Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal, Spring 2019.

When following back roads across almost any state in the American West, you’ll encounter a patchwork of public and private lands. “No trespassing” signs often adorn fence lines surrounding the latter, while more welcoming ones often announce your arrival onto federal public lands. These might read “Welcome to Sawtooth National Forest: Land of Many Uses” or “Now entering Your Public Lands, managed by the Arizona Strip Field Office.” The country’s federal public lands are managed for a broad array of uses including grazing, timber harvesting, mineral extraction, recreation, wildlife habitat, and wilderness conservation. And these lands are important in diverse ways to local residents, Native American groups, the public at large, corporate interests, states’ economies, and the federal government.

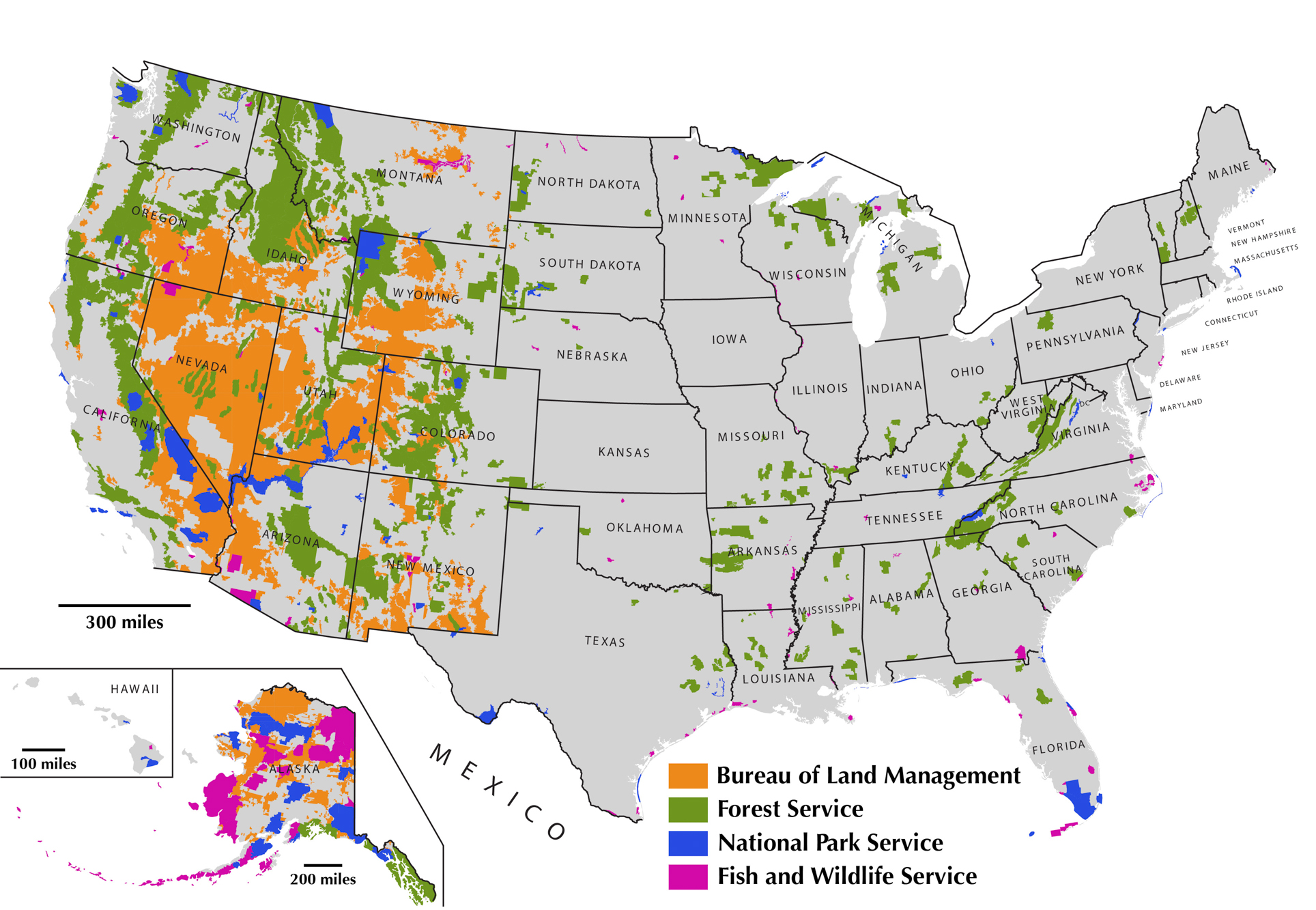

Public federal lands in the United States constitute approximately 25 percent of the country’s land area, have a dizzying list of special designations and acronyms, and are administered by several agencies. Most of this portion is managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), 10 percent, US Forest Service (USFS), 8 percent, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), 4 percent, and the National Park Service (NPS), 3 percent. The greater part of these holdings are located in the contiguous states west of the Mississippi River and in Alaska. Many individual states also have considerable land assets, but some state-owned lands are not considered public domain as they are generally managed to generate revenue through leasing and outright sale.

Our focus will be on the origins of the two most extensive types of public lands: national forests, and lesser-known BLM lands. National forests, totaling 193 million acres, were mostly established in a period of just 16 years spanning the turn of the last century. BLM lands, spanning 248 million acres, were not formally cemented as public lands until 1976. However, the history of how these millions of acres were set aside with the national interest in mind began more than two centuries ago when the federal government began selling and giving away its rapidly growing territory.

