levers. And lots of books. The invention of the Kindle has been a lifesaver for me.

You have had some incredibly harrowing experiences in your travels. Has anything ever happened that made you think of throwing in the towel, even ever so briefly? What has been your most challenging experience, and what was your most significant takeaway from it?

I’ve never considered throwing in the towel. Once I’ve made the decision to get out there and do it, then I’ll just keep going— although there have certainly been a few moments when I wished I was at home. In a way, it’s quite a simple way of life, and you get used to dealing with whatever the road throws at you. And the more problems that come your way, the better you get at dealing with them, so in a way, the whole process gets easier. Accidentally straying into a minefield during a huge storm in Angola and then having to ride out, not knowing if my legs would get blown off on the way— that was a bad day. But the reality is that whatever happens, you take stock, and the only response is to keep going.

Real estate in London is ridiculously expensive. But how did you find yourself, at the age of 22, buying and living on a houseboat? This seems like an adventure in and of itself. Your current 1901 house barge is absolutely beautiful, but do you ever pine for a brick and mortar abode with a physical address?

Even then, back in the mid-1990s, property was expensive in London, and I was aware that I would never be able to afford a decent place to live unless I got on the corporate treadmill— and that was never going to happen. So it was partly a practical idea, partly romantic. I love boats, so it made sense to live on one. First I bought a small narrowboat, a traditional British canal boat, and then when I met Austin, we bought a Dutch sailing barge near Amsterdam and brought it back to London. But no, I don’t crave bricks and mortar. Sometimes I would like more space, but we have a separate office and various sheds. I love living surrounded by nature, feeding the swans from our deck and swimming in the river in the summer.

Music is a big part of your life and seems to have shaped you in many ways as well. If you could pick a song to best describe your life thus far, what would it be? At least in its current stage?

I suppose it would have to be an old-timey song originally recorded by the Coon Creek Girls, an all-female Appalachian string band from the 1930s. They did a song called “Banjo-Pickin’ Girl” which includes the lyrics, I’m goin’ round this world, I’m a banjo-picking’ girl…That pretty much sums up how I spend most of my time.

You play banjo in a bluegrass band called The Jolenes. Do you ever take your instrument on the road? If so, does it also lend itself well to the interpersonal relations you seek when on the road?

Carrying a banjo on a motorcycle is a bit awkward, so the only long-distance journey it has accompanied me on is when Austin and I drove a Ural sidecar outfit from Richmond, Virginia, to Seattle, Washington. It was great to have it with me, as we spent a lot of time in the Appalachians, going to jam sessions in Tennessee and Virginia and all around the Blue Ridge Mountains. I have recently been investigating travel banjos which can be taken apart into two pieces. Music is an international language and a great way to meet people and make friends, as long as you’re in tune. One day I would like to do a trip and write a book that incorporates music into its story.

In your TED talk, you talk a lot about letting go of control when on the road. You strike me as a bit of a perfectionist though, albeit one who can relinquish control when needed. Has this ability changed other areas of your life as well?

I do have perfectionist tendencies, which is not always a good thing. It can hold you back from having a go at new things and [also] accepting that you might not be very good at them. So I try to keep this in check, but when it comes to my writing, I like to take a lot of time, thought, and effort over it. I’m not a perfectionist about housework though, so I guess I’m getting the balance right. But with regards to traveling, it can be hard to find the balance between organizing everything so it all goes smoothly, and allowing oneself to go with the flow and enjoy the results. It usually takes me a couple of weeks to reach that stage where I will be relaxed enough to let the trip happen to me, rather than try to control every detail. But that’s when it gets interesting—it’s just a necessary adjustment period, and I recognize it as such now.

You seem to have achieved superstar status in certain circles, particularly the overlanding one. You stay busy giving talks and writing when home, but how hard is it to keep and maintain that fame, which can be crucial when say your occupation is a writer?

Well, I don’t know about superstar, but thanks. Being a freelance travel writer, speaker, and banjo player is a sure way to make sure you won’t get rich. But it’s a lot of fun, and because I’ve been at this game for 15-plus years now, I find that the work finds me most of the time. But it does take a while to get to that position, and it was not always thus. So I’m always appreciative of every opportunity that comes my way, and also always looking for new opportunities and ideas. It’s important to keep adapting.

