Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal, Fall 2017

In the dawning years of the 20th century and amidst a flurry of technological innovations, two significant yet seemingly divergent advancements would become inextricably intertwined. Conceived almost simultaneously, the airplane and motorcycle were birthed from humble beginnings. Powered flight evolved from frail and impractical kites, and the motorcycle was an adaptation of the newly invented bicycle. Both captivated the same breed of plucky thrill seekers easily swooned by the visceral sensations of fast accelerations and heavily banked turns.

Antique photographs of those pioneering individuals depict an age of adventure with brave dare-doers clad in similar pieces of functional apparel. From their leather skull caps fitted with metal-framed goggles, to heavy jackets made of waxed canvas or thick leather, such costumes were not dedicated to one pursuit or the other as the pilot and the motorcycle rider were often one and the same. Well acquainted with the need for wind and weather protection, they needed those layers in order to safely and comfortably travel at unprecedented speeds never before achieved. For the motorcyclist at the turn of the century, it also didn’t take long to learn the advantages of an extra skin. The first riders to fly ass over teakettle didn’t always live to tell about it, or ride another day.

Prior to the 1920s, when many bustling metropolitan streets were choked with slow-moving Model T Fords, motorcycle racing was rapidly becoming a popular attraction. It must have been a spectacle to behold as manufacturers like Pope, Excelsior, and Williamson Flat Twin produced motorbikes capable of coaxing just a few horsepower to speeds exceeding 70 mph. Although the racers of the time wore little more than thickly woven wool sweaters, most riders plying open roads opted for the security and comfort of cowhide.

At this same time, aviators were pushing limits of their own. Aircraft advanced quickly in the years following the Wright brothers’ first tenuous forays into the blue in 1903. The German Fokker Eindecker mono-wing airplane took to the sky in 1915 and could reach speeds up to 90 mph. The Junkers J1 was even faster with a max speed of 110 mph, while slower planes like the British-made Sopwith Pup could execute turns, twists, and dives defying the perceived boundaries of physics. With their open cockpits, the pilots within shielded themselves from cold wind and the often spraying oil of a cantankerous engine with the same jackets they wore on their motorcycles.

The connection between plane and motorcycle, pilot and rider, was strong in those early years. Few casual historians recognize the given name of the famous WWI flying ace dubbed the Red Baron. Known to history as Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen, he is certainly better known than his contemporary and fellow German pilot Werner Voss. Credited with 48 kills to Richthofen’s 80, Voss was an avid motorcycle enthusiast. Given a 300cc V-twin Wanderer for his 18th birthday, it served as the wellspring for his love of speed and engines, and likely helped hone his courage and skills as a fighter pilot. Although only a few images of Voss exist, one of the most alluring shows him proudly posed in front of a motorcycle.

In subsequent years, another celebrated aviator would transition from wheels to wings. In 1920, while still in high school, an ambitious but withdrawn young man ordered an Excelsior Big X motorcycle from a local hardware store in Little Falls, Minnesota. Just 2 years later he rode that same motorcycle to Nebraska where he learned to fly. Then 5 years on, the quiet man forever known as Lucky Lindy became the first person to fly nonstop across the Atlantic. Several images have survived the years since showing a smiling Charles Lindbergh sitting atop his Excelsior while wearing a thick tweed riding coat identical to those he often wore in the cockpit.

As pilots and riders began to make names for themselves on race tracks and airfields the world over, so too did the purveyors of the clothing they preferred. One of the most prominent names in aviation and motorcycle apparel, and one much revered even today, is Belstaff of Britain. Founded in 1924 by Eli Belovitch and his son-in-law Harry Grosberg, Belstaff was a cuttingedge innovator in technical textiles. Grosberg’s commitment to creating optimal product led him on extensive travels throughout Europe and Asia in search of the best fabrics and construction methods. Belstaff ’s use of Egyptian waxed cotton quickly became the performance standard for waterproof and breathable garments, necessary qualities in the rainy hills of England.

