Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal, and updated slightly with recent information.

It was dark, but I could still see the sheen of the soldier’s gun. He was yelling at me in Russian and pulling my camera from inside the tent. Just moments earlier a van had rammed the border fence, several drunk travelers spilling from its confines, laughing at first and then coming to terms with the scene; soldiers with guns and a commander yelling at the top of his lungs. We were between Mongolia and Russia, inside one of the longest no-man’s lands in the world; our hosts were far from pleased. The hour was 1 a.m., it was freezing cold, and condensation from each breath, now elevated to an excited rate, rose into the Mongolian night. Vodka, the regional drink of choice, had been flowing on both sides of the conflict: I was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Imagine travel during the Mongol Empire, when most of the known world was controlled by a single entity. Passage across borders was granted by governance only, or attempted illegally. The first known reference of granted passage is found in the Hebrew Bible (Nehemiah 2:7-9) when the Persian King Artaxerxes provided to Nehemiah, “letters to the governors of Trans-Euphrates, so that they will provide me safe-conduct until I arrive in Judah.” Letters granting safe passage were common in that era. Though passports and visas are usually all that are required, there are areas of the world where offers of safe passage from a chieftain, or introduction documents from officials or ministries, still have relevance.

The issuance and use of a passport is approximately six centuries old. Initiated during the reign of Henry V of England, the document would include a detailed description of the carrier and allow freedom of movement and commerce between France and the recently United Kingdom. In 1920, the League of Nations agreed on the basic format and construct of the modern passport. Detailed descriptions gave way to photographs and a standardized design amongst issuing nations.

From the perspective of an overland traveler, the passport is the ticket to exploration beyond our native borders, and a surprising number of Americans have one (42% as of 2018). This is certainly not to say that overland travel must be done in foreign countries, but the sense of adventure and discovery increases considerably once we leave the familiarity and protection of our own borders.

That night at the Mongolian border taught me a few important lessons; the most important of which is that honesty and a smile will calm most nerves and produce a completely different result than deception and frustration. I ended up getting my camera back and we headed off on the dusty northern route. Within a few miles, we came across the van; its very drunk occupants had rolled the vehicle in a gravelly turn.

Before You Leave

A little planning and research prior to an intended border crossing will increase your chances of success. Start by communicating with travelers who have recent experience in the regions. Online communities like ADV Rider, Expedition Portal and the HUBB are excellent places to start. These sites can often yield more current information than the State Department can provide, as does WikiOverland. Use caution on the forums and social media groups that emphasize the “lifestyle” over bumps, bruises, and passport stamps from the real world. We have found this to be invaluable, and using them has, at times, resulted in significant changes in our routes: our entry into Russia and Kyrgyzstan in particular. Here are a few subjects I’ve found to be good starting points for research:

Best crossing location: There are often secondary, or truck/ commerce crossings that are more pleasant and less crowded. However, they usually have limited hours of operation and may be ill prepared to deal with tourists.

Unique requirements: Each country has its own special process for entering or exiting. Knowing this information ahead of time will greatly improve efficiency and reduce potential issues.

Restricted items: Many countries do not allow importing or exporting large amounts of fuel or cash; and a pile of camera equipment may also raise suspicions. Most important though, are there any restrictions on satellite phones, BGAN units or other radio frequency devices? Know the laws before you go.

Importing or exporting food products: I know how disappointing it can be to toss out a hundred dollars worth of food that was just purchased. Often, these restrictions are in place to control the movement of non-native species and diseases; these requests should be respected. Fruit is almost always a no-no, meat and dairy is often off limits, and some of the restrictions can be quite humorous. For example, a ban on chicharones coming from Mexico to Belize (chicharones is fried pig skin, usually complete with dripping grease and hair).

Visas

With any international overland adventure, you need to determine the visa requirements for each country on your itinerary. A visa is an entry document, typically obtained in advance, where the host country pre-authorizes your entry. They vary widely and often the requirement depends on the country of origin of the applicant. For example, Mongolia does not require a visa for American citizens, but they do require one for someone from England (and most other countries). For U.S. citizens, the most reliable source for this information is the Department of State. Based on the itinerary and duration of the trip, it is common to secure all visas before leaving home. This can be done using a visa service company, or by personally visiting the destination country’s consular offices (visa by mail is also possible). A visa service will charge a fee, but they are exceptionally efficient and know all of the bureaucracies involved in the process. However, on very long or loosely planned trips, obtaining the visas beforehand will not be practical. In this case, securing your visa will need to be done en route, most often in the capital city of the neighboring country.

For nearly all of the countries in the Americas, visas can be obtained right at the border, eliminating any need for travel-window estimates, extensive applications, or long wait times. For almost all countries of Central Asia and Africa, a visa will be required in advance of entering. Do your research and always plan for a liberal amount of time; some applications are extremely detailed. Always be truthful on your visa applications— always. We have had good luck with Passport Visas Express (no affiliation) , but there are many reputable options.

