Journal Entry

October 9, 2005, journal entry by Mark Stephens 33º17’24”N, 109º15’25”W

When the Jeep stopped moving, I had a hunch we were in trouble. I tried to restart it, but I knew better— I knew exactly what a dead fuel pump felt like. It was a little pointless hope, but hope was all we had—since Brooke and I were totally alone, and over 40 miles from the nearest town, on a solitary road that went nowhere.

Based on the GPS, we knew we had at least a 10-mile hike to reach the nearest residence. While we hiked, it rained. Then it hailed. Then it rained harder. The only option we had was to keep walking, since we were limited to the food and water we carried.

And after those 10 miles? A ranch house, complete with chickens, horses, dogs, and a Ford pickup, yet no one was home. We were soaked, cold, out of water, but had two containers of yogurt and a half-package of beef jerky—a blessing? I felt like a criminal poaching a night’s bivouac in the dusty bunkhouse while the owners were away, but surely there was nothing else to do in that weather.

We finished our rations the following day while making the push toward the highway, another 18 miles away. We removed our shoes, hiked up our pants, and waded across the Blue River. At least it was sunny. The thing we never spoke about, but kept thinking to ourselves, was, “What if we don’t find help today?”

It was early in the afternoon when we came upon another ranch; this time with a person. Sharon was her name, a kind cowgirl who sniffed out that we were in trouble from a hundred yards away. “Oh my God, what happened to you?” she asked.

Sharon’s ranch was still about 40 miles from town, so she let us make a call with her cell phone, with which I made short, spotty contact with my family and managed to pass off our coordinates. We’d made it.

Preparing and training to survive unexpected and challenging incidents is not just the realm of men and women in uniform. It is an essential exercise in self-reliance and preservation for the overland traveler. Mark’s story came to a happy ending because he and Brooke are exceptionally fit and could travel quickly, and had a good sense of where help and shelter would be located. However, with a few additional pieces of equipment they could have communicated their problem to the outside world, set up effective shelter, and remained dry, warm, well-fed, and hydrated. One way to ensure this equipment is always available is to carry what sailors call (for obvious reasons) a ditch bag. But with all the gear and food we already carry in our vehicles, why should a separate ditch bag be necessary?

The goal of a ditch bag is to have a self-contained, life-sustaining kit instantly accessible to the driver. Its sole purpose is to ensure comfort and survival should the occupants be required to evacuate or abandon the vehicle. Evacuation can happen for any number of reasons; common would be a vehicle fire, a failed water crossing resulting in hydrolock of the engine in a dangerous current, or breaking through ice over deep water. Abandonment is less abrupt, due usually to a non-repairable breakdown or a non-recoverable stuck vehicle, when for some reason contact cannot be made with rescuers and passersby are extremely unlikely (such as the situation faced by Brooke and Mark). Much more time is available to retrieve supplies from the vehicle; nevertheless, having a basic kit already prepared puts you a step ahead.

Here are the four critical requirements:

1 – Prevention

Risk is often unavoidable during an expedition, but that risk must always be balanced with preparation and good judgment. Keeping an accessible ditch bag in the vehicle is wise; leaving it forever unused should be your goal. Know the thickness of ice and the depth of rivers, and make every effort to prevent disaster from occurring in the first place. Make an effort to travel with multiple vehicles. However, accidents do happen, plans fail, we take solo vehicle trips, and unforeseen dangers can result in you being completely separated from your vehicle.

2 – Communications

You must be able to communicate your need for assistance. The best way to resolve a vehicle separation incident is to have a method of summoning rescue. If you are 200 miles from help, the meager rations and water you have in the ditch bag will only last for three to seven days (possibly a bit longer, depending on environmental conditions). You might be injured and unable to trek. The goal is to plan for the worst eventuality, and the best chance for rescue is to be able to call the authorities or trained personnel and organize a recovery. There are a few effective ways to do this:

- Satellite phone: Immediate voice communications anywhere in the world (depending on the system) should rescue or medical evacuation of yourself or other occupants be required.

- Personal Locator Beacon (PLB): Typically uses 406 MHz to transmit the unit’s unique digitally-coded signal (used to identify the person being rescued and any known medical conditions, contact persons, etc.) via GEOSTAR and other satellite systems. Most units also transmit a 121.5-MHz homing frequency.

- SPOT satellite messenger system, which uses a combination of GPS and communication satellites to transmit emergency and basic update and tracking messages. The one clear advantage of the SPOT over a PLB is the ability to send a “help” message to friends and fellow travelers, when you require assistance but not emergency evacuation. SPOT also allows general “I’m okay” check-in messages, as well as immediate 9-1-1 emergency contact.

