“Okay, the big question is how to approach this point. From the north? The south?”

Coen was zooming in on his iPhone, enlarging the area mentioned in the Lonely Planet guidebook. It’s the first guidebook we’ve ever had that includes a list of GPS Waypoints for certain sites. For overlanders, who typically travel without a guide, this is just perfect in a country like Mongolia, which is vast and empty but has many places of interest in the middle of nowhere.

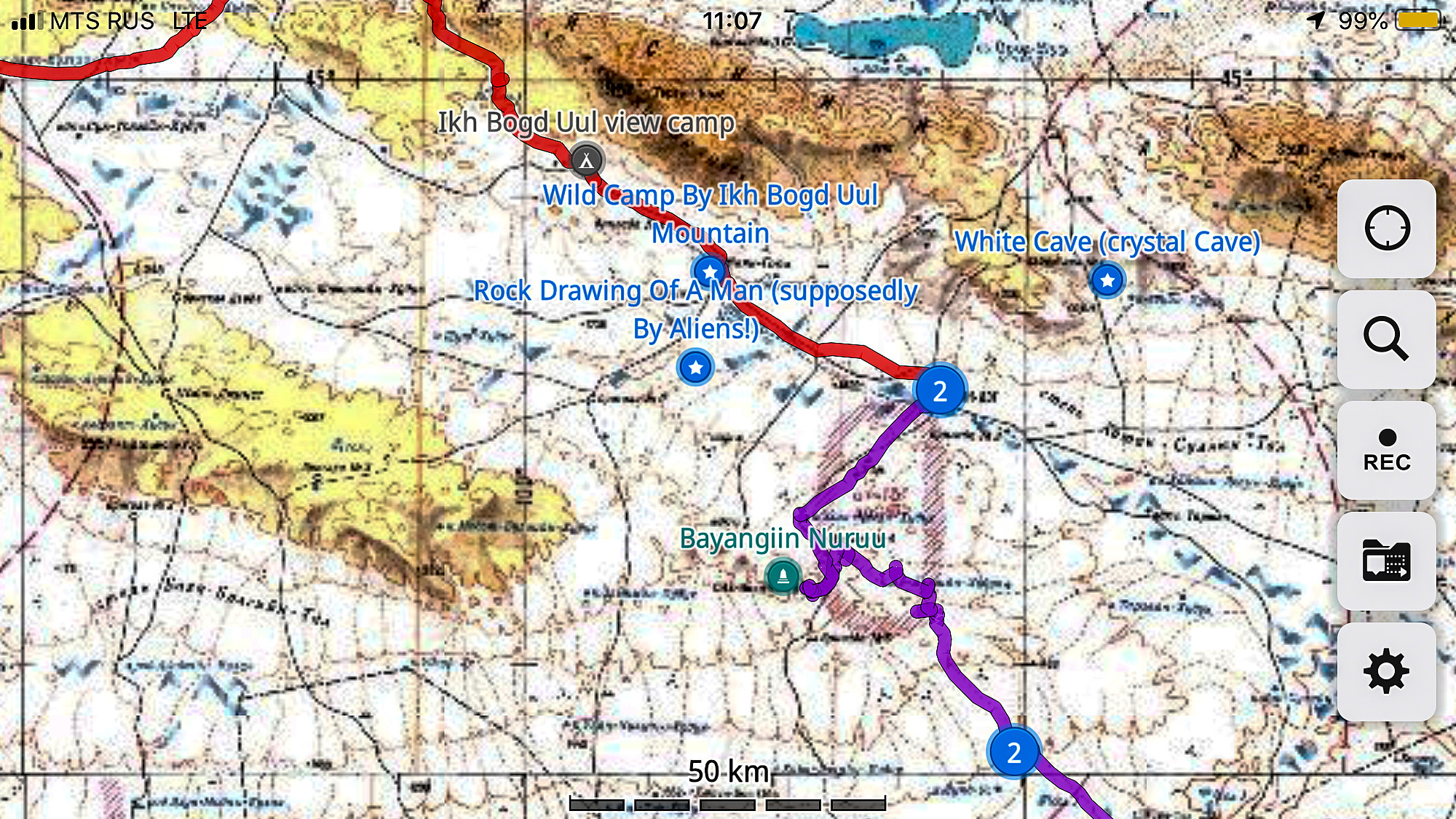

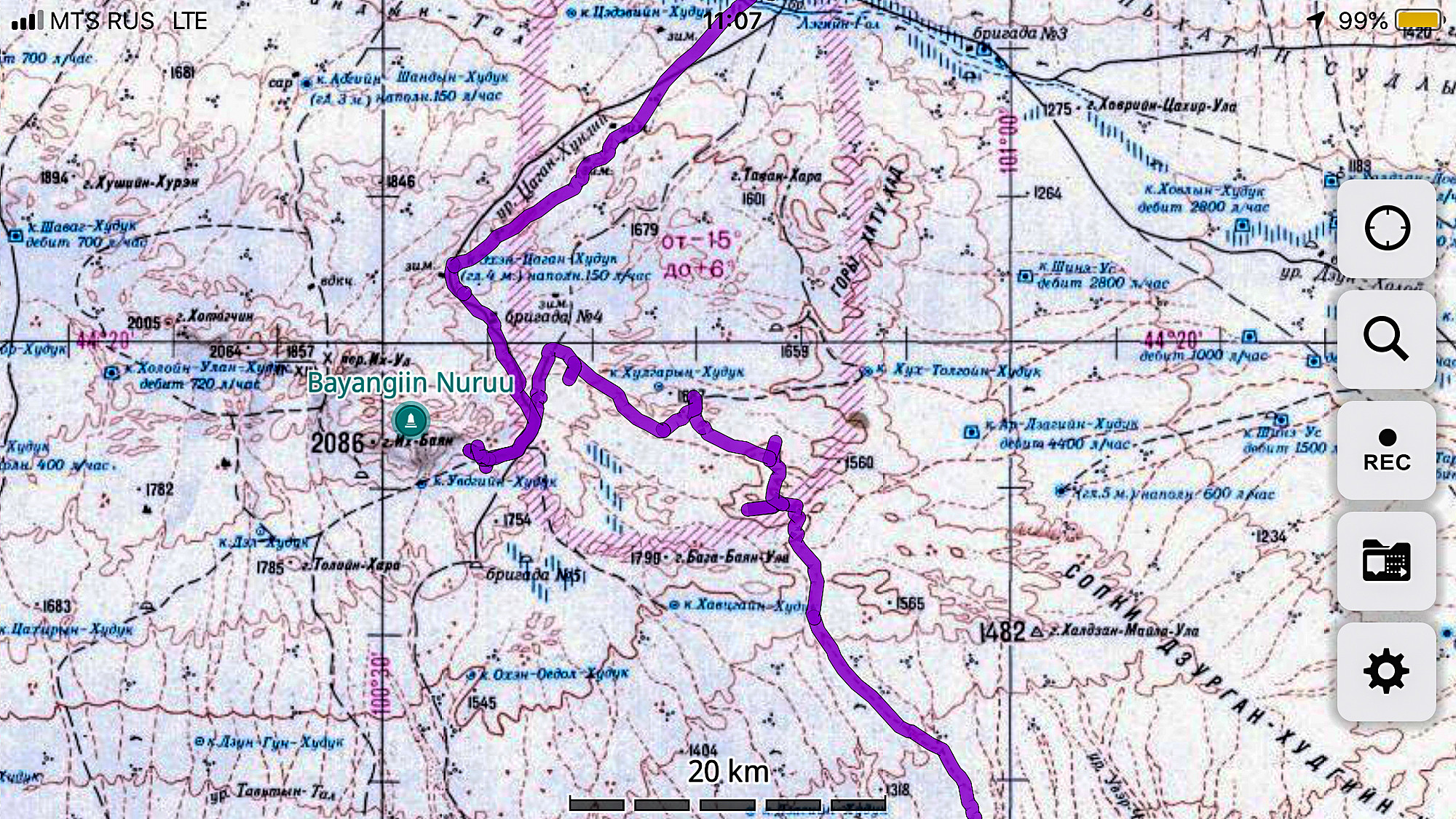

Besides a waypoint in a mountainous area the guidebook gave no other description than, “A canyon filled with well-preserved rock engravings and petroglyphs depicting hunting and agricultural scenes and dating back to 3000 BC.” We should have searched for details when we had WiFi, but we hadn’t and so depended on maps. The roads on our Reise KnowHow paper map were not consistent with the trails on Open Street Maps nor our digital Russian military maps, but after a couple of weeks of traveling in Mongolia we had grown used to that. Unpaved roads tend to change over the years as weather destroys them and drivers create new tracks.

“Well, let’s give it a try. We’re coming from the southeast, so let’s see if we can get there from this direction.”