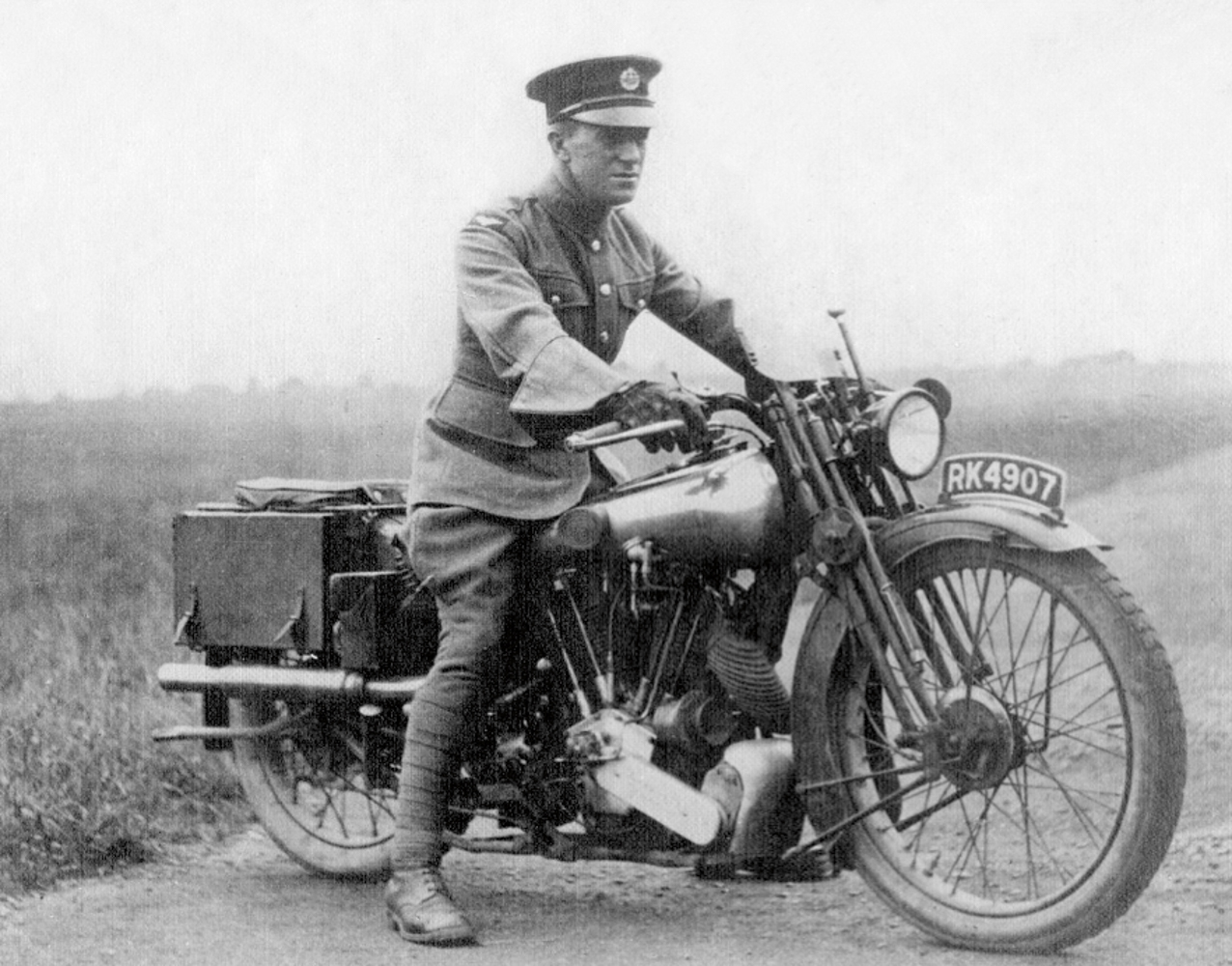

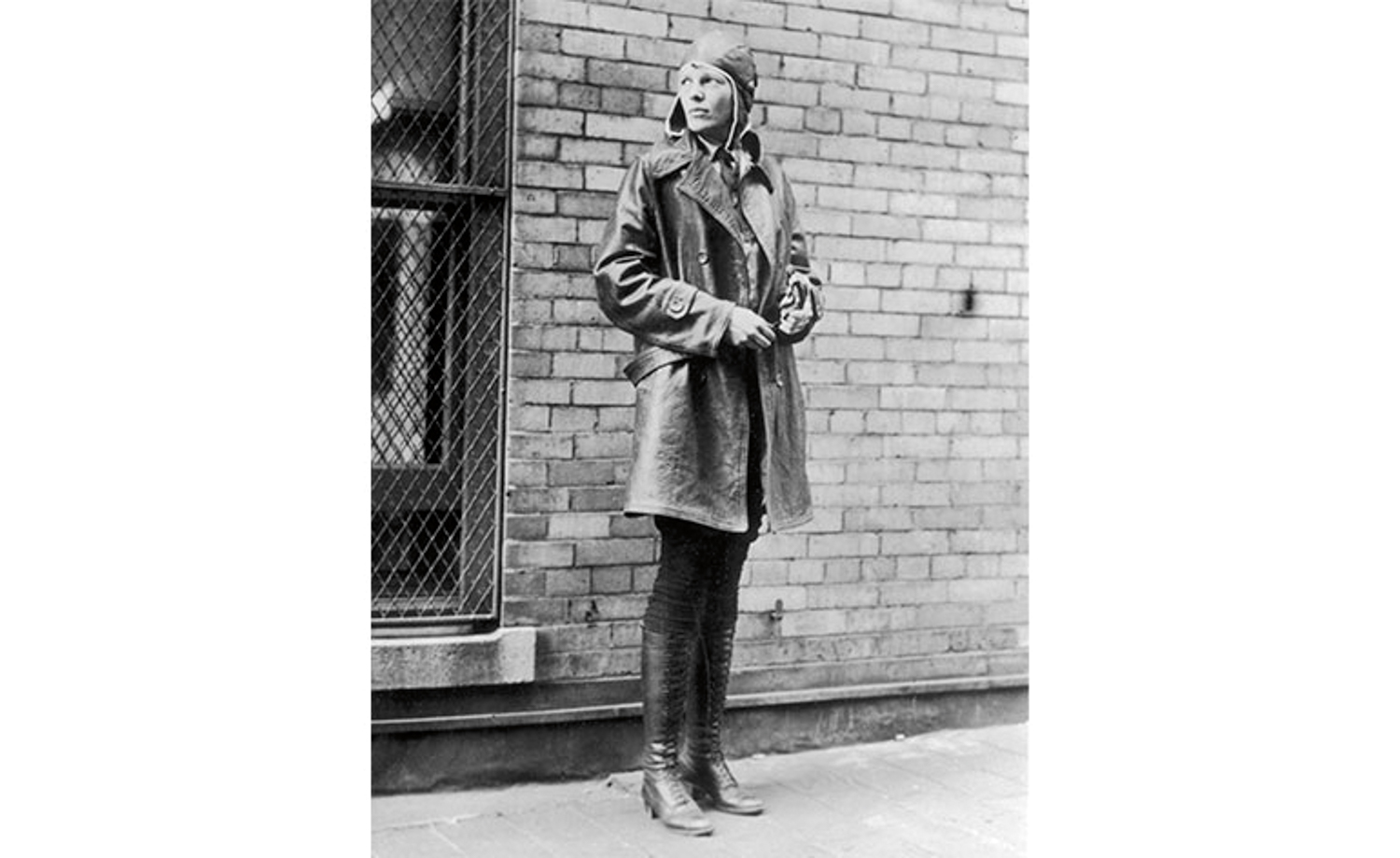

With competitive motorcycle riding taking on various disciplines, from top-speed record setting to grueling off-road endeavors, Belstaff continued to win loyal customers, many of them of celebrated repute. Writer T.E. Lawrence of Lawrence of Arabia fame was an early Belstaff user and a fanatical motorcyclist. Sadly, it was to be his demise when he lost his life in a crash in Dorset, England, in 1935. Perhaps one of the most high-profile wearers of Belstaff goods, and furthering the connection with aviation, was the now-legendary aviatrix mysteriously disappeared—Amelia Earhart.

Shortly after Belovitch and Grosberg’s rise to prominence, another player entered the motorcycle-apparel market. The illustrious Barbour brand was formed in 1894 by Scotsman John Barbour, but came to fame much later. Originally established in Britain as a supplier of fine oil-cloth textiles, it wasn’t until John’s grandson, Duncan Barbour, got involved that the name became synonymous with motorcycles. An avid rider himself, Duncan quickly recognized the potential of waxed canvas and began pursuing advanced jacket designs to meet the demands of the growing two-wheeled community. By the mid-1930s, Barbour was extolled throughout the motorcycling world as the premium product to have.