The Adventure Travel Film Festival continues to grow and prosper, both in London and Australia. You and Austin are both creatives and seem to have found another perfect outlet for your artistic sides. Do you have any other irons in the fire? I’m always looking for new challenges in all areas of my life. Workwise, I am moving into doing more radio/broadcasting, which I love. On a personal level, long-term aims are to learn to sail and to learn Persian, so keep the brain and body moving.

What do you draw your inspiration from? I am assuming it comes from all sorts of things, given that your initiative to ride to Iran began with a random note left on your motorbike in London by a man named Habib.

Inspiration can come from all sorts of places. The desire to seek out specific aspects of a country such as the local music or architecture, or simply curiosity—to go to a place I’ve never been with a culture totally different from my own. Sometimes it comes from reading a novel or watching a film set in a particular part of the world. I don’t need much of an excuse.

Do you have any mentors?

I don’t have any specific mentors, but I did seek out people for advice before I set off on my first long-distance motorcycle caper from Alaska to Argentina, including my now-husband, Austin Vince, who had motorcycled around the world for his film Mondo Enduro. That is how we met, because he was giving me advice about my trip— then one thing led to another. I also spoke to a British woman called Sarah Crofts who had made a similar journey. She gave me an excellent piece of advice which I now pass on to others. She said: “It’s so much easier than you think it’s going to be.” That one sentence gave me so much hope. It sounds simple, but she was absolutely right.

Chris Scott’s Adventure Motorcycling Handbook had a great effect on me too; it’s so much more than an instruction manual. Chris’ writing style and approach are both practical and straightforward but very human and funny. I used to read the AMH compulsively when I first got the idea of doing a motorcycle trip; it showed me that anyone can have a motorcycle adventure, you don’t have to be a superhuman. Your book Revolutionary Ride is an exquisite tale of jumping in headfirst to a culture completely different from your own. Do you ever find that recording the adventure gets in the way of the experience itself? One of the beauties of writing, as opposed to film-making, or even photography, is that it is all going on in your head quietly. It never interferes with the experience. I spend a lot of time while riding thinking about how I’m going to write up certain scenes, and then at night, I always write longhand in my diary, no matter how tired, cold, or wet I am. It’s crucial to get everything down on the page that day while it’s still raw.

British travel author and explorer Freya Stark and her books figured prominently in your travels to Iran. You even end Revolutionary Ride with a quote from her on the reason to travel: “To feel, and think, and learn—learn always, surely that is being alive.” Other than travel, what else makes you feel most alive?

I’m a sociable person, so being around great people, good conversation, and laughing a lot—those are probably my favorite things. That’s why I enjoyed being in Iran so much because the Iranians are fun, witty, and engaging people. But apart from that, I feel alive in nature, and particularly on or in the water, whether it’s the river where I live or a great ocean, I love to swim, kayak, or be on any kind of boat. Water is very important to me, and if I’m away from it for too long, I get withdrawal symptoms. I also get a buzz from creative work, so from writing, when it’s going well, and playing and listening to music too.

You’ve credited your parents in teaching you not to be afraid of anything. Has it ever backfired? Or was this the best lesson of all?

I believe it’s a critical lesson that has served me well. I’m not reckless, and I’m not an adrenaline junkie, but I like to try new things and challenge myself. And although I do feel fear, I don’t let it put me off from having a go at things.

From Revolutionary Ride, “You can tell a lot about a person by how they give directions…” How do you give directions? I like to draw a little map.

Do you have any advice for those looking to begin a life of adventure by travel?

You need to believe that you can cope with any outcome, and this belief can only be created with evidence-based on previous life experiences. So if you’re worried, start small and build up this belief until you find yourself feeling that you can do anything. This is how you can consciously build confidence. To have a great life of adventure, you don’t have to be an athlete, a millionaire, multi-lingual, a super dirt-rider, mechanic, or anyone out of the ordinary. Optimism, flexibility, and an open mind are far more important characteristics.

BIBLIOTHECA

Lois on the Loose – Written after Lois left her job at the BBC to pursue a career in wanderlust, it chronicles her adventures traveling from the northernmost point in Alaska to Tierra del Fuego.

Red Tape and White Knuckles – A fascinating tale of the 10,000-mile jaunt Lois took through Africa. With the bones of an action adventure story driven by the straightforward narrative of a bold, globetrotting heroine, it is an uplifting take on throwing caution to the wind.

Revolutionary Ride – Her latest book (and the one Lois is most proud of) takes adventuring to another level by digging deep into our motivations for travel and exploring the inner workings of Iran and the people that make it tick.

Youtube: