Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in Overland Journal, Fall 2007.

After crossing the Rio Pico Mayo we entered the Chaco, the vast semi-desert area of northern Argentina. During the rainy season, the Chaco floods, and the clay soil makes travel nearly impossible. In the hot, dry season, the scrub forest sheds its leaves and bares long, sharp thorns.

We arrived in the Chaco dodging potholes and trailing dust. (One year later, the 1994 Camel Trophy would be greeted by glutinous wet clay that encased the Land Rovers’ transmissions and formed a hard tile-like substance when the transmissions began to overheat. Several vehicles experienced transmission bearing failure when the drivers ignored the pungent smell of scorched oil. The smart members of the convoy pulled over and started the hammer-and-chisel job required to remove the insulating hard clay from the drivetrain.)

The roads in the Chaco are all dirt. On the main highways (roads which at home would be signed “Travel at Your Own Risk”), two trucks can pass each other, while the other roads are just wide enough for one large truck. We encountered no other vehicles on the narrow track leading to the Formosa-Embarcación highway junction. There were a lot of kilometers to cover, and several side trails to explore, so we were traveling at what I like to call survival speed: fast enough to cover lots of ground, but not so fast as to be on the ragged edge. At that speed, one can preload the vehicle’s suspension from side to side to glide over potholes and smooth out the ride, versus crashing into the potholes and stressing the overloaded vehicles—not to mention beating up the passengers.

We reached the junction at about 10:00 a.m., and there met the strangest-looking hobo I have ever encountered. He was right out of a cartoon: tall, thin, and dressed in a frayed tuxedo complete with a worn top hat, tails on the coat, cummerbund, and dirty spats over his dusty shoes. We were in the middle of nowhere and he asked for a ride, but we had no room—and besides, he was heading in the opposite direction. When we told him, he wasn’t concerned and just asked for a smoke instead. We had several smokers in the group, and they came up with a pack of cigarettes and a small cigar. It was as if someone had handed him a bag of gold. He smiled hugely, thanked us profusely, picked up his bundle on a stick, and headed down the road as we headed in the opposite direction. None of us quite believed we really encountered this cartoon of a man, and the radio chatter about him lasted for some time.

On the dusty, potholed highway, survival speed was between 50 and 60 miles per hour. We made good time to Las Lomitas, where we refueled and asked about roads in the area. No one at the station knew about the 4WD trail shown on the map, running along the bank of the Rio Tueco, also called the Rio Bermejo. The plan was to follow this trail for 65 kilometers to a possible spot for a ferry crossing with our inflatables next year. The overgrown track showed lots of promise, and our brush cables got a workout as they bashed overhanging branches up and over the roof racks. We were all smiles as we continued down the track and crossed several large mud holes. It was Paraguay again.

We loved it until the first call came from the rear of the convoy informing us of a flat tire. Then another, and another. Thorns! All of our fun bashing through the brush hanging over the road was leaving a trail of thorns, like Bond’s Aston Martin spewing a trail of spikes. Each Land Rover carried two mounted spares, four extra tubes, a patch kit, and a foot-operated air pump, so we knew we could survive a lot of flats, but changing tires was getting old.

We continued on at a much-reduced pace in hope of not knocking more thorns on the trail. After several more kilometers, the track simply disappeared. The river had flooded at one time and swallowed it. Several of us started hiking to see where the track started again, but after several kilometers, we decided it was a lost cause, and we would pick up the trail again near Laguna Yema. We hiked back and gave everyone the bad news that we would have to retrace our route through the thorns. Every vehicle had now experienced flats and some of them had several.

Back on the main highway, we picked up the pace to over 50 miles per hour, all the while making a game out of gliding over the potholes smoothly. Then a call came from the last car in the convoy about a madman in a Ford pickup who burst through their cloud of dust, passed them at a high rate of speed, and cut it close when he returned to the right side of the road. Soon came the call from vehicle four, Andy Street from the UK, “It looked just like your Baja 1000 when the big Ford howled by and nearly took the bull bar off of my car.” It was John Ayre’s turn next. In true Australian fashion he picked up speed so as to not hold up the maniac in the Ford, but this just pissed off the driver even more. John’s little 2.5-liter Land Rover diesel was no match for the pickup’s howling 6-cylinder diesel.