PUBLIC DOMAIN LANDS

The lands that so many of us cherish today as our federal public lands (as well as all other areas in the United States) were once the territories of hundreds of indigenous groups. Through relocation, forced assimilation, treaties, and genocide, lands were taken from these people. Today, indigenous groups continue fighting to regain some of their ancestral lands—for the recognition and protection of sacred places, water rights, resources promised in treaties and court orders, sovereignty, and for so much more.

The carving up of America’s land holdings began shortly after the nation’s inception, and thousands of Congressional acts and statutes in the subsequent 200-plus years dictated their fate. The gridded Public Land Survey System was initiated in 1785 to aid in the disposal of these as unreserved, unappropriated, or vacant “public domain” lands. As the fledgling United States expanded through subsequent territorial acquisitions, the acreage of public domain lands grew exponentially. With this growth, Congress initiated an era of doling out land grants—giving away public domain lands to private parties—to establish sovereignty over its new territories and promote economic growth through expansion, settlement, and industrialization.

The General Land Office (GLO) was instituted in 1812 to oversee the continued disposal of public domain lands, and during the 19th century, a full 50 percent of the land area of the country was given away. An eighth went to homesteaders, and another eighth went to railroad companies; agricultural, mining, and logging operations also received substantial grants. Newly formed states also received public domain lands, but large regions of unappropriated lands remained within each state. The enabling acts agreed to by each fledgling state upon entering the Union articulated that the state would have no claim to or title over the remaining public domain lands within the state’s boundaries. In exchange, states were granted two 1-square-mile sections within each 36-square-mile township across the state for schools. The 1841 Preemption Act also allowed new states 500,000 acres of public domain land, and the 1862 Morrill Act added additional acreage to aid in the founding of state colleges.