Today Barbour and Belstaff have done well to leverage the popularity of their brands with savvy ambassadorships and marketing strategies. In the years since his untimely death in 1980, Steve McQueen has been elevated to near demigod status. The consummate man of action, McQueen was renowned for his love of motorcycles and an expert ability to ride them. Both Barbour and Belstaff lay claim to outfitting McQueen over the years and in doing so have drawn the collective adulation of a consumer base hoping to channel his quintessence of coolness.

Continuing in that vein, Belstaff launched an extensive marketing campaign in recent years with Ewan McGregor as their primary model and spokesman. Known throughout the world for McGregor’s Long Way Round and Long Way Down documentaries chronicling his extended motorcycle journeys around the world, his fame has gone a long way toward refreshing Belstaff ’s place in the spotlight. So vaunted is the classic styling of a Belstaff jacket, you’re more likely to see one worn on promenade in the streets of London and New York than you are pushing through the muddy green lanes where it was originally intended to be used.

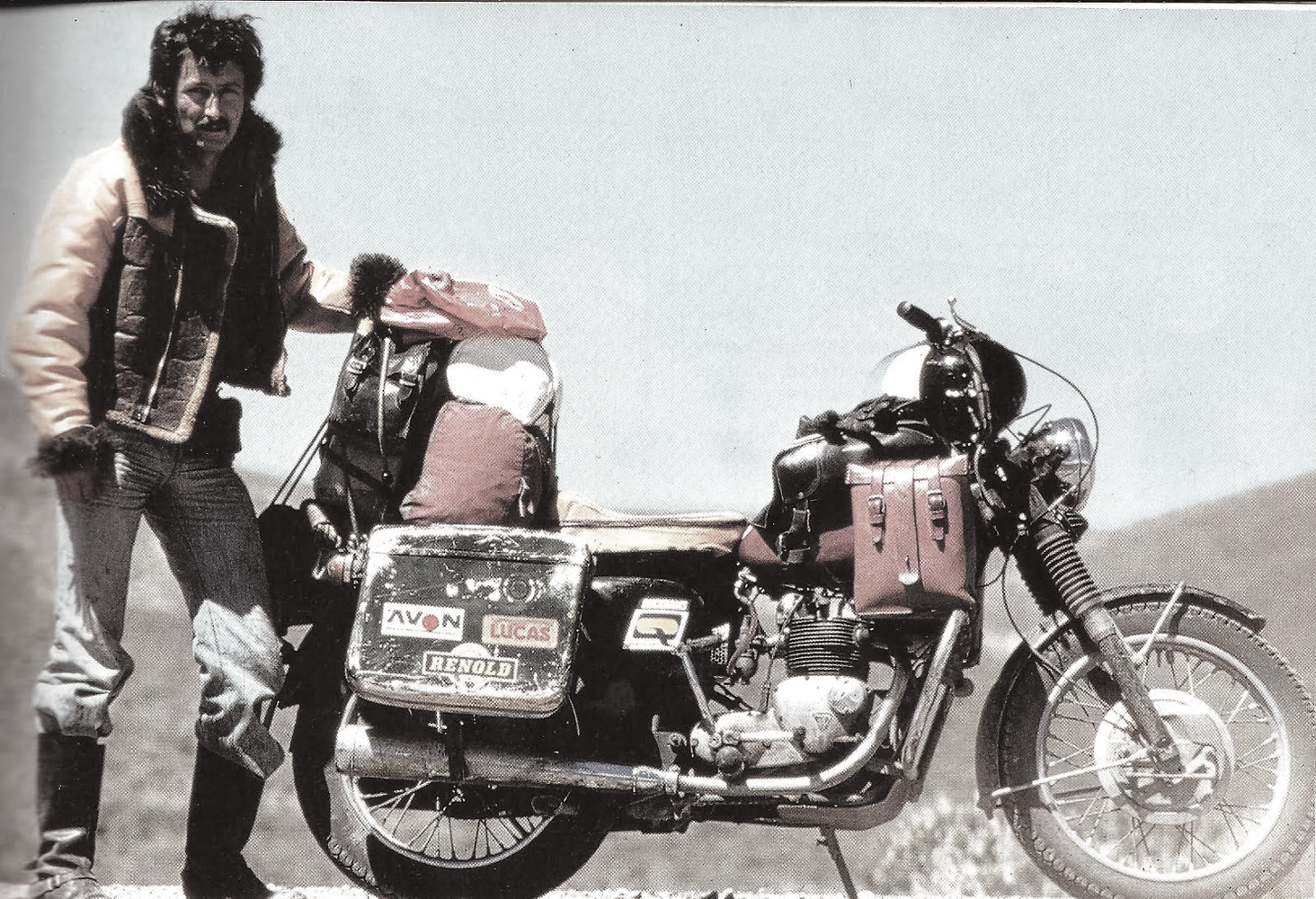

Over the course of a century, the jackets designed for pilots and loved by motorcycle riders have become stalwarts of fashion on and off the bike. During the Second World War, thousands of airmen in combat theaters around the globe were issued leather flight jackets, most of them highly prized by the brave men who wore them. When Ted Simon completed his circumnavigation of the world atop his Triumph, he did it in a leather jacket styled after those used by WWII bomber pilots. Made by dozens of manufacturers under a handful of official government-designated model numbers, these heavy leather jackets, often emblazoned with special insignia, became collectibles, family heirlooms, and depending on the men who flew in them, even coveted by museums.

One of the more renowned manufacturers of governmentcontracted flight jackets was the Schott company based in New York. The first to put a zipper on a leather jacket in 1925, they were commissioned by the U.S. Army Air Corps to produce a variety of outer layers from fleece-lined bomber jackets to peacoats. Schott’s products went on to be worn by the history makers of WWII like the Tuskegee Airmen, the illustrious fighter squadron with one of the most successful records in all of air combat.