John quickly radioed Steve Silk and Vince Thompson, who were next in line, to let them know that the Ford’s driver was tired of our dust and was willing to push us off the road to get by. Steve slowed up and moved as far right as the ditch would allow. This was not good enough: the Ford’s rear bumper made smart contact with the 110’s front bumper, although no harm was done. I was in the lead by several hundred meters, and had time to slow way down and move right to the edge of the ditch. The truck came past my Discovery at speed, inches from the door. The driver turned into me as soon as his door passed mine and hooked the gap between his cab and bed on my bull bar.

I was not about to take the 5-foot plunge into the ditch. My reaction was to turn into the truck and floor the gas pedal. The Land Rover locked into the two-wheel-drive truck’s bed and pushed it sideways. When the truck broke loose its bedside was a disaster; my only damage was a slightly bent bull bar and a broken brush cable.

The adrenaline was rushing through everyone. I chased the Ford down, staying right on his bumper, and Steve Silk was right on my bumper with Vince ready for whatever was going to happen. During the short time I was up against the truck’s bumper I noticed a policeman, the same one that I had seen hitchhiking hours before, who had been bumping around in the bed of the truck during this whole crazy scene. His dark skin was now ashen white. When the truck stopped, its two occupants—large blonde German-looking fellows—bolted out of the doors ready to get it on. I was ready too, but being cautious. Steve Silk, half their size, went after them like a pit bull. He was screaming at them in fluent Spanish, asking them what their problem was and demanding their licenses, registration, and insurance card. It started to get totally out of hand with the yelling and threats of violence when the policeman came out of his stupor. He started yelling at the locals and telling them that they better give the information to Steve, and then started chastising them for their actions.

Things finally calmed down, and the Ford took off with the two blonde locals in the cab and the cop back in the bed. The pickup’s pace was far slower than before, and the cop was not being bounced around in the bed. Our adrenalin was still flowing, but several of our team suggested leaving immediately. I asked what was their hurry. We were going the same direction as the truck and I didn’t want to antagonize the occupants anymore by hanging in their rearview mirror. Besides this might not be over. Men who look like they do—who dress well and drive expensive pickups—are important people in the region. There could be more trouble if we crossed paths again.

After about a half hour spent calming down and straightening my bull bar with the help of a winch, we were on our way. The radio was quiet, but in my car, Chris Williams was sure we were in for an ambush. He was scared. I was nervous. One never knows what can happen in the Wild West of South America. Off in the distance, we saw a plume of dust heading toward us. It was a Ford pickup, but this one was blue, not white, and it was full of men standing in the back. As the truck got closer I asked Chris if I was fooling myself into thinking the men were holding rifles. He freaked when he, too, picked up on the rifles—and then pointed out the machine gun mounted on the roof. The adrenalin started flowing again. Chris slid down between the seat and the dash as low as he could get and asked how I could act so calm. Like an idiot I said, “Today is a good day to die!” just like the Sioux Indians would say when entering a battle. It was totally the wrong thing to say to Chris and sent him over the edge. The men were Federales, and I was sure they had been sent to pick us up.

The radio chatter picked up as the truck drew near. Everyone knew we were in for trouble—then the truck slowly drove past, and the Federales smiled and waved.

We were still nervous about having another run-in with our friends in the Ford. The radio was uncharacteristically silent. At dusk, we entered the small village of Pozo del Montero and Vince suggested we stop at the market and get a Coke. This was a good call. It gave everyone a chance to talk and calm down. I described the Ford and its occupants to the market’s owner and asked if they lived nearby. The grocer said he knew them. The truck’s driver owned a very large earth-moving business just west of Laguna Yema. This was our general destination, and an hour later we unknowingly set up camp across the road from the crazy driver’s office.

That night we didn’t think much about the day’s events. We were too busy breaking down tires, patching tubes, removing thorns, and remounting tires. At dawn the next morning we pulled out of our campsite and immediately crossed paths with the battered Ford and its driver. But it was a new day, and he had a new attitude. I guess the police had calmed him down.