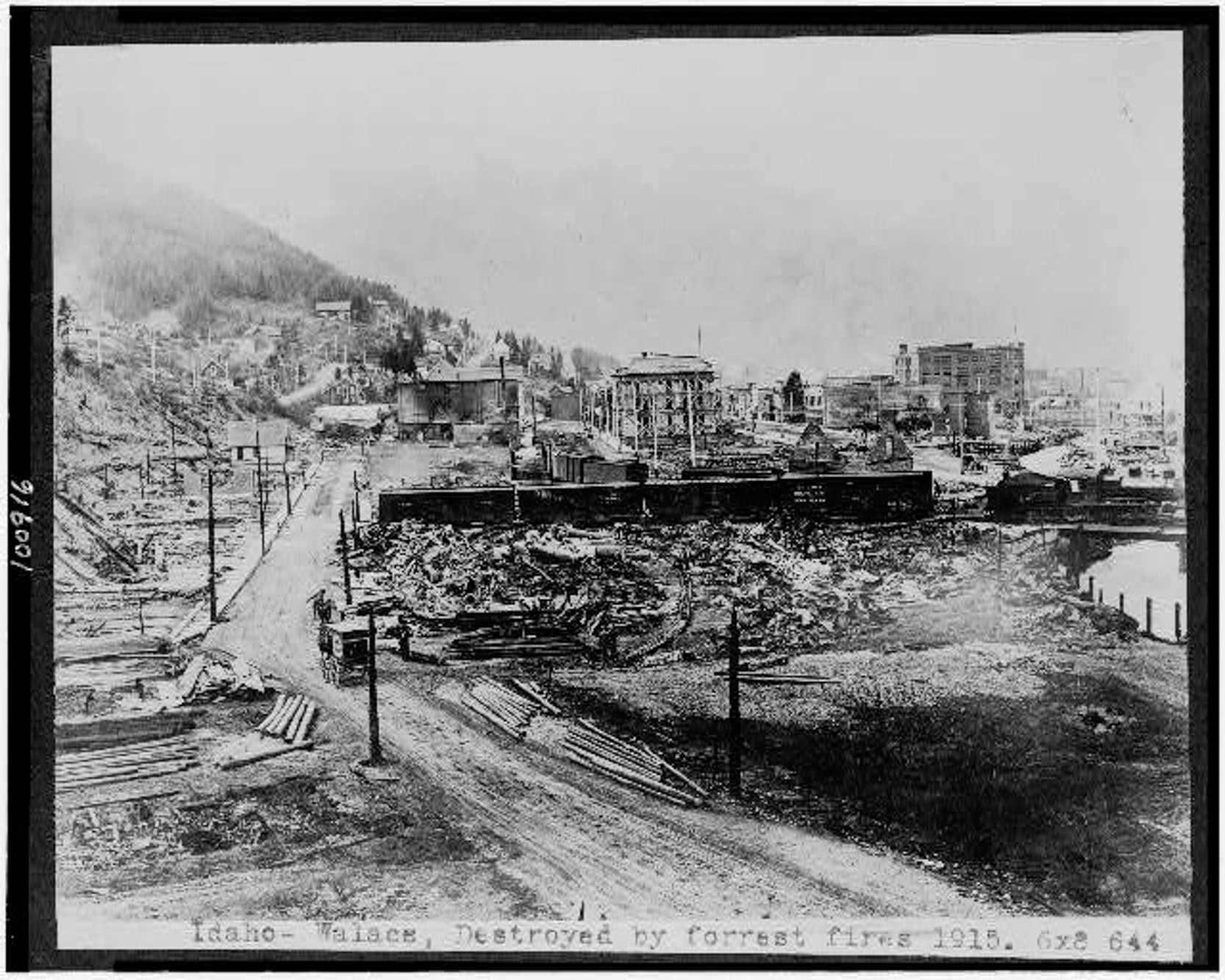

By the 1890s, most territories had become states, railroads crisscrossed the nation, easy-to-access mineral deposits had been claimed, readily arable lands were being farmed, and the enthusiasm of westward expansion began to subside. However, hundreds of millions of acres of unappropriated lands remained in the public domain, mostly west of the Mississippi. Use of these lands for grazing, timber harvesting, and mining by both residents and burgeoning corporate interests was minimally regulated. Extensive overgrazing, clearcutting of forests, illegal timber sales, and the fraudulent exploitation of mining and other land disposal laws became widespread. Irrigation surveys of the West led to concerns related to flooding and soil degradation resulting from the logging of forested headwaters. Large forest fires occurred regularly, and fears of a coming “timber famine” were fueled by the nearly complete harvesting of the once-great forests of the Great Lakes region.

