As we approached the Bainbridge Island ferry terminal, the young girl inside the ticket booth opened the window and hung her head out. “Hello, I’d like to pay for me and the guys behind me,” I said. Momentarily nonplussed, her eyes gazed from me, down to our vehicles, then back up to me. “Well,” she said, “You’re the size of a smartcar, but you only have…” she craned her neck to double-check, “three wheels. So, I guess that sort of makes you a motorcycle.” And with that, our two Ural sidecars, loaded up with what could have easily been a Toyota RAV4’s worth of supplies, entered the holding lot. We passed row after row of cars before sliding down to the front of the preferred motorcycle loading lane. When the ferry arrived, we were the first to board. It’s not often the case, but sometimes being a complete vehicular oddity can really work to your favor.

Earlier that day, we arrived at a delightful nondescript industrial park in Redmond, Washington, to pick up the sidecars from Ural’s North American headquarters. Nick Johnson, founder of the adventure motorcycle blog Ride & Wander, put the trip together and had invited a small group of us to come along. Ben Lamprecht, a San Francisco-based biotech engineer and general motorcycle fanatic, piloted one of the sidecars. And I, in a bid to justify my inclusion, overstated my writing abilities for the opportunity to come along. Nick’s brother Kyle, a Seattle-based photographer, would manage visual documentation of the trip.

The plan was sparse on details, but rich with potential. We intended to make our way out to the Olympic Peninsula and post up at a secluded A-frame cabin outside Forks, and from there explore the multitude of logging roads that crisscross that part of the state like the ribs of a wicker basket. Our trip also coincided with the start of the spring run for steelhead trout, which, generally speaking, meant very little to us—except for Kyle, to whom it meant a tremendous deal. When he arrived with a handcrafted collapsible rod in hand, a pair of Filson waders, and a level of sanguine enthusiasm I had no idea could be aroused by the notion of fishing, it became clear we’d be spending some time down by the river. Thankfully, there is no vehicle better suited for scrambling around on rocky river banks than a Ural sidecar.

Outside the hangar-sized garage at Ural headquarters, the chief mechanic gave us a quick rundown of the two models we’d be riding. The first was a tundra cameo 2015 Gear-Up. This classic 2WD workhorse is the perfect example of Ural’s time-honored, Soviet-hardened agrarian grit. As far as sidecars go, the Gear-Up is the weapon of choice for gray-bearded, wild-eyed men of the mountains. The second rig was a terra-cotta colored cT, a brand-new bike for Ural. This slimmed down, single-wheel drive model is designed to be lower, lighter, and easier to handle than the Gear-Up—a configuration intended to be a little more appealing to the wax-bearded sartorialists of the city.

Both vehicles are built tough-as-nails, almost entirely out of metal, with hardly a piece of plastic on them. When we cautiously asked if it would be all right for us to take them off-piste, the mechanic said we’d be fools if we didn’t. “These things are practically indestructible,” he said. “Don’t worry if you bring them back with a few nicks or dings, we’ll just pound it back into shape and slap some paint on it.” This blasé attitude toward property damage is definitely not the usual line one hears when taking out a press bike. And true enough, upon closer inspection, the faint remnants of past mishaps and miscalculations could be discerned underneath a fresh coat of paint. After taking a few turns in a nearby parking lot to get acquainted with the sidecar’s unique steering characteristics, we were cleared to take them out for the weekend.

When the ferry was docked and the ramp lowered, our two Urals were also the first vehicles to disembark. Traveling by ferry is completely common around the Puget Sound, but there is still something particularly grand about starting a trip in this fashion. When your mode of transportation requires another mode of transportation to get where you’re going, it can make even a modest weekend trip feel like a proper adventure.

The first leg of the trip had us skirting along the northernmost section of U.S. Route 101. The sun was out, but the coastal air was cool and thick. The salty smell of ocean brine filled our helmets whenever we passed a cove or inlet, leaving us with the sensation that we had just slurped down an oyster—which was great if you enjoy oysters.

While long stretches of highway are often the most monotonous part of any motorcycle trip, they can be somewhat of a challenge when riding a Ural. This is because the bike’s 749cc boxer-twin engine, a piece of hardware that has scarcely been updated since the Soviets first “acquired” the designs from the Nazis in 1940, can only muster about 41 horses. To make matters worse, Urals are purposely built to be “big-boned” and weigh in at a husky 700 pounds. With so much heft and so little oomph, highway travel becomes a serious game of momentum conservation. Like master tacticians, we scanned the road ahead for any change in grade that could aid or hinder our progress. Pouring on the gas during a slight downhill might push the needle from 75 mph to 85 mph, but a poorly timed downshift on an uphill could quickly reduce our speed back to 50 mph for quite awhile. In this way, our two sidecars yo-yoed back and forth as we each tried to dial in Newton’s first law of motion.

From Port Angeles the road to Forks heads inland and winds through the foothills of the Olympic Mountains. With the sun starting to set and a foreboding cold creeping into the valley, we found ourselves racing along the crooked contours of Lake Crescent. The surface of the water was as still as glass and reflected like the portal to an inverse universe. Towering mountains surrounded us, appearing to stretch down into the lake’s depths with an endless abyss of twilight purple sky at its very bottom. Here the road began to twist and turn and the Ural’s bizarre steering revealed itself in full.

While a typical motorcycle is able to gracefully bank through a turn with just a bit of counter steer, cornering with a sidecar is a far more physically involved process. Urals have fixed axles and are unable to lean, which means the only way to get around a turn is to manually steer through it using the front wheel. A seasoned rider might call this an “engaging experience,” but to novices like ourselves we were inclined to call it “a real son of a bitch.”

The whole thing goes a little something like this. Steer to the left and the sidecar starts dragging like an anchor on your right. Steer to the right and the sidecar will start to feel light, as if it were about to pop up and over your head. The only way to make it around the corner and keep speed up is to hike off the side of the seat like a deckhand on an America’s Cup sailboat. This goes for the person in the sidecar too, who, during these times, becomes more of a participant than a passenger. After the initial gut-wrenching terror wore off, we started to loosen up and get into the groove of things. Before the end, our clenched teeth had slowly worked their way into smiles.

None of us could really remember the last 40 miles to the cabin. It was an eye-watering blur of wind and cold. With the last ounce of light draining from the sky and our night’s shelter still an unknown distance away, we slipped into a frenzied, animal-like dash in a final bid to escape the approaching night. We didn’t know where we were going, but we were sure as hell going to get there fast.

We eventually found the road that led to another road that led to a dirt trail that led to the cabin. However, it wasn’t until we were inside and got the wood stove rip-roaring like an atomic reactor did we started to feel human again. The cabin had one legitimate bed, a narrow couch, and a variety of other pillows and mats that one would struggle to categorize as “bedding.” Thankfully, full-body exhaustion can do a lot to smooth out the rough spots and we had little trouble getting comfortable. Although it wasn’t long after my eyes closed that I started carving those far-out corners again in my dreams.

I woke up a little before dawn to the sound of one of the Urals revving to life. Outside, Kyle was already suited up in his fly-fishing regalia and using the light from the headlight to string up his reel. Like the crow of a rooster, the sound of the engine idling roused us into action and we slowly got dressed and shambled outside for a scouting run down to the river.

It had been an abnormally dry year and the water level was far lower than normal. In order to reach the river we had to cross a minefield of football-sized rocks. When we got to the edge I stopped and leaned over to Nick, “So, when they said it was okay to take them off-pavement, did they mean this?” Before Nick could respond, Ben and Kyle had blitzed through the trees and gunned it out into the rocks. “I’m sure it’ll be fine,” Nick said, and away we went.

Our Urals clamored, rattled, and rolled over the loose rocks, but never lost traction. Their engines are known for a nearly flat torque curve, so even at a crawl the back wheel has plenty of bite. As we plodded forward over the rocks, we could feel each wheel searching for proper footing. Like a crab on the beach, the experience felt more like scuttling then riding. On only a few rare occasions did we pop our Gear-Up into 2WD mode, more out of curiosity than necessity. The single-wheel drive cT seemed to be more than capable of handling the terrain without an extra-powered wheel. We eventually reached the river and deposited an enthusiastic Kyle along its banks. The rest of us, with equal enthusiasm, did the next natural thing, which was to find a place to do a water crossing.

