The centuries-old mansion on Puebla, Mexico’s central plaza had been converted into a restaurant on the bottom floor with new apartments above. We sit in the living room of one of those apartments on the second story. With its towering ceiling and decorative tile floors, it surely used to be the salon of high society. Today, the room is part of an unusually laid-out Airbnb.

Eric’s cousin and her husband are visiting us in our rental while we enjoy exploring their city on our way through interior Mexico. Tonight is a date night for Eric and me, and our family members have volunteered to watch over our five-year-old son, Caspian, while he sleeps. But the conversational pleasantries have evaporated, and our cousin is choking back tears.

The reason? Because the country you are born into directly impacts how much of the world you’ll ever get to see and how much it will cost you to see it.

Let me explain.

Reframing the Conversation

Eric and I are used to being asked about money. “How can you afford to travel full-time?” is one of the most common questions we’ve heard over the past nine years, and we answer it openly. As we prepared to drive around the world, a large part of our focus was on the money: paying off debt, figuring out what to do with our five internet-based business projects, and ultimately, making sure we could financially sustain a trip of this magnitude.

There was one thought that never crossed our minds. Would our passports allow us access to enough countries to actually get around the world?

It didn’t cross our minds because we are United States citizens with United States passports. With a US passport, we can enter 186 countries visa-free or apply for entrance when we arrive. Only 41 destinations worldwide require US passport holders to receive entry approval beforehand.

This makes the US passport the seventh most powerful passport in the world. For citizens of countries without passport power, their international travel options and experiences differ from ours.

Inexplicably Unequal

That night in the weird mansion living room in Puebla, we were talking about family. Eric’s mom is in her 90s and can no longer travel. She lives in Seattle. Meanwhile, Eric’s cousin wants to see her aunt one more time on this side of heaven.

“We’ll help you,” Eric and I exclaimed without hesitation. “We’re happy to help with travel costs so you can fly to Seattle.”

“You don’t understand,” Eric’s cousin choked out between tears. “I can’t.”

“Why can’t you?” we responded, dumbfounded. This cousin is a rock in the family, the one everyone goes to for advice. She and her husband own a large home in a gated community. Their three children are college-educated with blossoming careers. Why wouldn’t the United States government let her visit her elderly aunt for a week?

It was a painful subject, so we moved on. I insisted I would look into it. Surely we could get her a visa to visit Seattle.

True to my word, I started researching US tourist visas for Mexicans online. It took lots of clicking in circles to figure out what type of visa would be needed (B-2: tourism, vacation, pleasure visitor).

For that innocuous visa, the United States government requires an interview. So I selected the Mexico City consulate, which is closest to Puebla.

