This article was originally published in Overland Journal’s Gear 2020 issue.

Northwestern Zambia is covered in soggy floodplains and even soggier drainage wetlands, sandwiched between endless acres of strangling forest. Deep below the surface, however, are rich deposits of copper ore which have long been attracting teams of exploration geologists to this inhospitable land. They are sent in for months on end, armed with canned food, geological maps, and sample bags to fill with soil. The bags are then sent back to labs to test whether their geologists’ noses are indeed sniffing out the copper or not. But even with highly trained professionals and the latest technology, finding copper is no easy task when a thick blanket of younger sandy regolith covers most of the bedrock in which the ore lies. Projects are often abandoned to go off and search in a new area. But for these lucky explorers, paid adventure is had in wild places very few are fortunate enough to visit.

Getting in and out of these remote areas is left up to a doggedly reliable fleet of Land Cruiser 70-Series pickups, and mobilizing is well-planned and generally without incident. But on one occasion, a season in the field was nearly over before it began.

It was the tail end of a vicious rainy season in the mid- 1990s, and a group of exploration geologists had just switched off the idling diesel engines of their two pickups. Getting out onto the muddy ground, bewildered at the vast expanse of water shimmering before them in the mid-morning sun, they began to chatter in puzzled tones. By this time of year, the water should have subsided to leave a muddy track across the floodplain, which they had navigated successfully in years gone by. Instead, there was an endless swamp as far as the eye could see, which no mortal vehicle could navigate—unless it could float, too.

A flask of coffee was produced from behind the seat. Leaning over the 1:250 000 Senanga map on the hood of one of the vehicles, the problem was discussed. Their only option seemed to be to drive the 20 hours around the swamped floodplain into the prospect area. But one of the crew, who spoke some of the local Lozi language, had chatted to a group of locals in the trading store in Senanga the day before. There was apparently an Angolan refugee village on the opposite side of the floodplain; the Zambian army was using what the locals called mukolo wa kwenas or crocodile boats to transport supplies. With half the geologists being seasoned veterans with stiff joints, and the other half possessing the curiosity of youth, the 20-hour drive on the bumpy road around the floodplain was voted as plan B. The Cruisers made an abrupt U-turn back to Senanga to see if they could pay their way onto one of these amphibious vehicles.

