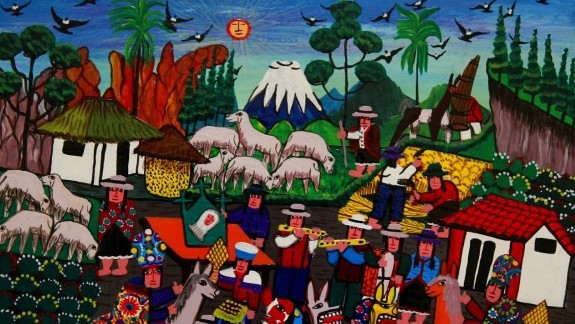

In Ecuador I bought a painting. It was a messy chaotic scene.

In Argentina, a similar style painting would go something like this: a flat sheet of desert surrounded by snowcapped peaks. Grapes droop from a tangle of vines in one corner. Stray dogs happily run in packs down the street. In the hills gauchos ride their horses, checking the fence lines and rounding up sheep.

In another corner of the painting, siesta time is taking place. The streets are desolate and the stores are closed, with the exception of ice cream shops. People wander, licking their dulce de leche ice cream. Acquaintances meet in the street, greeting each other with a kiss on the cheek. The women all have long beautiful hair, reaching the lower vertebrae of their backbone. Men fashion long hair as well, pulling the tangle of hair high in a bun on top of their heads. In a grassy field, families cluster around an asado. The grill is stacked to capacity with ribs, bife de lomo, legs of lamb, and links of blood sausage. Bottles of Merlot sit like table centerpieces. Long after the families are gone, smoke rings linger in the air.

Brad and Sheena are driving around the world in “Nacho”, their Volkswagen Vanagon. Read their stories and follow their adventure at Drive Nacho Drive [link]

Alongside the grassy fields, bushes of orange flowers and stalks of purple dragonflies border the road. In a tree, red flags and ribbon hang, symbolizing yet another Gauchito Gil shrine. Down by the river, fishermen’s rods drip with trout. Mate gourds are cupped in every set of hands. Staying high on life, they sip their bitter tea from sun up to sun down.

Argentina: it was all rainbows and unicorns. Culturally, it came as a surprise as it was vastly different from its neighboring countries. The metamorphosis of culture, facial features, and cuisines that consistently took place from one neighboring country to the next ended abruptly here. Goodbye rice and potatoes. Hello wine and meat.

A short presentation of Argentina’s cultural uniqueness…

Gauchito Gil, the cowboy saint

I met the most famous saint in all of Argentina for the first time in the desert along the Ruta 40. The landscape was bare all around, yet under a mature tree, red flags, strips of fabric, and artificial flowers were strewn throughout the tree branches, announcing his presence. He sat under an arch painted in a matching red. He wore his hair long, slightly wavy with a matching wispy mustache. His blue long sleeve was pushed up to his elbows and a red scarf tied around his neck. He was five inches tall and made of a hard plastic.

While the real Gauchito Gil, a.k.a. Antonio Mamerto Gil Núñez, died in 1878, shrines of him number in the thousands. As the story goes, he was an outlaw who became a symbol of bravery, stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. Today, many people stop at the roadside shrines, giving thanks to Gauchito by leaving offerings such as water bottles, jewelry, car bumpers, and scraps of clothing. We on the other hand stopped at his shrines, using them as an excuse to stretch our legs and explore the offerings. Always colorful, always unique and intriguing.

While most shrines were dedicated to Gauchito Gil, there were others. The next most interesting were shrines for Deolinda Correa who in the 1940s set out into the desert with her infant baby, in search of her husband who was forcibly taken to join the military. She died in the desert, but as she lay down, dying of thirst, she set her baby to her nipple, who survived until her body was found by gauchos. The gauchos took in the child, raisings him on the plains driving cattle. Now, Argentineans leave bottles of water at her alters to “calm her eternal thirst”.

Siesta

Argentineans are serious about siesta time. Beginning at 1 pm all businesses shut down. Grocery stores. Banks. Retail shops. Police stations. All until 5pm, Monday through Friday. The only exception here (that I noticed anyway) is ice cream shops. Always open. Always there to serve. You can only imagine how serious Argentineans are about their time off on the weekends and holidays.

And what is it like in a city where everyone is on siesta? Runners take over the sidewalks and friends ride down the street on their bikes. Young crowds sit in the town square and drink mate, and older couples rest on park benches, watching the day go by. As much as the siesta frustrated us as travelers, we could see its benefits, forcing people to focus on themselves and their relationships; a generous break from the commercial aspects of the everyday world.