We explored the trail again with the same results as the day before. The river had swallowed it for many kilometers and the thorns were again flattening our tires. We did find a spot to cross at the ghost town of San Camilo, but we would have to explore the opposite side of the river near the ghost town of El Pintado to make sure the crossing would be possible. For now, we would head back to Laguna Yema and on to Embarcación, the largest city in the Chaco.

We reached Embarcación and civilization as darkness fell. The first order of business was to find a tire repair shop. We had 11 tires that needed the thorns removed and the tubes patched. While we were working with the tire repairmen, the local TV crew showed up and interviewed Steve Silk about the Camel Trophy. After the interview, the TV station’s owner whisked us off to a Lions Club barbeque. Once again it was southern hospitality at its best.

The next morning we picked up our repaired tires and started to explore the area between Embarcación and Salta. This region backs up to the foothills of the Andes, and since it has a temperate climate it is very populated and modern. The roads were paved and not suited for our needs, but it was our job to explore and get to know all of the through-roads in the region. (It was a good thing we did because during the 1994 Trophy the Rio Bermejo was a raging torrent and there was no way we could use our inflatable rafts to ferry the vehicles across the river.) We spent the night at Parque Nacionál Calilegua. The next day was spent exploring farther south toward Salta, a large modern city, where we would spend two nights of comfort in a hotel.

During our stay in Salta, the photographer and video crew got their material together and sent it by air to England, while Roy, the mechanic, and several of the drivers went to work taking care of the Land Rovers. They were still in good shape and only needed the fluids topped up. Steve Silk and Vince Thompson set up the satellite telephone we carried. In those days, it was a large unit with a dish antenna the size of today’s TV dishes. Steve reported our progress to the office in England and to Iain Chapman, who was in Sabah, Malaysia, leading the 1993 Camel Trophy. The big news was that the US team was in the lead, with France just behind. Jim West and I were very excited to hear those results. We had selected and trained the team and we referred to them as the dream team, because they had all of the skills necessary to win the Camel Trophy.

While the work was going on in Salta, Jim West, Andrew Street, Chris Williams, and I headed back into the Chaco to explore all of the tracks on the west side of the Rio Bermejo, and the ghost town of El Pintado, to make sure that the west bank of the river would allow a river crossing. It would if the river behaved. The Bermejo could be either a raging torrent or a shallow, quicksand-filled trap. Chris Williams was, as usual, creating a route book complete with GPS waypoints. His book was a work of art, very accurate and easy to follow.

We met Hernan Uriburu, who was to be our guide from Salta to Socompa Pass, at the hotel for breakfast. Hernan is a white-bearded mountain man who has a lifetime of experience exploring the Argentine Andes on foot, horseback, and in vehicles. He knows all of the roads and trails in the region, and all of the important people. More importantly, Hernan knew the type of roads we were looking for. The next six days were a fantastic 4WD tour of the Andean foothills and the high Andes. The foothill region, with its arboreal cacti virtually identical to saguaros, reminded the Americans of Tucson, Arizona, and the red rock sand washes made Jim West and me feel at home. Jim is from Phoenix and I live in western Colorado. This was a relaxing part of the pre-scout. Chris Williams, of course, was very busy producing the route book, but the rest of the crew kicked back and enjoyed the scenery. Several times we came upon washouts that had to be filled in before we could pass. The crew relished this work. Most of the washouts were repaired with picks and shovels, and one very large washout was temporarily filled with all of our spare tires.

At a very remote crossroad, we met a couple of gauchos in a 4WD Ford pickup; they looked just like cowboys from Texas. The older gaucho wore blue jeans, a checkered shirt, and a straw cowboy hat. He had the look of a bull rider. Hernan introduced us to Polo and his son. Polo was going to guide us across a remote portion of his estancia. I asked how large the estancia was and we were amazed when he said it was 2,200 square kilometers. The route we were to follow was a road built by Polo’s grandfather, but it had not seen a vehicle for 50 years.