I would say that 90 percent of water crossings are needlessly contrived spectacles. I would also say that our actions that day were in strong support of this presumption. Nevertheless, they are an integral part of motorcycling lore and an essential right of passage. They are also a ton of fun, especially when there is practically zero chance of falling over. We went a good distance upstream, so not to disturb Kyle, and found a suitable section of the river. Despite their utilitarian design, Urals have a conspicuously low tailpipe configuration, which gave us a fleeting moment of pause. However, we all agreed to just “not get stuck,” which is delusional off-pavement speak for “don’t let off the throttle.” So we backed up, built up a little steam, and charged in.

A sidecar displaces a lot of water. Like a gas-powered flume ride, we kicked up a magnificent spray that nearly engulfed us as we barreled through the shallows. When we arrived at the mid-river sandbar we were heading for, we made two important discoveries. The first was that the temperature of the Bogachiel River in March is as close to liquid ice as the laws of thermodynamics will allow, and secondly, that we had taken on quite a bit of water. Thankfully, there is a small drainage hole underneath the floor mat. Apparently, this sort of ill-conceived amphibious usage was something Ural engineers had anticipated. We spent the next couple of hours racing about the riverbanks trying to “not get stuck” before finally returning to collect Kyle.

He was just as stoked about being there as he was when we dropped him off, and it took a bit of cajoling to get him out of the river and back to shore. “Man, that was fantastic. What a great morning,” he said as he started to break down his pole. Being completely unfamiliar with the unspoken etiquette of fly fishing, I asked the first dumb question that came into my head, “So, did you catch anything?” Clearly he had been asked this before and was ready with a response, “You know, sometimes there’s fish in the river and sometimes there isn’t, but that’s not really the point.” Out of sheer contrarian habit I contested, but eventually came around to see that it was the exact same thing we were doing. Some guys ride motorcycles because they want to win trophies, but most of us do it just to enjoy the ride.

That afternoon we stopped at a classic all-American burger stand where we smudged up a map with greasy fingers in search of some dirt roads. Maps and six-bar cell service are excellent resources, but when it comes to sussing out the best riding roads in an area, nothing beats finding an affable old guy who has been living “around these parts” all his life. Such roadside sages are often filled with real gems of local information—so long as you’re willing to mine through the tall tales and meandering anecdotes to get to them.

We were fortunate to attract the attention of just such a personage, named Bob, who was handing out Xeroxed flyers for a motorcycle-themed campground he called Cycle Camp. After telling us a bit about his business, he gave us the inside scoop on a nearby logging road that led up to a recently cleared hilltop vista point. We thanked him for the tip and wished him luck on his decidedly niche venture.

We turned off the smooth surface of the 101 and onto a crumbly, loose gravel road that wound its way up into the mountains. Most logging operations shut down for the weekend, but you never know when a 40-ton cloud of dust might come flying around the corner, so we kept a careful eye out. The deeper we pushed into the forest the closer the pines grew, until the canopy of needles overhead became so thick that only a few pools of light dotted our path.

While our rock scrambling down by the river showed off the Ural’s technical ability, on long stretches of dirt road is where the machine is truly at home. Tearing down mile after mile of dirt track, bounding over washboard ruts, and charging through muddy puddles is exactly what these vehicles are designed to do. On the dirt, the reduced traction takes the edge off the sidecar’s somewhat sticky steering, allowing the vehicle to gently “float” around corners. And unlike riding an adventure motorcycle, there’s no lurking paranoia of washing out the back wheel or keeling over for no apparent reason. Here, more than anywhere, it becomes clear that a Ural has the spirit of a dirt bike, but the stability of an SUV.

It was late in the day when we finally arrived at the bottom of what we would later refer to as “the big climb.” Apparently, logging companies don’t waste time building switchbacks; this road seemed to run straight up the side of the hill. The surface was hardpacked at the bottom, but toward the top it looked like a crumbly mess of churned earth and coarsely chopped mulch. We would need to build up a good deal of speed to make it up without losing momentum.