We were camped in the Gobi Desert in southern Mongolia, a region we had explored for the past two weeks or so. The Gobi extends for 3,000 miles along Mongolia’s southern border and runs deep into China. This ancient land has been inhabited for thousands of years and large collections of petroglyphs (imagery gouged or chipped into the surface of rocks or boulders) are reminders of those days. While the Gobi does have sections with Sahara-type dunes, the area we were driving in was a treeless desert of graveled plains with sparse vegetation that alternated with rugged parts with barren, rocky outcrops. The region is inhabited by nomads who, like in the greener north, keep goats and sheep. They use fewer horses than their northern neighbors (the herders mostly move around on 150cc Chinese motorcycles) but have lots of camels.

At intervals there are villages or towns where nomads have settled down even though many still live in gers (the Mongolian term for yurts). Contrary to the gers in the countryside, in towns they are surrounded by wooden fences so people have space to park their car/motorcycle and store belongings. The towns generally are uninspiring and we stopped just to stock up on fuel (they all have a gas station), food and water. Pretty much every town has a playground for kids with colorfully painted wooden fences as well as a white painted hut to protect a well where people go to get their water in buckets or jerrycans (and where we could fill our water tank). The food stores are small and their stock consists for eighty percent of sugary foods and drinks. The rest is mostly frozen meat, some food in cans, and a limited quantity of vegetables and fruits. Except for the main thoroughfares from Ulaanbaatar to the Chinese border, no road in this region is sealed.