Getting Organized

We have found that a divided file folder is the best way to organize information, copies and country-specific documents. I also have a separate file folder with the originals, which I keep hidden but accessible in the vehicle. My original passport always stays on my person and never in an easily accessible pocket. Several expedition-grade clothing companies design hidden pockets into their clothing. For example, Triple Aught Design’s pants have a second, floating, rear pocket that is only accessible from inside the waistband. I keep a wallet in my front pocket with only enough cash for the day (usually about $100 USD) and my driver’s license. Inside my shirt, around my neck, I keep a passport holder with additional cash (about $500 USD) and copies of my driver’s license, vehicle title, vehicle registration and passport, and an original of my international driver’s license. I also keep a flash drive with copies of all documents and a backup of my best photos from the trip… just in case. Have additional digital copies of the documents on your phone and in the cloud, all accessible. One other hack is to always hand an officer an international driving license, which you can keep several original copies of.

The Vehicle

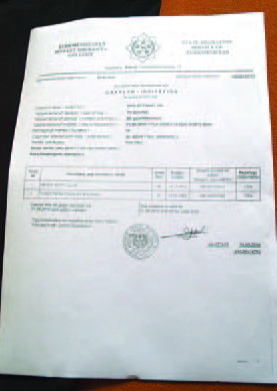

The more developed the country, the more they are concerned with people entering illegally. The less developed the country, the more concerned they are with a vehicle entering legally and not being sold. As a result, developing countries will take exceptional care in making sure the vehicle you are driving is not sold on the black market. To control this, requirements for entering with a vehicle fall under a wide range of vehicle importation systems. Some systems are brilliantly simple; using a stamp in your passport along with a written description of the vehicle; typically the VIN, license plate, make, model and color. You will not be able to leave the country until customs confirms that the vehicle exiting with you is the one you brought in, and they have cleared your stamp; most often with another stamp on top of the first one.

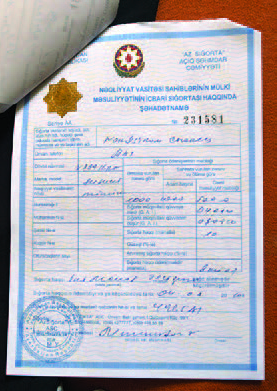

Some countries are particularly detailed and will record all manner of information on the vehicle and inspect the car with equal care. If you have nothing to hide, any issue is almost always resolved with patience and time. In most countries, the document they are most interested in is the original title; which should include a matching VIN, vehicle description, and some validation of you as the owner. This gets more complex if your company or someone else owns the vehicle. If this is the case, you will usually be required to provide a letter of authorization on the owner’s official letterhead, with the requisite signatures and the stamp of a notary. Ensure that the letter is executed during the same calendar year in which you are traveling (this applies in Panama and Mexico, in particular). I have even experienced a engine number inspection, so don’t make those up- know what the numbers are.

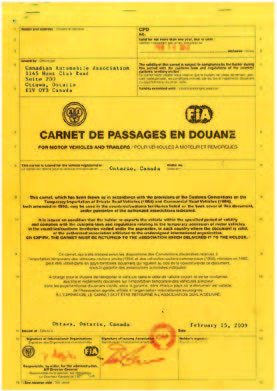

The Carnet de Passage

The Carnet de Passage (Carnet) is a temporary importation document that financially bonds the vehicle while in the host country. A significant number of countries still require a Carnet. Fortunately, that number is decreasing. As an odd development, Australia now requires it (as of 2009), unusual for a developed country, especially one without a land border. The Carnet is particularly relevant for travels in Africa, where its use is still the most common import method in many countries. A Carnet is obtained through an automobile association on your continent and financially secured with a cash bond, letter of credit from your bank or an insurance policy. The insurance policy is most common, although the most expensive choice. Depending on the country, you may be required to post a bond for up to 300 percent of the value of the base vehicle. Consider that before bringing your Unicat to Mongolia.

The Equipment

Having your equipment organized and well-documented will greatly facilitate smooth border crossings. Have a list (with copies) of all electronics in the truck, including cameras, radios, computers, etc. In my experience, we have never been hassled for having one camera and one computer per vehicle occupant. At some borders you will be required to complete a declarations document with a description of the equipment and its value. It is not uncommon for the border custom official to inspect your vehicle to verify that the declaration document is accurate. Full disclosure is important, but it can be useful to be somewhat cryptic in the description, for example with satellite phones or BGAN units. Listing a “Motorola 9555 Phone,” rather than a satellite phone might simplify the inspection while still being honest.

It is critical to know the laws of the country you are visiting, as some countries require permits and permission before bringing any radio frequency devices in; especially satellite communication. Russia in particular is serious about satellite communication permits, but no website indicates the means of obtaining a permit. The same is true in India. Even an inReach may cause issues, so always declare.

