“Maybe you shouldn’t go. It has just snowed for the first time this year. Samui!” our hosts said.

“Ah, a bit of snow. It can’t be that bad,” I answered, not wanting to be discouraged from my plan. I wanted to go on a hike in Shiratani Unsuikyo National Park on Yakushima Island. It would be a welcome break from 3 weeks toiling on the Land Cruiser that was getting an unusual amount of TLC at 4Friendee Auto in Kagoshima.

“Why go there? We will need our time.” Coen argued, who was the one who did the toiling with Mr. Nakashima and the mechanics.

“Yeah, you’re right. But, well, you know—my eyes keep straying there.”

During our 15 years on the road, Coen has learned that this pretty much means that we’re going.

Over those the years of traveling and studying maps, I have learned an important thing: I pay close attention to places on the map that my eyes keep being drawn to. Interestingly, in most cases, there is nothing of note—at least according to guidebooks and tourist information centers. Reality, however, has taught me otherwise. There is beauty everywhere although it may require time, patience and a mindset to find it. In Japan, my eyes stayed glued to Yakushima Island, which was remote but drew its fair share of travelers as its national park was a UNESCO site. When I did a Google search, the photos of the forest blew me away. We had to go!

On Our Way

Samui! It was one of the first words we learned in Japan: cold. And cold it was. Hoar frost shimmered over harvested fields, announcing the first night of frosts in southern Kyushu as our hosts drove us to the ferry in Kagoshima. The blue sky promised a beautiful day, and the 4-hour ferry crossing was relaxed. On arrival, we stopped at a small restaurant and savored a meal of tanuki udon noodles with greens. An hour later we were on a bus, left the coast, and snaked into the mountains to the entrance of the park.

“Here you have to get off,” the bus driver indicated. We took out our walking sticks, hoisted our backpacks and headed for the trail, excited to find out what lay ahead of us. Within a couple of minutes we were engulfed by the forest. Most of the primary forest had been cut in the 18th and 19th centuries and been replaced by secondary forest, but a few trees had survived the onslaught. The handful of Yagoi-sugi cedars, hundreds of years old, were humongous and demanded respect. The trail, sometimes provided with stairs built of wood, cut through the vegetation. It wove around trees, wide, heavy, aerial roots, and vines and boulders covered in moss. With the afternoon light filtering through the foliage, the terrain and atmosphere created a fairy-tale kind of forest—inviting, innocent, beautiful, yet with a who-knows-what’s-behind-that-corner feel, like in a Lord of the Rings movie. Even though most trees were young the landscape felt old and magical. The density of the forest demanded the trees to work hard to survive. To reach the sun, many were twisted in the weirdest shapes with trunks and roots intertwining, or one trunk splitting into multiple trees.

By the time we reached our shelter, the sun had disappeared behind the mountains and temperatures plummeted. We put on all our clothes, including woolen hats, but lacking winter jackets we had brought our rain jackets. The hut was an ugly concrete structure but served us well. In Japanese houses, you take off your shoes before entering and here it was no different. In the center was a wooden platform, for socks only; shoes stayed on the concrete floor. According to the guestbook it was busy in July/August, but during the rest of the year this shelter was not much visited, least of all in December. The one other visitor hid himself in one of the four rooms with bunk beds and was not interested in socializing.

Into the Snow

Two beautiful days followed. Cold at night and in the mornings, but quickly warming up once we stepped outside into the sun and hiked, mostly uphill. The viewpoint of Talk-Iwa Rock at 1,050 meters looked out over a valley, the first snow-covered ridge in the distance and a winding river deep, deep below. Part of the trail on day 2 consisted of an abandoned railroad track that had been used for dozens of years to transport timber to the coast. It was an easy to follow the trail as we enjoyed the rhythm of our steps with the sound of the river in the distance.

Once we hit the snow, the real work began. Rocks became slippery and as the dark soil disappeared underneath a layer of white, we watched our every step. On day 3 we got into more serious snow hiking. With the trail often invisible, our feet and legs often slid off the side, deep into the white powder. We left the forest below us and climbed higher to the top of the mountain with views of slopes covered in thick snow. Under the clear blue sky, the sun beat down on us. We stripped down to our shirts and sweated with the effort of our climb. While monkeys retreat to the warm coast in winter, Yaku deer didn’t seem to be bothered at all by the snow. The small deer were easy to spot and not afraid of our presence. We could approach them to within a few meters. Some followed us with what seemed a curious look, others continued their search for something to eat.

What a privilege to be here! At times, the ongoing destruction of the planet depresses and frustrates me. To be in the wilderness, to be part of the wild that still exists and thankfully is protected, lifted me up and gave me energy. If only everybody was able and willing to spend some time in surroundings like these, to truly feel, see and sense to the core how mind-blowing, inspiring, and energizing it is! Maybe then we’d all be working together to save the planet.