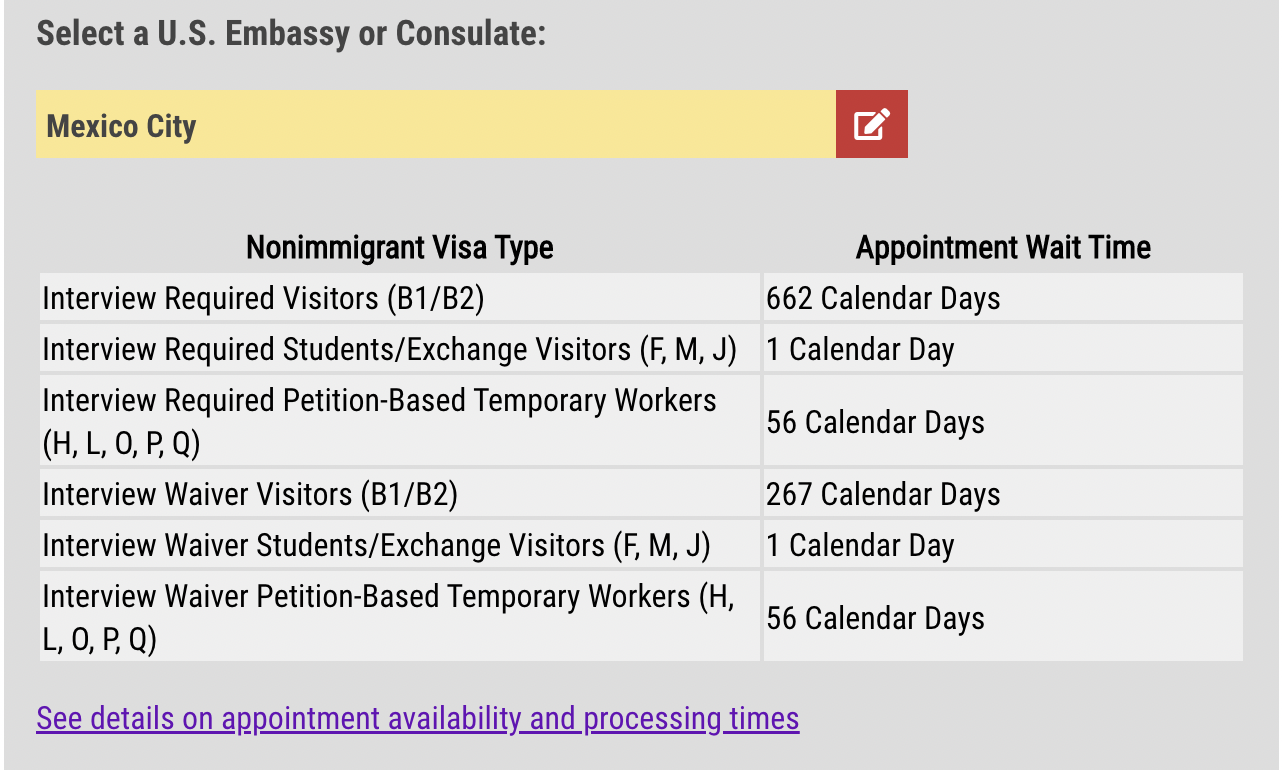

Next, I researched the wait time for an interview.

It’s 662 calendar days.

Eric’s mom turns 91 next month.

Privilege in a Passport

Not long after our stay in Puebla, we were at a dilapidated beachside restaurant in Isla Aguada, located on the coast curving north to Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula. There was another child with his parents, a human magnet for gregarious Caspian. We started talking with his father, who hailed from a European country.

We talked about points of interest in the United States, and he exclaimed how much he’d love to see them for himself. “You’re already in Mexico,” we responded with excitement. “You should visit.”

“I couldn’t go without my wife,” he responded. “She has a Mexican passport.”

As we have made our way through Central America over the past year, we have become attuned to our privilege as US passport holders. We learned about our overlanding friends (who hold a British passport and a Swiss passport, respectively) who were ruthlessly detained for two nights at the United States border with their beautiful two-year-old daughter. They were separated into two rooms: one for men, one for women and children, all because of a computer system error (see the upcoming Spring 2023 issue of Overland Journal for the complete story).

When it came time to ship our vehicle from Panamá to Colombia, we met another overlanding couple with dreams of traveling in South America. She has a Canadian passport, while he has a South African passport. Like us, she can get a Colombian visa on arrival by virtue of her origin. But he had to apply for a visa beforehand—and his application process was a mess. She had to go alone when it came time to fly to Colombia to get their vehicle out of the shipping container. The visa situation is not resolved as of this writing. I hadn’t thought about any of this before. I was cocooned in my own experience, eagerly planning our drive around the world and tackling the challenges that presented themselves on the way to our goal.

But I never considered the potential obstacles inherent in holding a particular passport, your travel limited simply by the country of your birth. For those of us with a powerful passport, it’s time to direct our attention to the experiences of our global neighbors who want to travel internationally.

The Henley Passport Index

I’ve shared real-world stories of family and friends impacted by their passports. But the best empirical data source for comparing passports and finding out about visa requirements is the Henley Passport Index. This resource allows you to examine the visa access granted by your passport and a list of countries you can enter visa-free (or with a visa upon arrival) versus which countries require an application for entry and approval in advance.

Users can find this information for any country. At a glance, here is a comparison between the passport power of the United States, Canada, South Africa, and India:

Dominating the Henley Passport Index, Japan can enter most destinations visa-free (193 out of 199 countries). At the bottom of the list, Afghanistan passport holders can enter only 27 destinations visa-free.