Polo had crossed the route several times on horseback and he had no problem finding his way. The problem was with me. My Spanish is very poor and I did not always understand Polo’s directions. He was sitting in the back seat, and he started tapping my right or left shoulder to indicate the direction I should go. He and Hernan had a good laugh when I still turned the wrong way, and Polo would slap me on the back of the head to say I got it wrong. I started paying more attention after the first slap. We camped at sunset in a red rock canyon that lit up with a pink glow when the departing sun hit the canyon walls. The photographers were in heaven.

We got going at sunup and had a day of great four-wheeling, bashing up and over the many sand washouts we encountered. Polo’s road had completely disappeared and we were following the line of least resistance toward a crack in the distant mountains. Late in the afternoon, we entered that crack and followed the creek to the small town of El Carmen. We were met by many of the town’s residents and Polo’s sons. They were very happy to see Polo in one piece. Polo’s family and friends had expected him to return after one day and they were very worried when it took a day longer than expected. Polo turned out to be more than just a rancher. He owned the town, the cattle business, the farms, vineyards, winery, and all of the other businesses associated with El Carmen. A great dinner was served at the winery, and of course, everyone enjoyed some of Polo’s wine.

During our night in El Carmen, John Ayre turned on his handheld radio, which was tuned to the commercial airlines’ frequency. John had brought the radio so he could communicate with the airliners if we had a life-threatening emergency. The radio chatter that night was about the massive cloud of ash released into the atmosphere by Volcán Lascar. The air traffic controllers were diverting aircraft away from the cloud, which was 250 kilometers northwest of our location, but two days later that cloud caught up with us at the town of Cachi. It was a miserable experience. The ash was very acidic and it burned our eyes, nostrils, and mouths. We wore bandanas around our faces, like bandits, to help relieve the misery. The ash cloud was a gray fog that blocked out the sun in Cachi.

At Cachi we refueled, but this time we used a mixture of 20 percent kerosene and 80 percent diesel. We did this to keep our diesel from waxing in the cold weather that we were about to encounter in the high Andes. The high elevation and cold nights would be a problem for both the vehicles and their occupants. We continued our exploration under Hernan’s guidance. The mountain roads were fun to drive and the scenery was magnificent—vast grassy slopes with snow-covered volcanoes in the background. Hernan had a sharp eye and he pointed out herds of guanaco (a species of wild llama) that we would never have spotted. We spent a cold night outside of La Poma, altitude 3,015 meters (9,892 feet). John Ayre, Jim West, and I had very warm sleeping bags and we had no problem sleeping. The Brits, on the other hand, spent a very uncomfortable night in their lightweight bags.

From La Poma, it was a very steady climb to Abra del Acay, the high point of our trip at an elevation of 4,895 meters (16,060 feet). No one in our crew had ever been that high before, and over half of the guys developed headaches.

The turbo-diesel Land Rovers puffed black smoke and we could feel a power loss, but they climbed the pass without a hitch. On top of the pass the wind was howling and it had cleared the nasty volcanic ash. The views of the Puna (the high grassland that makes up the Andes in northern Argentina and Chile) were spectacular. The problem was that the wind was so strong it tried to blow Jim West, who does not weigh much, right off the mountain. Even the larger members of the crew were buffeted severely. When we opened our coats to the wind we were slammed against the Defender 110 2 feet behind us.

We drove over the pass to Santa Rosa de los Pastos Grandes. I had concerns about snow on the high passes when we returned in 1994. Hernan was not sure when the first snows typically fell, but he knew one of the teachers at the local school, so we stopped and asked about the weather. Hernan’s friend said snow normally did not fall until late in May, except during El Niño years, when it fell much earlier. We would have to check the weather carefully next year because a heavy, early snow could strand the Trophy in the mountains.

Santa Rosa sits at 3,991 meters (13,094 feet), and as soon as the sun set, the temperature plummeted. The teachers invited us to spend the night in one of the school’s bunk rooms but said we would have to provide our own food since they only had just enough to feed the kids. Budgets were tight and they were just getting by. We shared our desserts with the kids and the next morning we gave all of our food except for one day’s worth to the school. We could resupply in Chile. We thanked the teachers and said goodbye. The sad part was also saying goodbye to Hernan. He had become part of our team, but he could not cross the border.