Before and after the war, Schott’s leather jackets were popular with the two-wheeled set, but it wasn’t until 1953 when a young Marlon Brando appeared in the acclaimed film, The Wild One, that the motorcycle jacket took on a persona of its own. Central to his portrayal of a disaffected gangster was Brando’s Triumph Thunderbird, but more importantly, his black leather jacket with the name Johnny embroidered on the shoulder. Made by Schott and sold as the Perfecto, it would remain emblematic of counter-culture for generations to come, and not just amongst those prone to sit astride a motor.

The Perfecto and its countless knock-offs have been worn by every stratum of society from dropouts to movie stars, along with musicians like Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders. James Dean wore one, as did Bruce Springsteen, their images edgy but respectable. Iggy Pop, Billy Idol, Joey Ramone, and the most rebellious of rebels, Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols wore iterations of the Perfecto, but with the same stylistic proclamation—the black leather motorcycle jacket is the mark of the ultimate bad boy (or girl).

So pervasive was the collective perception of the black leather jacket and its association with grifters, hooligans, and general misfits, that when the producers of the wholesome TV show Happy Days decided to give their star character a leather jacket, they chose a more tame brown version, eventually swapping it out altogether for a red cotton windbreaker. Fonzie’s famous leather jacket would eventually take up residence in the Smithsonian. It wasn’t until the arrival of Tom Cruise in his role as a Kawasaki Ninja-riding Navy fighter pilot in the blockbuster Top Gun that the leather jacket reappeared as a must-have fashion accessory for the everyman. Once again the lines between aviator and rider blurred.

The modern motorcycle jacket has taken on many forms over the last 3 decades. Some retain the vintage aesthetic of the early years while others, particularly as of late, resemble space suits more than riding outfits. Form and function are often at odds with the protective riding jacket, but a few innovative manufacturers have managed to bridge the gap. Technical apparel has evolved of late with Kevlar and ceramic-impregnated fabrics, reactive crash armor, waterproof and breathable membranes, and internal warming and cooling layers.

One element of motorcycle apparel remains unchanged— whether made of nylon, leather, or waxed canvas, every jacket looks best when coated in dust from the road. Evocative of those amazing men in their flying machines, and made iconic by adventurers on two wheels, the motorcycle jacket, even today, is the costume of the undaunted.