3 – Shelter

Once any medical emergencies have been stabilized and the call for assistance has been initiated, it is critical that everyone has adequate shelter from dangerous environmental conditions, which can include rain, snow, extreme cold, extreme heat, sun exposure, etc. If possible, stay near the abandoned vehicle (even if it is just a burned-out hull), since a vehicle is much easier than a person to spot from the air.

In a survival situation, you’re not concerned with comfort, simply protection from exposure, so forgo the weight of a heavy tent and use an ultralightweight tent or bivvy. Make sure the sleeping bag you have packed has an extreme temperature rating to suit your expected conditions. My kit typically includes a compact, 20-degree Big Agnes bag with a lightweight, insulated pad. Both the pad and bag are insulated with PrimaLoft, which retains much of its insulative properties when wet. Additionally, my kit includes a heavy-duty space blanket, which can be used as a tarp, and an Adventure Medical Kits 2.0 Bivvy Bag, which adds a bit of warmth to the sleeping system and additional weather protection. In warmer environments I can eliminate the sleeping bag and pad and carry just the bivvy and blanket .

4 – Water and Food

Once communications have been established, and shelter from the elements is resolved, your situation becomes a waiting game. With help on the way, staying calm, dry, hydrated, and well-fed is your priority. Even just a few warm meals and a hot chocolate can do a great deal for morale.

On the other hand, if for whatever reason you have not been able to summon help and are faced with a hike out, food and water become even more important. There are many variables that affect when and if you should leave a vehicle and walk for help, but should the need arise, you must have sufficient water and high-calorie foods available. Meals should be either ready to eat or require an absolute minimum of preparation.

Renew, Inspect, and—Don’t Mess With It

Once you have determined the contents of your kit and you have stocked it with the required gear, don’t mess with it. Other than a periodic inspection, and renewal of perishable items, the kit should stay with you, in whatever vehicle you are driving (even for that “short” day trip to the mountains), and remain unmolested unless a genuine emergency arises. Don’t use the multi-tool or flashlight or matches for day-to-day needs, and don’t snack on the MREs.

Planning, education (medical and survival training), and prevention are the keys to surviving a vehicle separation incident. Overlanding takes the traveler to remote, challenging and unpredictable environments. Preparation, communicating your route plans, and having a properly outiftted ditch bag can make the difference between an epic adventure story and a eulogy. Be prepared!

24 Hour Survival Test

After assembling what seemed to be a solid complement of ditch bag contents, Overland Journal’s editorial director Chris Marzonie and I decided to test the ditch bag in a real-world scenario. Several other Overland Journal readers came along for a trail run on a snow-covered route just south of Prescott, Arizona. To make it as realistic as possible, I only wore standard clothing and light boots. My goal was to spend the night in the forest with the ditch bag and trek 11 miles into Prescott the next morning. For additional safety, I carried a 2-meter VHF radio. Here is the timeline.

- 9:00 a.m. Leave for trail-run in the Bradshaw Mountains. Forecast calls for snow; 12 to14 inches already accumulated.

- 12:00 p.m. We reach our most remote location on the trail, and eat lunch.

- 4:30 p.m. Simulated vehicle fire. I grab the ditch bag in about seven seconds, and retreat 10 to 15 yards from the Tacoma. I transmit an “OK” with the SPOT device.

- 5:00 p.m. The sun is setting and I have added all available layers of clothing from the ditch bag, plus what I grabbed from the truck. I am wearing Montrail waterproof mid-height boots, canvas pants, and an Ex Officio base layer and long-sleeve BUZZ OFF shirt. My jacket is a parka with liner, the same one I used for much of the Arctic Ocean expedition (see Overland Journal, Winter 2007).

- 5:15 p.m. The group leaves down the trail and I am alone. The forest is silent.

- 6:00 p.m. The available light is nearly gone and I must cross the Hassayampa River, which is fortunately low enough that I can hop from rock to rock. Reaching the northern shore, I begin the trek north towards town.

- 6:30 p.m. I am nearly at the highest point of the trek, and find a shallow draw with good protection from the wind, some tall grass, and less snow cover. I set up the bag, bivvy, and pad.

- 7:30 p.m. The cold is coming quickly and I start a small fire with the Ultimate Survival Technologies ignitor, flint, and Wetfire tinder. It starts immediately, but is difficult to tend and maintain, since much of the available fuel is wet. I send another SPOT “OK,” which we find out later does not transmit successfully, probably because of the heavy tree cover.

- 8:00 p.m. I eat a dehydrated meal and have a hot chocolate. My feet are cold, so I retreat to the sleeping bag after extinguishing the fire.

- 8:30 p.m. Comfortable, perhaps even a bit too warm in the bag, I remove the parka and use it as a pillow. The temperature is 25°F.

- 2:00 a.m. I awake and my feet are a little cold, but it is only a slight discomfort. The temperature reads 18°F. I note that the Big Anges inflatable pad is “comfy.” I fall back asleep.