At the Border

Depending on the border you nose your vehicle up to, you may find order and efficiency, or utter mayhem. However, the process is almost always the same; so park the vehicle within sight of the customs and immigration buildings, grab your file folder and lock the car. I recommend that you keep your camera out of view. In most developing countries you will be mobbed by moneychangers and offers of assistance. In most cases, exchanging currency is fine. However, you should know the exchange rate in advance (there are great iPhone and android apps for this), and it is usually easier to do with smaller denominations. The offers of assistance can be quite valuable and allow for some efficiency if you feel the person is trustworthy. As a rule, never give them any paperwork, but use their services to get from building to building. Negotiate the fee up front. (Editor’s note: Experience has led me to never trust anyone who says, “Ah, my friend… trust me my friend.”)

The most important consideration at the border is to be patient and courteous. You are visiting their country and the border officials are just attempting to do their job. Respect and a smile will do wonders. In all of my travels, the most hospitality and kindness we encountered was at the Tajikistan/Uzbekistan border, where the officials welcomed us warmly to their country, smiled and helped us navigate the process. The least hospitable you may ask? Entering back into my own country—America.

The Border Dance

This is what you can expect at a typical border; however, there are a few things that are unique to specific regions of the world. Of course, every border is a little different, and this list cannot be all-inclusive. The items in bold are typical.

Immigration

1. Approach border post: Have vehicle organized and all documents available. Avoid cash or electronics in plain view.

2. Immigration: Have passport and secondary means of identification available. Passengers may be separated from each other.

3. Visa confirmation

4. Documentation of entry: Visa stamp and/or passport stamp.

5. Health and shot record review.

6. Immigration payment: This varies by country and can be as high as $130 USD. Most borders have nominal (or no) fees.

7. Detailed itinerary: Some countries require a detailed route and intended lodging disclosure. Some countries require tourist registration to be recorded each night on a tourist card.

8. Interview: Some countries require an extensive interview at the border post, which may include questions of military service, drug use, purpose of visit, etc.

9. Government Minder: Limited countries require a minder to accompany the visitor throughout their travels.

Customs

1. Vehicle importation: Vehicle importation is typically recorded in the passport, although many countries are switching to electronic records. Vehicle importation may also be regulated via a Carnet de Passage. Documentation may be simple or extremely complex, including engine serial numbers and a thorough inspection.

2. Customs declaration: The declaration records all items of notable value, as well as currency.

3. Simple vehicle inspection: Limited inspection and most items remain in vehicle.

4. Detailed vehicle inspection: Everything removed from vehicle; common when entering Russia.

5. Non-native species inspection: Vehicle inspected for cleanliness, dirt, seeds and insects. Border officials may spray the vehicle or require thorough cleaning.

6. Food inspection: It is common for vegetables and fruits to be confiscated at borders. Meat can also be limited.

7. Drugs and alcohol: Some countries may require all medications to be declared and their use disclosed. Many countries do not allow alcohol to be imported, or limit the volume allowed.

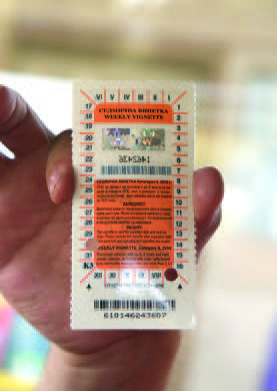

8. Payment of road tax: A road tax is becoming more common. It can be a flat fee, based on engine displacement, or the estimated mileage you will drive.

Avoiding Trouble

While the aforementioned planning is essential to safe and efficient transition between countries, reality often dictates otherwise. Borders may be closed, roads can be washed out, paperwork might get lost, or maybe the officials just decided they do not like Triumph motorcycles. This is where the border adventure begins; it will test your adaptability, patience and attitude. Remember, honesty, patience and a smile resolves most issues. I have heard far too many travelers brag of hiding food, lying about documentation and paying bribes. This will just breed trouble for you or for those who come later. I have made some dire mistakes, including intentionally and unintentionally crossing borders illegally. All have resulted in significant headaches and even militias with raised rifles and threats upon threats. Remaining calm and smiling always helps in the long run.

When I say most issues I mean this in the literal sense. There will be times that nothing will resolve a problem; you will need to stay in no-man’s land until another official arrives, documents can be delivered or a border has been cleared. We encountered this entering Kyrgyzstan. The border was closed due to ethnic fighting in the region and they would not allow passage, or even talk with us. Eventually, a French woman arrived who knew the residing officials; she negotiated entry on our behalf. Remember to be patient—you are on their schedule.

The Bribe

Unfortunately, much of the world is still lubricated with a greased palm. As a result, you may pay a bribe unwittingly or you may make the choice to do so consciously. While it is important to note that every situation cannot be controlled and exceptions are justifiable where personal safety is at risk, it is our opinion that bribes should (generally) not be paid. The reason for this is both ethical and practical. If you pay off a border official because your documentation is incomplete, it could compound the problem during a routine traffic stop or upon exiting the country. If you expedite your entry with a few dollars slipped into a handshake, it sets a precedent, or expectation for those who follow. Every traveler must set their own standards, but please consider those that come after you. (Editor’s Note: We discuss bribes in detail in our article The Truth About Bribery)

Border crossings are a necessary component of international overland travel and can be viewed as either a hassle, or as a rewarding and interesting part of the journey.