Visa Application Time and Costs

You might be thinking, “So what?” here’s a difference between passport holders who have to apply for a visa versus those who don’t. It’s only a visa application, a formality, right? Not necessarily.

Visa applications require time and money, and the results are not guaranteed.

What if my mother-in-law became ill, and Eric’s cousin wanted to rush to her bedside? She couldn’t because the consulate’s wait time for a B-2 visa from Mexico is 662 days.

What if a doctor in India wanted to attend a global health conference to share data on endemic diseases in their country? If the conference were held in Switzerland, Germany, France, or the United States (or any number of countries), then the doctor would need significant time to acquire a visa to attend, likely missing the chance to exchange ideas and knowledge with colleagues from around the world that could impact all of us. Unfortunately, this is not a hypothetical example. The impact of passport power on global health is widespread and has been written about persuasively in Forbes.

And what about the financial cost? Each visa requires an application fee. A B-2 visa from Mexico currently costs $160, a significant sum for a country with a median annual household income of $13,989.

After all the preparation required and the cost of applying, a traveler’s fate is often in the hands of a single official and subject to a country’s immigration laws, no matter how unjust. It is not unusual for visa applications to be denied. The traveler can give up or pay to apply again.

Treatment by Officials

However, that may not be the lowest blow. The lowest blow is dehumanization.

In her opinion piece for the Guardian, Nesrine Malik writes,

The passports at the top of the Henley index allow the holder to visit almost 200 countries without securing a visa in advance. Those lower down, like the Sudanese one I was born with, must pass through the eye of a needle before being permitted to enter the majority of countries. Applicants face almost unscalable walls of bureaucracy and suspicion, comical demands for paperwork and, often, humiliation and refusal…

Having a low-ranking passport means its holder is under constant threat of plummeting down trapdoors in the middle of a journey. A visa detail overlooked by a border official meant I was summoned, having just landed in Riyadh, into a room of angry Saudi border officials who scolded me for this oversight, and sent me back on the next flight. I wasn’t allowed to leave the airport until I had paid the price of the return flight, which took all the cash I had…

I once sat, flinching, next to a trembling elderly South Asian woman in a wheelchair while she was being yelled at in secondary processing at a US airport for not being able to speak sufficient English to answer questions about who she was visiting. Whatever work her family had put into securing her entry to the country had been wiped out by a single new arbitrary requirement.

The article is worth reading in full if only to grasp an experience many of us will never have to endure due only to global politics, colonialism, history, and government policies far beyond our control.

What Should We Do with This Knowledge?

If you have spent your life in one country without traveling, it is tragically normal to develop an “us versus them” mentality. People from a specific country may become no more than a caricature. Travel rearranges our understanding not just about other places but about other people. A few bad actors never represent the character of an entire nation.

How heartbreaking it must be as an Afghan to want to travel the world as much as I do, with the impossible bureaucracy in the way.

So what should we do about it? Is there anything we can do about it?

Begin with Empathy

Never again will anyone have to endure my ignorance. They will never have to face my “of course you can” attitude, unsure how to explain their situation to me. Because now, I know the color of their passport determines their access to the world, and that access is likely different from mine.

Be a Voice

I don’t know what the future holds or in what circumstances you or I will find ourselves. But I’d like to think that if we’re ever confronted with injustice or cruelty, we will have the courage to speak up.

Though a small gesture, this article is a starting place for me to give a voice to whom no one is listening.

Advocate

I wonder if I was a wealthy political donor if a call to my representative could probably get Eric’s cousin a visa to Seattle. Maybe. But I’m not a wealthy political donor, and I’m guessing you aren’t either.

If this issue is important to you, you could join or contribute to any number of immigrant rights groups. That group advocacy could make a difference for visitors to your country. Regarding the global picture, it’s challenging to envision substantive change apart from a collective mindset shift the world over.

Travel

So travel. Take your children. Tell your friends. Let your mindset be changed.

When we are no longer able to change a situation—we are challenged to change ourselves.

–Viktor E. Frankl

Our No Compromise Clause: We carefully screen all contributors to ensure they are independent and impartial. We never have and never will accept advertorial, and we do not allow advertising to influence our product or destination reviews.