An environmental movement grew in response, championed by influential sporting organizations and magazines such as the Boone and Crockett Club, Field and Stream, and American Angler, calling for the preservation of streams and forests. A new idea began to take hold: the concept that the federal government should preserve some of the public domain lands for the broader benefit of the public. Growing out of this movement were the first national monuments and the greater part of the national forests. The lands that have subsequently become managed by the BLM, however, remained in limbo and available for disposal until the 1970s.

CREATION OF THE NATIONAL FORESTS

The majority of the United States’ vast national forests were established following the 1891 Forest Reserve Act. In response to mounting concerns over the clearcutting of forests and the need to protect stream headwaters for irrigation and flood control, Congress passed a bill giving the president authority to set aside federal “forest reserves” from public domain lands, thus protecting them from disposal. In addition to also providing management of the country’s important timber inventory, then Interior Secretary Noble communicated that these forest reserves were to “preserve the fauna, fish, and flora of our country, and become resorts for the people seeking instruction and recreation” and preserve areas of “natural beauty, or remarkable features” and of “unique scientific interest.”

Within days of the act’s passage, President Harrison declared the first forest reserve around the periphery of Yellowstone National Park. GLO field agents labored to identify forested watersheds across the West suitable for this designation, and by the close of the century, dozens of reserves encompassing millions of acres had been set up. The reception to these actions was not entirely positive, however. After initially being closed to all public entry pending new use regulations, Congress responded to an uproar of discontent by opening the forest reserves to grazing, mining, and logging in 1897 under rules that were yet to be instituted.