The Last Push

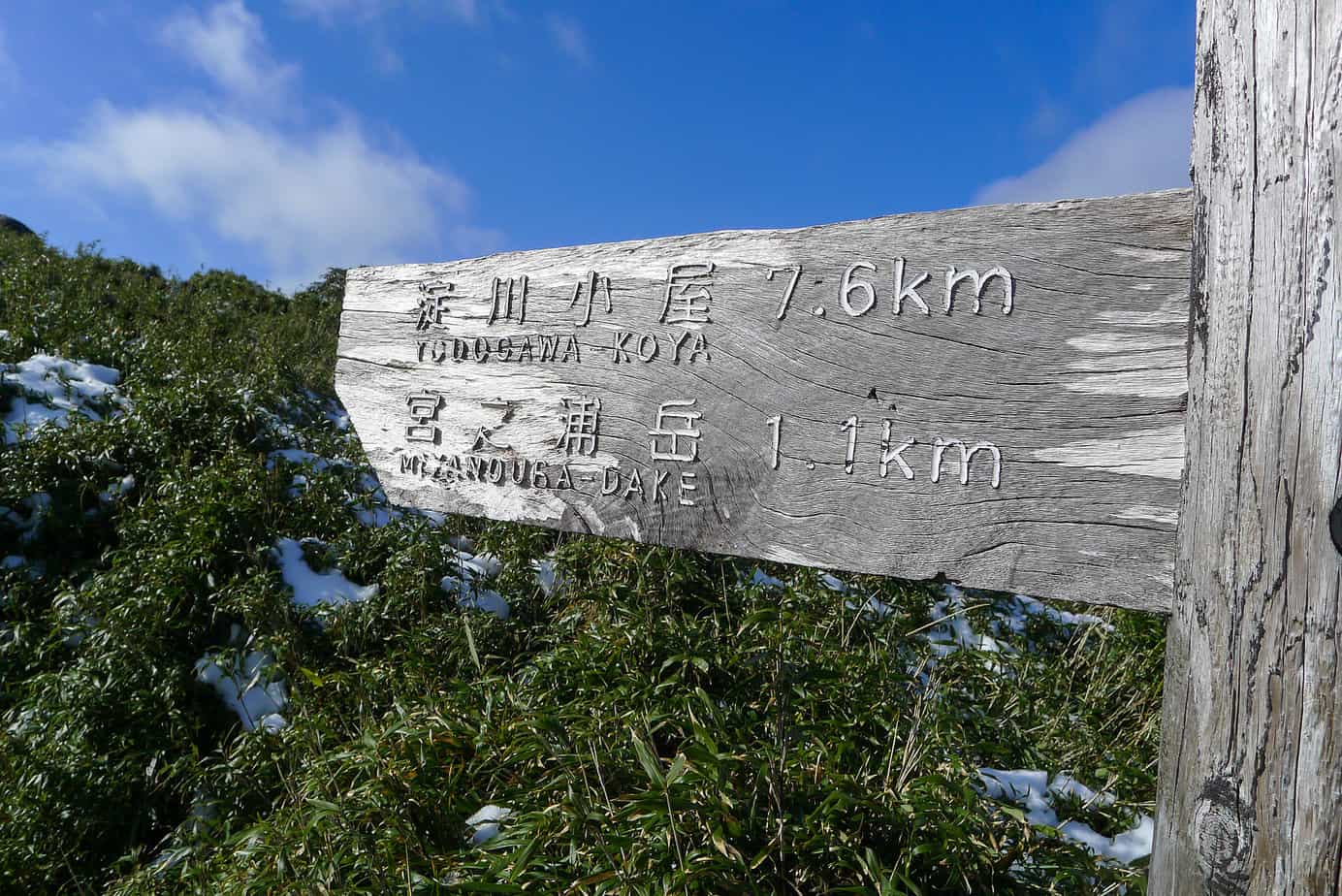

On a bare rock we sat down, took out our MSR stove and cooked our twice-a-day hiker’s dish of noodles with seaweed and mushrooms while we nibbled on a piece of dried fish with sesame seed. We lingered in the warming rays of the sun. Could we stay here forever, please? Rather than taking the same route back, we hoped and anticipated that there would be less snow on the other side of the 1,936-meter high Miyanouradake Mountain. I have no memory on what kind of argument we based this assumption, but in retrospect it was a misguided notion of two people who come from a flat country with little snow. We clearly don’t have a clue what the combination of mountains and snow can do.

For hours we fought our way down through thigh-deep snow, initially exhilarating, under a blue sky and going fast. We splashed through ice-cold streams and pulled ourselves up using branches and rocks. This stretch included a higher level of clambering than we had done thus far, and we loved it, but as the sun went down, we started to slip, fall, and hurt ourselves as we were pushing to get to the shelter before dark. Yet, being there was magical. We were all by ourselves amidst hills covered in cedar or deciduous trees, in the distance still displaying beautiful autumn colors. Other hills with vertical walls were covered in ice.

If only the day had had more hours of light so we could have taken it slower, including more stops to enjoy views. However, darkness fell. For an hour we hiked with our headlights on. To say we were relieved to reach the shelter is an understatement. I didn’t even register whether it was made of concrete or wood, whether it was beautiful or ugly. It was empty and protected us from the elements, no matter how cold it was inside. We put on all our clothes and cooked while wrapped in our sleeping bags. While we were having a restless night, the weather gods debated and concluded there had been enough snow. When we woke up it was raining.

It was a short hike out of the forest, onto an asphalted road, where we took a bus to town for a decent meal. Yakushima has an interesting climate: high in the national park it can get as cold as on Hokkaido Island in the far north while along the coast—and that’s a two-hour ride, at most—the weather is as mild and subtropical as on Okinawa. As the weather cleared, we hitchhiked to the other side of the island to one of the most awe-inspiring onsens in this country. During low tide a circle of stones appears above the surface, marking a hot spring. Soaking up the heat with a view of the ocean and a fabulous sunset, we felt the luckiest persons in the world to be here.