When we stepped out of the school the cold air bit our exposed skin. It was 11°F. My Discovery started up, belching smoke. It did not like the cold. The Defenders started, sputtered and stalled. The fuel had waxed in the fuel filters, which were located low enough in the engine bay that the wind could refrigerate them. We waited for the sun to warm everything up and finally were on our way to Socompa Pass. The twisting roads were fun to drive and the scenery was superb: snow-capped volcanoes, salt flats, odd canyons, and the flamingo-filled Lago Socompa.

We arrived at the 3,558-meter (11,674 feet) pass at dusk. The pass was also the border between Argentina and Chile, two nations that do not care for each other. A football (soccer) pitch was set up on the right side of the road—and the midline was the border. Each country’s flag flew behind its goal post. On the Argentine side, the border post was a nice building, and the non-uniformed customs agents had their act together. They checked our papers, signed the carnets, and acted very professional. When we crossed to the Chilean border post things were very different. The building was in need of repair, and the uniformed guard did not have his act together. It was doubtful he could even read. He certainly had never filled out the necessary paperwork before. He would not even look at our paperwork, which included a letter of introduction from the general who controlled the border guards. He kept going on about checking us out with Interpol before he would allow us to pass into Chile. The sun had set and once again the temperature was plunging.

While Steve Silk tried to convince the guard to allow us into the country, I began thinking about the minefield that Iain Chapman had talked about in January. Argentina and Chile had almost gone to war in 1978 and they mined all of the mountain passes. Argentina had cleaned up their mines, but Chile had not. In Chile, they had also mined parts of the Atacama Desert. I was getting a little nervous again.

It became too cold to stay outside in the cars, so we moved into the border post, which was heated with a wood-burning potbellied stove. The hours were ticking by as the border guard refused to deal with our paperwork and claimed he was waiting for a reply from Interpol. We figured he was stalling for a bribe. Steve was not going to pay him to enter the country since he had already arranged passage with the general. The standoff continued until after midnight when Steve and Vince broke out the satellite telephone and threatened to call the general. The guard then gave in. He had seen the general’s stamp on the letter but figured he could bluff us into giving him money. Steve and the doctor, who both were fluent in Spanish, figured out how to complete all of the paperwork, and they showed the guard where he should sign all of our papers and stamp our passports.

On the way to the door, I asked Steve to talk to the guard about a way through the minefield. The guard pulled a piece of cardboard out of the trash and drew a map to the minefield. Then he explained how to get through: “You know you are at the mined area when you see a green steel fence post with a paint can lid attached to it that has a skull and crossbones painted on it and the words Peligro Minas. There is a wire attached to the post that runs the length of the minefield to another post. Keep the wire on the right side of your vehicle and stay close to the wire.”

I asked, with Steve translating, how they figured out how to negotiate the mines. The guard replied that five teenagers from Antofagasta had driven their old Land Rover toward the pass, and were all killed when a mine destroyed their vehicle. The military was then forced to make a path through the mines. He also said that the destroyed Land Rover was on the left side of the path through the mines. He cautioned us to not go near the destroyed vehicle and not leave the main road for 68 kilometers from the border. There were mines all over.

I did not feel confident at all about crossing the minefield, and the crooked guard did not help my confidence. It was about 1:00 a.m. when we left the border post and headed toward the minefield. The radio chatter from the cars behind me was not helping my confidence. John Ayre had to comment, “Ya know mate, a Defender 110 can take a hit from an antipersonnel mine. It might blow the tire, but it won’t penetrate the floorboards. We experimented with that when I was in the Australian Army, but I hate to tell you that these are antitank mines, and if you hit one—you’re done.” Farther down the road the radio crackled to life again and posed a question. “Collins, are you red mist yet?” The gallows humor wasn’t helping me, but it was cheering up the rest of the crew. Chris Williams wasn’t amused either since he was in the lead car with me.