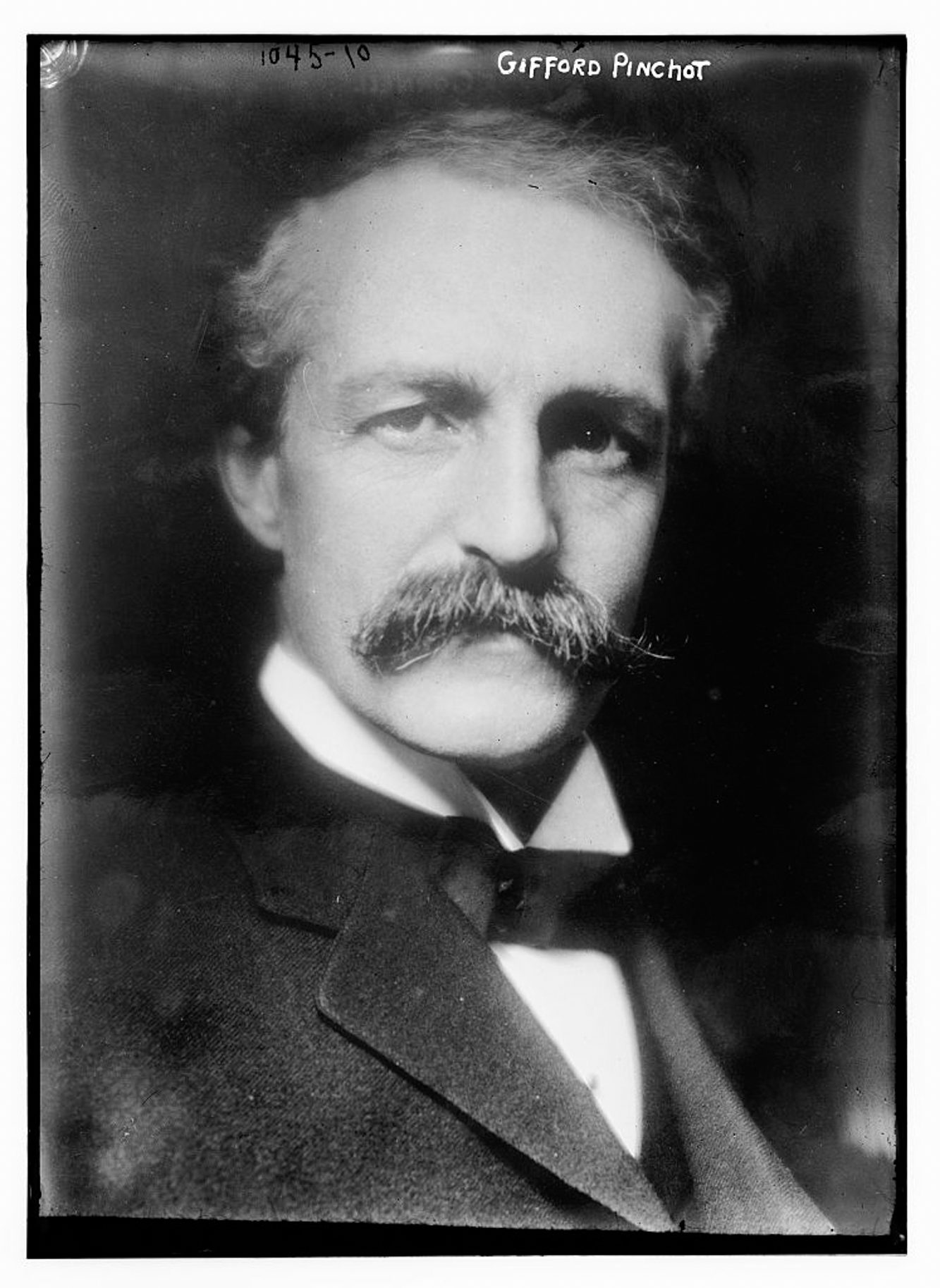

In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt named the charismatic conservationist Gifford Pinchot as head of the newly created US Forest Service. The mission statement of the agency stated “all land is to be devoted to its most productive use for the permanent good of the whole people, and not for the temporary benefit of individuals or companies…where conflicting interests must be reconciled the question will always be decided from the standpoint of the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run.” The forest reserves were then renamed national forests.

Pinchot lobbied Roosevelt to protect more of the forested West, and Roosevelt, an enthusiastic hunter and vocal conservationist himself, obliged. But Western states protested, and in response, Congress passed an amendment within an appropriations bill stripping the president of his authority to establish new national forests within six Western states. Roosevelt deemed it politically unwise to veto the legislation, so he asked Pinchot to direct his staff to promptly identify all remaining plots suitable for national forest designation. After proposed forest boundaries were outlined on detailed topographic maps of those six states, Roosevelt declared 16 million acres of new national forest immediately prior to signing the appropriations bill. This bill brought the short era of national forest creation in the West to a close.

The origins of the 25 million acres of national forests east of the Mississippi, from Minnesota to Alabama and Vermont to Florida, are starkly different. In most Eastern states, these forests are the only significant areas of federal public lands, the vast majority of which were purchased by the federal government from private sellers with the explicit approval of the states. These forests were brought into being to address both ecological and socio-economic concerns. Restoration of timber to clear-cut landscapes and abandoned farms, as well as protecting the watersheds of navigable streams, were the primary goals, and the USFS became the steward of a legacy of exploitive land use practices. During the Great Depression, federal funds also were directed to purchase lands in need of restoration across Texas and the South to help stimulate local economies and to create recreational opportunities for populations living in more distant urban settings.

Management goals for the national forests have evolved steadily over the last century. The initial focus on protection of forest resources transitioned to facilitating timber production beginning during World War I and continued well beyond World War II. In the 1950s, USFS support for outdoor recreation increased as the American public became more mobile and leisure-minded. Conservation of wilderness areas also became a priority. In 1960, Congress passed the Multiple Use–Sustained Yield Act, deeming the major uses of national forests to be of equal importance: outdoor recreation, grazing, sustained-yield timber production, watershed protection, and preserving fish and wildlife habitat. Mineral extraction, however, remained elevated above all other uses, and fighting wildfires continued to be a priority of the USFS.