Late night dinners

Dinner starts at 9:30 and many restaurants don’t open their doors until 8:30. It is not uncommon to finish dinner in the early morning hours. I wondered for quite some time if it meant that Argentineans woke up late, yet they do not. They are at work by 8 am, with little breakfast and littler sleep.

Desert oases: where wine really flows like water

Argentina’s wine regions are located within the broad valleys and sloping plains of the desert, creating oases ideal conditions for grape cultivation. Our first wine destination was in Cafayate, known for their dry white Torrontes. Day one was a success, checking off five of the six estancias which offered tastings and were within walking distance from the town square. As we continued South through Mendoza, the most important wine region in Argentina, vineyards and estancias flooded the outskirts of the city. And the wine was so incredibly cheap and plentiful. Between touring wineries, we stopped in at other establishments, such as Simone’s Olive Oil where the owner took us through his variety of olive oils, soaking cubes of bread in bowls of olive oils, tasting the varieties and their different qualities.

As for the wineries, most offered tours of the facilities and explanations of their processes. For example, what a house wine is and why it is more affordable? Simply put, wine is made through a period of aging. With more time, more flavor develops. During the life of the fermented grapes, portions of the liquid in the vats are drained. The first round of draining occurs just days after the start of the fermentation process, and this liquid is used to make a house wine. And as the fermentation time is short, the wine is not fully developed, lacking in the body and color that most people look for in a wine. This is the difference between most house wines and regular bottles, and explains why we can get house wine with our asado for only a couple of dollars.

Gauchos, Asados and 55 million cattle

In the 1500′s, Spain drastically influenced Argentina’s culture with the importation of cows. Today, Argentine beef is world famous. All we ever heard from every traveler who had made it to Argentina before us was “Oh just wait until you get to Argentina! The beef there is soooo good. You can get a steak the size of your plate and 4 inches thick!” Was it really true? Could it be?

Just a few blocks down from the main square in Cafayate, under the tall trees shading the walkway and beside the red umbrellas, a chalkboard advertised a parrilla completa for two. Inside the focal point of the restaurant was the massive grill stretched across the length of the restaurant. Atop were chunks of steak, chicken, chorizo, sausage, and ribs. We enjoyed a very meaty meal, with coals under our table top grill to keep the food warm and tender. Argentine meat was insanely good and for the next week, we ate at a parrilla every day, attempting to satisfy our incessant craving for Argentine meat.

More food culture

At a roadside stand a family worked together in an assembly line, scooping a meat filling into the center of sheets of dough, folding them over, and pinching them closed. In a wood fired ovens, dozens of dough balls went in. What came out was Argentina’s most famous street food: the empanada. This became Brad’s favorite food. It was easy to find. Every bakery, restaurant, and gas station offered their own version. My favorite? Locro soup. A warm creamy concoction of hominy, squash, spices, and chunks of stewed beef shoulder. Do yourself a favor and save this recipe for a rainy day.

Smitten for yerba mate

Everywhere we went, people drank mate. In the park, groups of friends sat in circles sharing a single vessel of yerba mate. In the stores, employees sipped their mate as tourists browsed their merchandise. On the bus, commuters poured water from their thermoses into their gourds. Over and over again. Argentineans only carry on their daily business if a mate is in hand.

The drinking of yerba mate involves a host and one or more people, beginning with the preparation of the drink. The host packs the yerba (the herb) into the mate (the vessel used for holding the tea – usually a hollowed out gourd) and once tightly packed, the bombilla (metal filtered straw) is arranged to sit firmly upright in the tea. Lastly, warm water is poured into the mate and passed to the first participating drinker. Customs as a participating drinker are to never touch the bombilla with your fingers and to drink all liquid in the mate before passing it back to the host. And it must always go back to the host. ‘Thank you’ is only whispered when you’ve had enough and are bowing out of the tea time rotation.

Interestingly, while yerba mate is insanely popular, it isn’t often a part of the tourist experience and it is not served in restaurants due to its tedious preparation process and commonality as a daily ritual.

What does it taste like? Just try to imagine the incredible tart and bitterness of a liquid produced by stuffing 10 tea bags into a single serving cup. This stuff is STRONG. We wanted to love it, but I think you have to have a little Argentina in your blood.