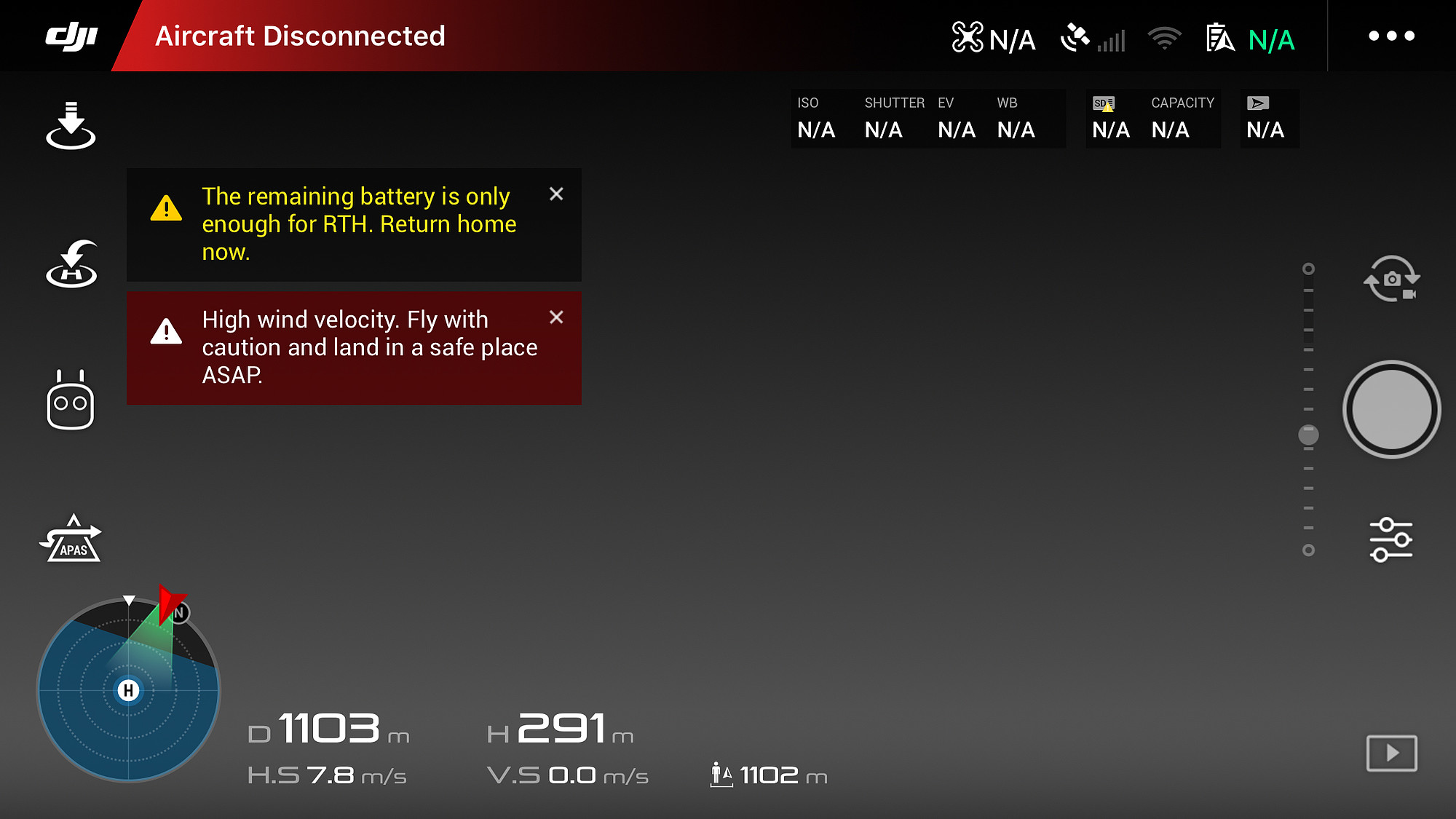

The day before we had struggled to get to any track that was on one of our maps, however, to no avail. It had been a long day of zigzagging through scrub, in some parts with thick and sharp spines until we’d hit a trail that we’d follow until it deviated too much from the direction we were heading in and we’d try another shortcut. To get out of this scrubby emptiness we decided to fly the drone and use it as a scout. At least this time there was no wind. Two days earlier when we tried the same tactic, the wind had become fierce and gusty the moment the drone was high and far away. A short message on the screen was enough to cause instant panic. “Contact lost,” it said. With me driving and Coen trying to figure out where to go we searched for a good fifteen minutes before we found the drone back, fortunately undamaged.

“Okay, if we go north from here, and then northwest, we should get back on a road,” Coen concluded from the drone’s observations. From the air it looked simple enough. On the ground, it was a different matter. We followed tracks that inevitably led too much to the east. We turned around and rumbled across other tracks cutting through gray-brownish plains. Be patient in the Gobi Desert! It is immense, the distances often deceptive and when the sun is burning with a fierce, searing heat you wonder whether it’s water in the distance or yet another fata morgana.

It’s exactly this unfathomable greatness that at times gave me a sense of claustrophobia. Would we ever get out of here again?

All of a sudden we were driving through a landscape covered in rocks and, just as unexpectedly, the ground was flat again. We found the main trail and barreled across the corrugations, the vibrations tearing us and the Land Cruiser apart. After a couple of hours, passing only two gers but no people there to ask for directions, and a couple of grazing camels and herds of goats we reached a dark-red canyon.

Our waypoint was promisingly pinpointed in that canyon.

We entered the gorge. The Land Cruiser rocked from left to right over the big, uneven boulders and after a few curves we hit a steep, natural wall – in wet season probably a minor waterfall. The Land Cruiser could go no further. Coen turned the ignition key and we stood in a silent world. We discussed turning around or going for a walk. Food often brings solutions and so I decided to prepare some lunch first. While I was doing that, I heard Coen shouting, “I see petroglyphs!”

Really? Here?! By a sheer stroke of luck, while I was preparing peanut-butter sandwiches, Coen had climbed up the rock wall to take a photo of the Land Cruiser and spotted stone-age rock carvings.

What a marvel! We felt the luckiest people in the world.

Rock faces with animals, hunting scenes, people on horses with bows and arrows. We called each other over from one rock to another, each time elated to find yet another light-colored scene depicted on the dark rock surface. Look, a deer! A mountain goat!… It was fantastic.

The question lingered. How had that waypoint been established? Was it just a general point for this canyon? Or was it connected to a specific point? We set out for a walk through the dry riverbed, thinking the specific waypoint itself was a mere four kilometers walk. However, the canyon constantly looped back on itself. Our water ran out as we stood atop a hill in an attempt to shortcut some of the loops, looking out over the vast expanse of wilderness.

The sun burned fiercely and everything looked the same – the main canyon, its forks. I wasn’t even sure how to get back to the Land Cruiser. But leave that to Coen – fortunately he had marked the vehicle on his phone. With more paintings on either side of the canyon during our hike (but nowhere as many as near the Land Cruiser) we felt the GPS marking probably was for this canyon in general. Totally satisfied with the treasures we had spotted, we returned to the Land Cruiser and set off for our next adventure in the Gobi Desert.

(Afterthought: On our return to Ulaanbaatar, we learned from other overlanders that we were wrong. The GPS waypoint does indicate a specific spot. And it is mind-blowingly beautiful. Loes and Harm (Sixwheelseast.com) shared a photo and yes, of course, there was this sting of jealousy for a moment. But oh well, that’s what life is. You make decisions, make choices, and sometimes you could have done better. For those who want to go:

The Rock paintings of Bayangiin Nuruu (nuruu means canyon),

GPS: 44.286967, 100.522150