THE LEFTOVERS

At the close of the 1920s, 235 million acres of unappropriated lands remained in the public domain, almost exclusively west of the Mississippi. Most of these predominantly unforested lands were overgrazed and brought no revenue to the federal government, but subsurface mineral deposits were of unknown value. Ultimately, these acres became BLM lands, but it was not until 1976 that it became clear that they would be permanently held by the federal government.

President Hoover, attempting to end the plight of disposing of the remaining public domain lands, recommended to Congress in 1929 that these lands be given to the states. Congress agreed, but not wanting to give up potentially lucrative mineral deposits, articulated that the federal government retain ownership of subsurface rights. Politicians from Western states responded with dismay, insulted at being offered millions of acres of abused lands. States rejected the offer and instead insisted that the federal government rehabilitate those lands and begin managing grazing.

Congress reacted by passing the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934, creating the US Grazing Service to manage the vast rangelands “pending final disposal” of the land. In 1946, the BLM was established by President Truman by merging the long-standing General Land Office and the US Grazing Service. The new agency was given control of 400 million acres of federal lands and nearly a billion acres of subsurface mineral rights, and primarily supported and managed the livestock and mining industries.

Multiple-use considerations and non-commodity land values like recreation, ecological characteristics, and scenic quality received recognition by the BLM in the 1960s and 1970s, and the fate of these millions of acres finally became clear—the public did not want these lands sold off. Following a mandate from Congress, the BLM had inventoried and classified its holdings to identify which were best suited for federal retention and which should be disposed of. Public input revealed that almost unanimously, individuals, ranchers, and timber and mining companies preferred federal ownership of the land. All parties believed they stood to gain more from public ownership than by being locked out by private possession.

The Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 codified that the federal government would permanently retain all remaining public domain lands managed by the BLM. The act also repealed nearly 2,000 older disposal policies and stated that “the public lands be managed in a manner that will protect the quality of scientific, scenic, historical, ecological, environmental, air and atmospheric, water resources, and archeological values…preserve and protect certain public lands in their natural conditions…provide food and habitat for fish and wildlife and domestic animals…[and] provide for outdoor recreation.” BLM lands have since been managed for multiple uses beyond the traditional commodity-based industries. A growing emphasis has been placed on recreation, and conservation has been prioritized, highlighted by the designation of millions of acres of BLM-managed National Landscape Conservation System properties and national monuments.

THE FATE OF STATE-OWNED LANDS

What has become of the millions of acres of lands given to states upon entering the Union? Often referred to as “trust lands,” these holdings have been administered with notable differences in each state. For example, Nevada rapidly sold off most of their holdings after being granted statehood. Others have held onto much more of their trust lands as a source of continuing revenue for schools and other public institutions through leasing parcels for agriculture, timber, and mining or through outright land sales. Some states also manage portions of their lands for recreation as another way to generate funds. But states are careful to note that the majority of these state-owned lands are not considered public, and it is not uncommon for public access to be restricted. Over the past century, support for transferring federal public lands to individual states has ebbed and flowed, particularly in the West, but the idea conflicts starkly with the intended purposes and goals of most states’ current land holdings.

THE FUTURE

For more than a century, expansive tracts of federal lands have been set aside for the benefit of the nation as a whole rather than the benefit of a few, for conservation and preservation, and in response to, at times, widespread support for continued public ownership. These public lands, managed by numerous agencies with a multitude of goals, set the United States apart from much of the rest of the world where private ownership dominates most countries. The future of America’s public lands depends more than ever on collaborative planning and management with both local and national priorities in mind, ideally carried out aside from politics, socio-political boundaries, and historical norms. These priorities are diverse, ambiguous, and at times conflicting—grazing, mineral extraction, timber harvesting, habitat and ecosystem restoration, wilderness preservation, supporting native fish and wildlife, outdoor recreation, and more. The preferences of residents and communities and the desires of recreationists and conservationists living at a distance must be balanced and considered in concert with broader values and issues of national interest. But all these interest groups must understand that should these lands be transferred or sold to states or private parties, they will be forever lost from our public lands system—a loss that will be felt by many but will benefit few.