Experience has taught me that the longer you sit looking up at a climb, the more horrifyingly elaborate your visions of failure become. At first glance, you can register a vague notion of doubt, but linger around at the bottom for a few minutes and your mind will concoct all sorts of crazy scenarios that end with your vehicle cartwheeling end-over-end back down the hill. That is why it’s important to act quickly and decisively and not give in to hesitation. Fortune favors the bold, which is why I wasted no time in electing Ben to go up first. He had been driving like a madman all afternoon and I knew he had just the right clarity of mind to make it.

So up he and Kyle went. There was a brief moment of concern when they transitioned to the loose stuff near the top, but despite the plume of dust that came out the back, they just kept chugging away. This proof of concept was a heartening sight indeed, and just what I needed to kick myself into gear. With a running head start, we followed after them.

It was steep but smooth most of the way up; things began to get a little bouncy once we hit the hanging cloud of dust. A steep hill climb is difficult, but throw in low-visibility and the whole experience starts to feel more like a theme park roller coaster than a motorcycle ride. The road eventually leveled off and we emerged from the cascading particles of dust and ascended into the golden rays of the afternoon.

The hilltop had been entirely cleared, which gave us a nearly 360-degree panorama of the surrounding area. White-capped mountains towered all around and were connected by a lush evergreen carpet of pines that filled the valleys. It was a tremendous sight on its own, but enjoying it with such good company is what made the moment stick.

Herein lies the sidecar’s greatest feature: the shared experience. Even if you ride in a group, motorcycling is almost always something you participate in as an individual. People around you may be experiencing something similar, but it’s never quite the same. In a sidecar, the other person is sitting there right beside you, enjoying everything in tandem. This perspective changes the whole dynamic of the ride by transforming a solitary activity into a group event, allowing you to have more fun than you ever could alone. Whether you are you are rocketing up a squirrelly climb or plowing through an icy river, there’s nothing quite like being able to turn to the person next to you with a devious grin, and say, “Whoa, let’s do that again.”

These Photos were taken by Kyle Johnson and are just a small sample of his amazing work. To see more, check out his Instagram account here or his website at KJPhotos.com

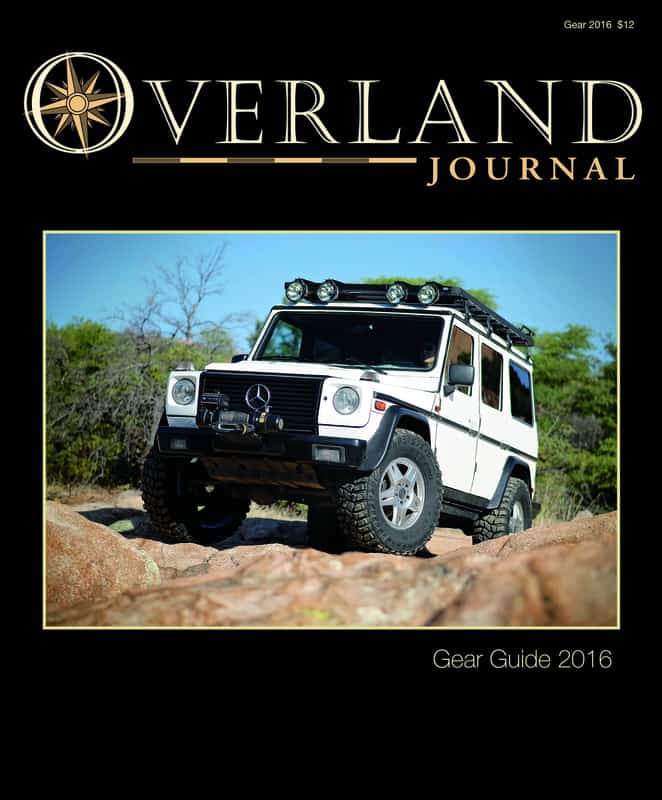

This story was originally published in the Gear 2016 issue of Overland Journal, the publication for environmentally responsible, worldwide vehicle-supported expedition and adventure travel. To find out more or purchase this issue, visit their website here.