Photography by Graeme Bell, Luisa Bell, Keelan Bell.

Designed to enable access to specific and relevant information, travel apps have become an integral part of the modern overland experience. But, is this an entirely positive development? Are these apps essential? And how have these apps changed the overland travel experience?

It is 2010 and late in the day—a long, dusty, difficult day in a distant land. The family is tired, the Landy is running low on fuel, and we need to find somewhere safe to camp for the evening. Showers and clean toilets would be awesome, a fire pit would be excellent, and an electrical connection would please everyone, but these are mere luxuries. What we need most is security. We have encountered this situation countless times across five continents and have in the past always managed to find a safe haven, be it a gas station, a parking lot, a quiet spot up in the hills, or an actual campsite. And we have almost always had an adventure while searching for these havens where the night and those who populate the darkness have left us in peace. It is, in part, the insecurity of remote, long-distance travel which adds the spice of adventure. Leaving a haven each morning, not knowing where you will lay your head that night, is both daunting and exhilarating as you explore further into the unknown. This is how long-distance overland travel has been for centuries, the daily experience of the brave explorers who have sought a unique experience. By throwing yourself at the mercy of the road, of the communities which you encounter, you grow as a person, find strength which you never knew you possessed, make friends, and immerse yourself into cultures unhindered by a reaction to those who came before you.

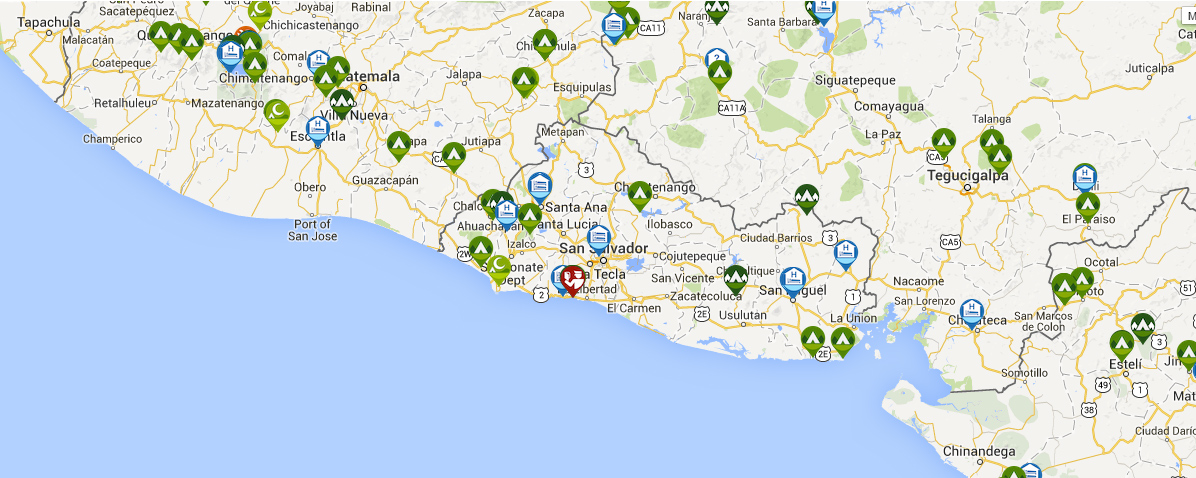

Overland travel has changed fundamentally, thanks to the march of progress. I will be the first to admit that there have been times when apps like iOverlander, Wikiloc, WhatsApp, and others have been incredibly useful. Our most recent journey across West Africa (2019) would have been so much more challenging had we not had the ability to switch on a smartphone and know that at the end of a 300-mile trek across northwest Nigeria, we would have three reviewed options for overnight accommodation as well as the location of fuel stops and budget restaurants where we might purchase a meal and a place to overnight. This information was even more important and reassuring when we had members of the family suffering from malaria and other illnesses and a budget under constant assault. I was grateful for those apps when I had no energy, the sun had set, and the innocence of daylight had slipped away. But…the journey and the adventure itself was altered. We allowed ourselves to become lazy explorers, lazy in that where before we would pore over maps and study the route, make connections with travelers heading the other way, immerse ourselves in the geography of the country, and engage the local communities, we no longer needed that level of preparation and involvement. We discovered too late that we had become connect-the-dots iOverlanders, following a well-beaten path, living someone else’s journey.

There are (in addition to the many positives) downsides to these apps for remote communities, too. Example. Recently, a generous motel owner in a small, tidy Congolese town had welcomed an overland traveler and had offered him free parking for a few nights, invited the man and his wife to share a meal, and allowed them to use the ablutions at no cost. The overlander posted a glowing review of the motel on iOverlander, and now that generous motel owner no longer leaves his chair when he sees yet another expensive foreign overland rig roll into his compound with smiling penny pinchers behind the wheel looking forward to a free night or two or even a week.

To make matters worse, the occasional abuse of a host’s generosity is exacerbated by that generosity being broadcast to every overlander with an internet connection. There are some overlanders who have been known to take way more than they give, who are happy to squat and absorb the WiFi, use the facilities, and accept the host’s generosity and overstay their welcome.

Some businesses now cater to overlanders as they have found that these people are magically attracted to their doors. Prices are raised as proprietors seek to cash in on their newfound popularity. This creates dissatisfaction as travelers may have a false impression created by previous reviews, and business owners resent “wealthy” foreigners with short arms and deep pockets on the hunt for a bargain.

Crime is another unforeseen problem associated with travel apps as opportunists take note of areas that are popular as free and wild campsites and other insecure overnight areas. A German traveler was recently attacked and bound while his vehicle was stripped of all valuables at a popular and well-documented free camping spot in Angola. This is apparently occurring with more frequency globally. There are communities that are no longer welcoming to overland travelers who seek to free camp on their land as they attract opportunists and law enforcement, causing problems for the community.

Additionally and unfortunately, not all overlanders are conscientious, and there have been recurring problems of improper waste disposal, the building of fires in sensitive areas, litter, substance abuse, and general disrespect. It is worth noting that these popular apps are available to everyone, and there is no way to control who has access to site and resource information.

As with everything in life, there are pros and cons, and travel apps are no exception. When we circumnavigated South America, we did so without any apps other than unreliable navigation apps. Heck, we didn’t even have a GPS. And what an adventure it was! Each day was unique; we found our way the old way, and we engaged fully with the communities encountered. We set aside a couple of hours every afternoon on the road to finding an overnight spot, hardly ever stayed in hotels, hostels, or motels, and though we did have some tough times, we had the time of our lives. Travel apps have taken much of the risk (and therefore much of the reward) out of overland travel. There is a multitude of apps providing up-to-date information and connection regarding accommodation, weather, language, currency exchanges, restaurants, messaging, mapping, wine, beer, and document storage. Overlanders are connected like never before, and traditional overland routes are now saturated with some who have not earned the experience to take on these adventures safely. Ask yourself, can you, with your knowledge and skills, travel confidently without the use of apps?

I suppose it is a personal choice.

Going forward (we will soon depart for a Cape Town to Vladivostok journey), I am committed to using travel apps as a last resort or even an emergency resource. I crave a novel experience, for each day to be unique, to travel like those overlanders who went before us and blazed a trail. I do not want to simply commute and follow the herd. Now, if only I could convince the family.