We had turned off the highway miles ago, following what our Garmin claimed to be a road. Piles of red dirt were tucked to the side of sandy path no wider than the van, waiting to be packed down—a project unfinished. We were still very new at this, having just left the U.S. yesterday morning, and we were the only gringos around for miles. A day in from the first border crossing of what would be eleven more in our casa-rodante, our car-house, we were looking for a campsite at a partially deserted beach on the Baja peninsula of Mexico. Shanties were sparse, and in the daylight, they didn’t look like places people could live. Later, when their lights winked in the dark, I counted five, spaced widely, leading north. I watched the lights and tried to picture who might be sleeping inside. I wondered if any of them would want to talk to us. We needed them to talk to us.

The happy-go-lucky part of our journey was great: vanlife was fun. We were fresh off a successful crowd-funding campaign. In the U.S., we camped every night and spit our toothpaste out wherever we wanted. Friends met us in every city on the West Coast, and the National Parks were delightedly everything we’d seen in pictures. But an uneasiness loomed in the van that we didn’t want to talk about: when were we going to start our project? The money we’d raised was earmarked for a portraiture project that we had mapped out with the lofty goal of connecting with another culture on a deeper level than most do when traveling. To us, four post-grads of film and photography, it meant driving south–far south–with a small photo printer so we could give a copy of the picture to each person we photographed. We had enough gear and supplies to last us all the way to Ecuador.

Northern Baja’s vacancy leaves room for thoughts to unravel and spread themselves into the desert for miles. There’s nothing else. The hours as a passenger in the van were also taking apart my head and what was obvious was this: I had no idea how we were going to do this. How the hell do we get people to trust us to photograph them? As strangers, as extranjeros? What should I say? Would they understand my broken Spanish? I was nervous in a way that made me brave, and I wanted to meet someone new ASAP. Tomorrow. I wanted to force the hand of whatever was going to happen so I wouldn’t be nervous anymore (turns out that never went away). When I woke up, I would walk down the unfinished red road, camera in hand, until I saw someone I could approach. I had no plan on how to discern who was approachable, but I ignored that part. If I had to go careening in to get this thing started for myself, so be it. Control wasn’t important.

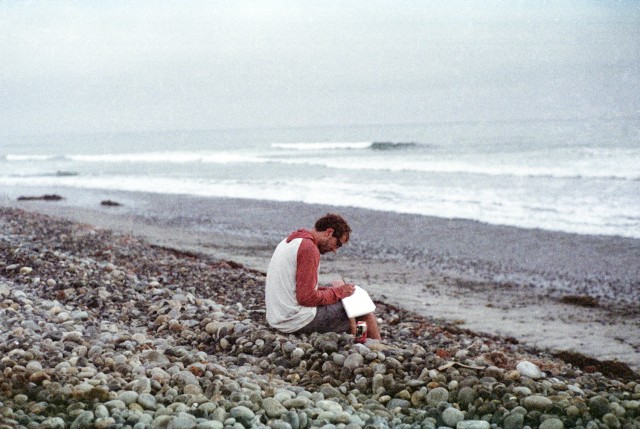

But I wasn’t all guts. The next morning I took Aidan with me, who spoke better Spanish. The fog rolling in from the ocean tampered my feelings down the way fog does—everything was quieter.

Alfredo stood outside his structure that was pieced together from corrugated plastic and pallets, shifting his weight back and forth and trying to be casual, but also looking at us again and again. I couldn’t imagine there were a lot of visitors out here, and he seemed uncertain. We smiled and said hello, and that was all he needed–we were immediately inundated in his story and invited to sit. His world was like this: gather rocks from the beach. Sell them to a middle man. Middle man sells them across the border for landscaping in the U.S.—as far north as Washington. Each shanty has their “territory;” they didn’t work together when they gathered, but they didn’t work against each other, either. He picked the stones up and showed them to us, running them through his fingers and onto the ground again. Workdays had a type of rock assigned to them: on this day, smooth black mediums. On another day, small yellows.

Hot water was offered to us under a covered area in front of the structure where the rest of his family was milling around or finishing morning chores—a porch. As I spooned the instant coffee into my mug, my hand froze. Shit, the water, I thought. It was too late, though. There was no way to politely hand back the drink that would probably-maybe-surely do its worst to my gringa stomach. I smiled at Alfredo’s wife, and took some cautious sips as if there were going to be immediate effects.

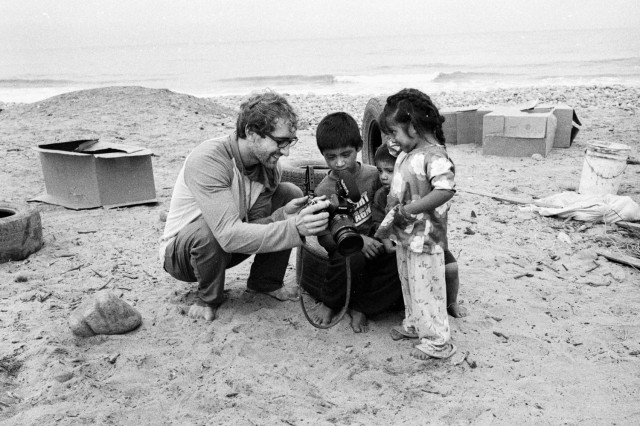

There was nothing smooth about our interaction after that. It remained friendly, but a script for explaining our project in a way that makes sense across languages doesn’t exist, and I’m pretty sure when people agreed to let us photograph them they didn’t really know what they were agreeing to. There was just no way of saying, “I want to make your portrait and give you a copy; I have a printer in my van, and I will be leaving in that van in probably ten minutes to continue driving to Ecuador from your town here in Mexico/Belize/Guatemala. Oh and also I’m traveling with three other people. All guys. They’re photographers, too.” I could see so many of their faces: Uh-huh.

Organizing a family photo is the same in every culture, though: someone’s looking off in the distance while one of the kids is crying, while someone else is blinking with what has to be all their might. With the seven members in Alfredo’s family, the odds of someone both smiling and looking at the camera was 2/7. Afterwards, I noticed Alfredo’s wife frowning at the copy of the photo in her hands. “Do you like it?” I asked, not really knowing what else to say. “Si…” she replied, and I realized baffling this encounter must have seemed to them.

Alfredo couldn’t have realized how important talking to us was. When we walked down the road that morning, we were walking towards our fear, and letting it come out and bite us so we could get that part over with and see what happened afterwards: our first encounter was awkward, but it represented something to us that we carried with us for the rest of our project, and it left Alfredo’s family so bemusedly joyful in a way that we saw many more times as we traveled through Latin America. When Aidan photographed Alfredo’s daughter, Alfredo told her, “Now a little piece of you is going to the United States.” I had said control wasn’t important, and the amount of empathy I felt upon hearing his words spread through me as a physical reaction, making it hard to breath. I decided that figuring out the Great Significance of our project, right then and there, wasn’t going to happen. And it didn’t need to. We were new.

Read more from the Vanajeros [HERE].