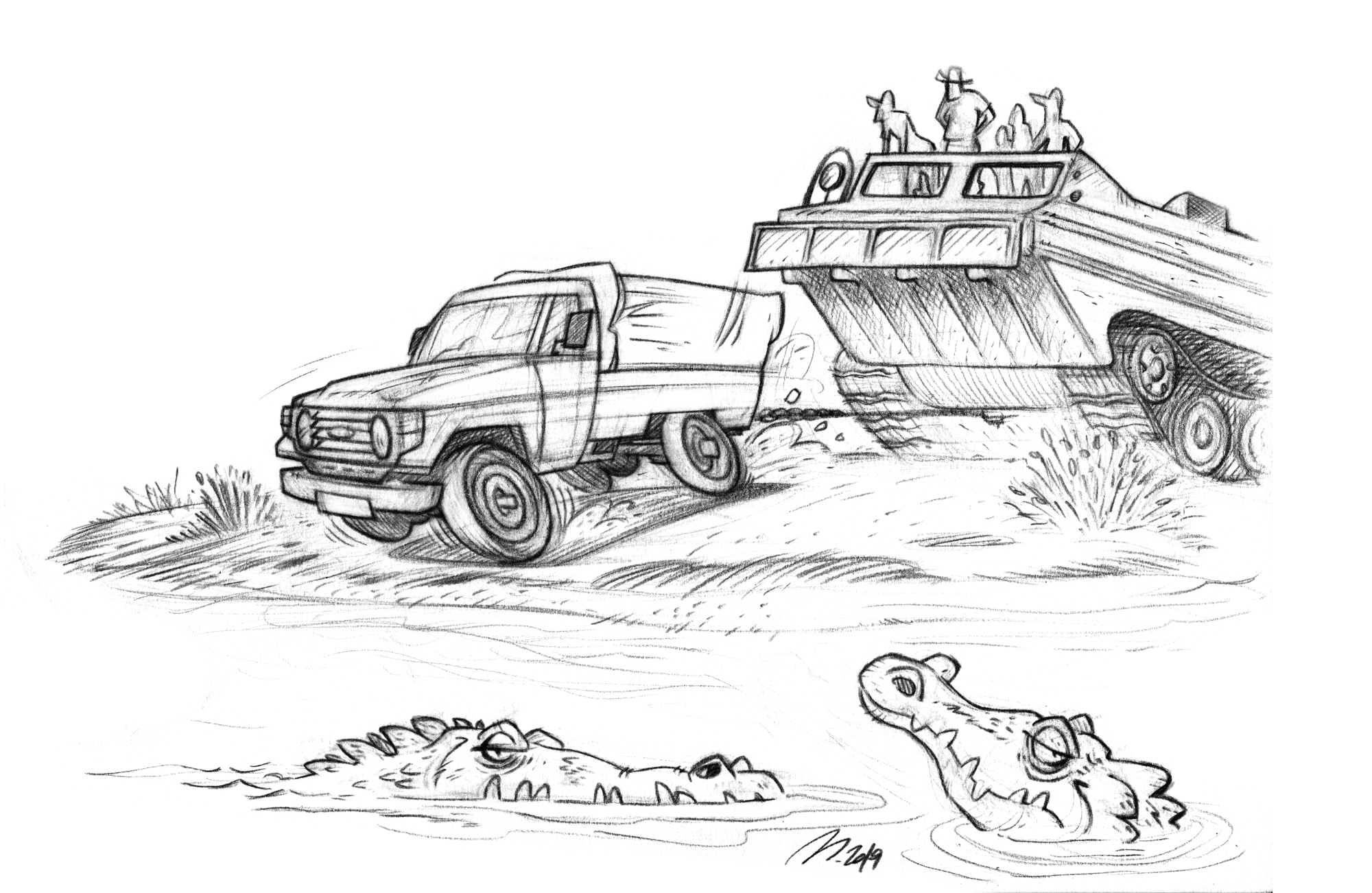

Almost immediately they came across a convoy of bicycles being pushed, not ridden, down the road with all manner of sacks, boxes, and caged chickens strapped to them, evidently heading directly for the water’s edge. The Cruisers swung their noses onto the same track, and it wasn’t long before in front of them lay indeed what looked like a pair of gigantic crocodiles being loaded with cargo. They turned out to be tracked amphibious cargo carriers of the Sovietmade PTS type. They were not much more than a long hollowed-out tank with tracks, but no turret or gun—just a huge walled deck and loading ramp. Loading had just begun, and so it was negotiated with the military captain in charge that for a 44-gallon drum of diesel and a carton of Marlboro cigarettes from Johannesburg, the two Cruisers and four geologists could squeeze on with everyone else. Diesel was in short supply in these regions, and though none of the team smoked, boxes of cigarettes were indeed a useful currency in the region too.

The loading tracks onto the tanks were made for much wider military trucks, so driving the Cruisers on was a hairy business from the start—perhaps an omen for the trip ahead. After much stopping, reversing, and nail biting, each amphibian was loaded with one Cruiser nestled into the middle of the deck surrounded by 15 people and 2 tons of maize meal. The ramps were raised, and the vehicles lurched into the water, diesel turbines whining, the tracks leaving a muddy wake behind them.

The floodplain to be crossed was only on one side of the Zambezi River. But heading south in the same direction as the river’s flow, it made sense that the vehicles make use of the current and drift down the river to exit farther down. The weight of the Cruisers, people, and maize meal caused further nail-biting and prayers when the great green rolling waters of the famed Zambezi River were spotted ahead. Neither driver made any attempt to slow down. The carriers plunged nonchalantly into it at full speed with nothing but a bob. Power take-off was switched from tracks to propellers, and off they went, the drivers not batting an eyelid nor missing a drag on their cigarettes.

A group of passengers had been getting stuck into a pot of local beer, and when it was time to relieve themselves, the drivers obliged. They pulled up on a raised sandy island near the bank of the river, forcing a pair of real basking crocodiles to slink grumpily back into the water. With all of 30 meters to fit on, the second carrier squeezed up behind the first one, whereupon it immediately stalled. Its driver, the captain with whom the ferry deal had been struck, cursed in tones that made it obvious something was seriously wrong. Batteries, it seemed, were of low importance here, and were never properly maintained. The men quickly brought the other amphibian up to pull-start it, and in so doing, stalled that one too. Thirty people, four vehicles, and 4 tons of maize meal were now marooned in the middle of the crocodile-infested Zambezi River, miles from any help.

Not to be undone, the geologists and soldiers wired up four Cruiser batteries into a series to produce 48 volts to start one of the amphibians. This had no effect on the diesel turbines and was draining the batteries too quickly. The only option left was to try and pull-start one of the amphibians with a Cruiser (remember, these vehicles did not have wheels but tracks).

Everybody got to work offloading the front amphibian, a Cruiser was hitched up with a chain, and every single person lined up along the side to push. In first gear low range, the six cylinders and 130 horses in the Toyota 1HZ engine inched the pickup forward, tires slipping but slowly gaining traction. With 20 meters of runway to work with, there was little room for failure. The Cruiser was nearing the end of the island, about to plunge into the water itself, when the crocodile boat roared into life.

With both carriers running, the Cruisers again crawled up the loading tracks. They were walled off with sacks of maize meal, atop of which the passengers chattered in high spirits at the action they had all been part of, passing around more pots of beer. Off they went, plunging back into the waters and out onto dry land sometime later without further incident. The geologists spent a productive couple of months sampling soil on the other side and set off for the long road home, the weight of canned food replaced with meticulously labeled bags of sifted soil. The floodplain had by now dried up, and finding their planned track, they crossed the whole thing in less than a couple of hours.

In the years to come, the copper in that prospect across the floodplain proved to be insufficient, and the work was subsequently abandoned. But whenever traveling through Senanga to other prospects in the area, the geologists stopped by the military office bearing gifts from Johannesburg. Everyone would share a laugh over the time they had all very nearly been marooned on a desert island in the Zambezi River.