- 6:30 a.m. I am up with first light and make a hearty breakfast to support the trek. I take quite a bit of time packing the bag and removing all evidence of the small fire and my remote camp. I transmit another SPOT “OK,” which is received by Chris.

- 8:15 a.m. I hit the first main road north and pick up the pace. The day pack is okay for trekking, but has insufficient hip support.

- 11:15 a.m. Prescott comes into view.

- 12:00 p.m. I walk into the Prescott Brewing Company to see Chris, Christophe, and my wife Stephanie all smiling at me. They hand me a big, cold Coke. Life is good and I am no worse for wear.

Contents (not including food):

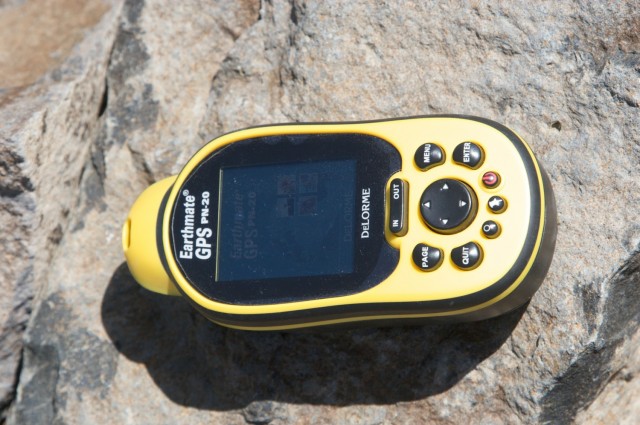

- DeLorme PN20 GPS

- SureFire L1 LumaMax flashlight

- Hard candy

- Water purification

- Compass

- Notepad/pencil/pen

- Map, coordinates list

- Blister kit

- Medications

- Signal mirror

- Lighter (Brunton Helios)

- Adventure Medical Kits Trail first aid kit, blood stopper dressing

- Adventure Medical Kits Thermo-Lite 2.0 Bivvy

- Stove (Snow Peak Giga Power titanium)

- Headlamp (Black Diamond)

- GPS (back-up) Delorme PN-20, extra batteries

- Documents (copy of passport and drivers license)

- Cash ($60, small bills, stashed in several locations)

- SPOT and extra batteries

- Respirator

- Mechanix gloves

- Poncho

- Electrolyte drink packages (10)

- Sunscreen

- MSR Dromedary Bag

- Sunglasses (polycarbonate lenses double as safety glasses)

- Ex Officio bandana

- Ex Officio desert hat

- CRKT Zilla Tool

- U-dig-it Trowel/shovel and toilet paper

- Strobe light

- Parachute cord

- Socks

Bug Out Bagz, Bill Burke Edition $365

Bill Burke is an accomplished 4WD trainer and Camel Trophy participant who worked with Bug Out Bagz in Tempe, Arizona, to create a turn-key ditch bag that contains the majority of the items required for survival. They also sent Overland Journal a kit to test, and I found the quality of the components to be good or excellent. I would trade the hygiene kit (comb, toothpaste, etc.) for the AMK 2.0 Bivvy, since no notable shelter is included in the kit. Based on our recommendation, the company now offers the 2.0 Bivvy shelter as an option.

Here are the contents of the Bug Out Bagz kit:

- Deluxe back pack by Stahlsac (19.5 x 11.5 x 6.5 inches)

- Personal first aid kit

- Personal amenity kit

- Victorinox Swiss Army Rescue Tool

- Pelican Products MityLite 2300 flashlight

- Heatsheet blanket (56 x 84 inches)

- Yellow rain poncho (10 mil PVC)

- Esbit Pocket Stove with 6 large solid fuel cubes

- Superwinch heavy-duty work gloves with 2.5-inch cuffs

- Particulate N95 respirator (x2)

- Sqwincher “Lite” Qwik Stik electrolyte drink mix (x4)

- Plastic bag kit

- Diamond strike-anywhere matches

- Rapid Cold (5-1/2 x 10 inches)

- Rapid Heat (5-1/2 x 10 inches)

- MicroNet microfiber towel (10 x 20 inches)

- MAX ear plugs

- Cactus Juice Sun & Skin outdoor protectant (2.5 oz)

- Ztek indoor/outdoor mirror safety glasses

- Pocket survival pack (Including Fox 40 micro whistle and signal mirror)

- Netline flexible clothesline & utility cord

- Laerdal CPR barrier pocket mask w/gloves and wipe in hard case

- Dental Medic kit

- Buck Tilton’s Backcountry First Aid and Extended Care (5th Edition)

- Backpacker’s trowel

- MSR CloudLiner three-liter hydration bag

- Bamboo compressed towelettes (10 pack)