After a few kilometers, I spotted what looked to be a house. I radioed Steve and asked him to come with me and knock on the door and see if anyone there could confirm the border guard’s directions. We left the cars about 30 meters from the house and started walking toward the front door. Halfway there we were surrounded by men in black ski masks and black uniforms with no insignias. They pointed HK 91 assault rifles at us.

I thought we had stumbled into Shining Path guerrillas or some other crazy group. We were held at gunpoint for a short time that seemed like forever when the leader showed up. He turned out to be a colonel in the Chilean Special Forces, and they were on maneuvers.

Once again we were saved from endless questioning because the colonel was a fan of the Camel Trophy and had known we would be in the area. I showed him the cardboard map and he confirmed that it was correct. He then added that he knew a route to the minefield that was safe, with the roads that were more Camel Trophy style than the main route. He drew the new route on our cardboard and sketched in an interesting route to the coast. The colonel cautioned us not to leave the roads, because mines could be anywhere.

When we returned to the cars, Vince (a former SAS member) appeared out of the darkness. He had vanished into the weeds when the armed troops surrounded Steve and me. He said, “The troopers did everything perfectly. You two were going nowhere. The American Special Forces must have trained them.”

I felt much better about getting through the minefield now. When we arrived it was just as the border guard described. The guys were making all kinds of noise over the radio trying to get a rise out of me. Jim West came up with the best comment: “Nice way to fake a minefield. Put up a sign and throw in a wadded up Land Rover for effect.” I asked him if he would like to test his theory, but he declined.

We made it to kilometer 68 after getting lost for a while in the bright lights of a huge copper mine. At kilometer 69, near Pan de Azucar, we pulled off of the road and laid out our sleeping bags. It was –2°F. I woke up just before dawn to a stomping sound. When I stuck my head out of my sleeping bag I saw a very strange sight. The British video crew was lighting newspaper on fire and dancing in the flames to warm their feet. They were frozen. We decided to just pack up and head to the Pacific Ocean at Antofagasta. My Discovery started, but the Defenders struggled, and when they did start they strained to keep running on the waxing fuel. Lucky for us, the air was calm and the fuel had not become completely solid.

We headed down the slope of the Andes through the Atacama Desert. The temperature rose steadily. At Antofagasta, it was actually warm. We got a day room at a very nice hotel and everyone took a long shower. We then had breakfast where we met members of the Chilean Four Wheel Drive Club, who were about to lay out the Raid Atacama. I asked them about the mines and they said they always had two military trucks run in front of their convoy when they laid out the route, and yes, they did have a military vehicle hit a mine one year.

They asked about our route into Chile and were quite surprised that we came over Socompa Pass. I told them that we had camped at kilometer 69, just out of the mined area, and they raised their eyebrows and told us we were very lucky. The mines end at kilometer 75.

After breakfast, we started a five-day recce of the Atacama Desert, the driest desert on Earth. It had not rained in Antofagasta since 1927. The only life is found along a line where ocean fog provides some moisture. The rest of the desert is void of all life. No grass, no bugs—just sand, rock, and salt. We returned after the desert scout to the hotel in Antofagasta to clean up and get some rest before the long drive to Santiago, where we would leave the cars and fly home. We didn’t get much rest, because our friends from the 4WD club invited us to dinner and introduced us to their favorite drink: Pisco Control, a wicked spirit similar to tequila. Jim and I were in a celebratory mood when we heard the American Team won the 1993 Camel Trophy. The first American Team to do so.

1994 Camel Trophy Statistics

Vehicles

Discovery 5-door 200Tdi

Number of teams

18

Number of nations represented

18

Route

Iguazu Falls, Argentina, to Hornitos, Chile

Distance

2,590 kilometers (1,609 miles)

Teams

South Africa, UK, Spain, Canary Islands, Greece,

Russia, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Scandinavia,

Poland, France, Netherlands, US, Japan, Turkey,

Hungary, Belgium

Winner

Spain (Jorge Corella and Carlos Martinez)

Team Spirit

South Africa (Etienne van Eeden and Klaus Hass)

Second

UK (Damian Taft and Mark Cullum)

Special Tasks

First: Spain

Second: Switzerland

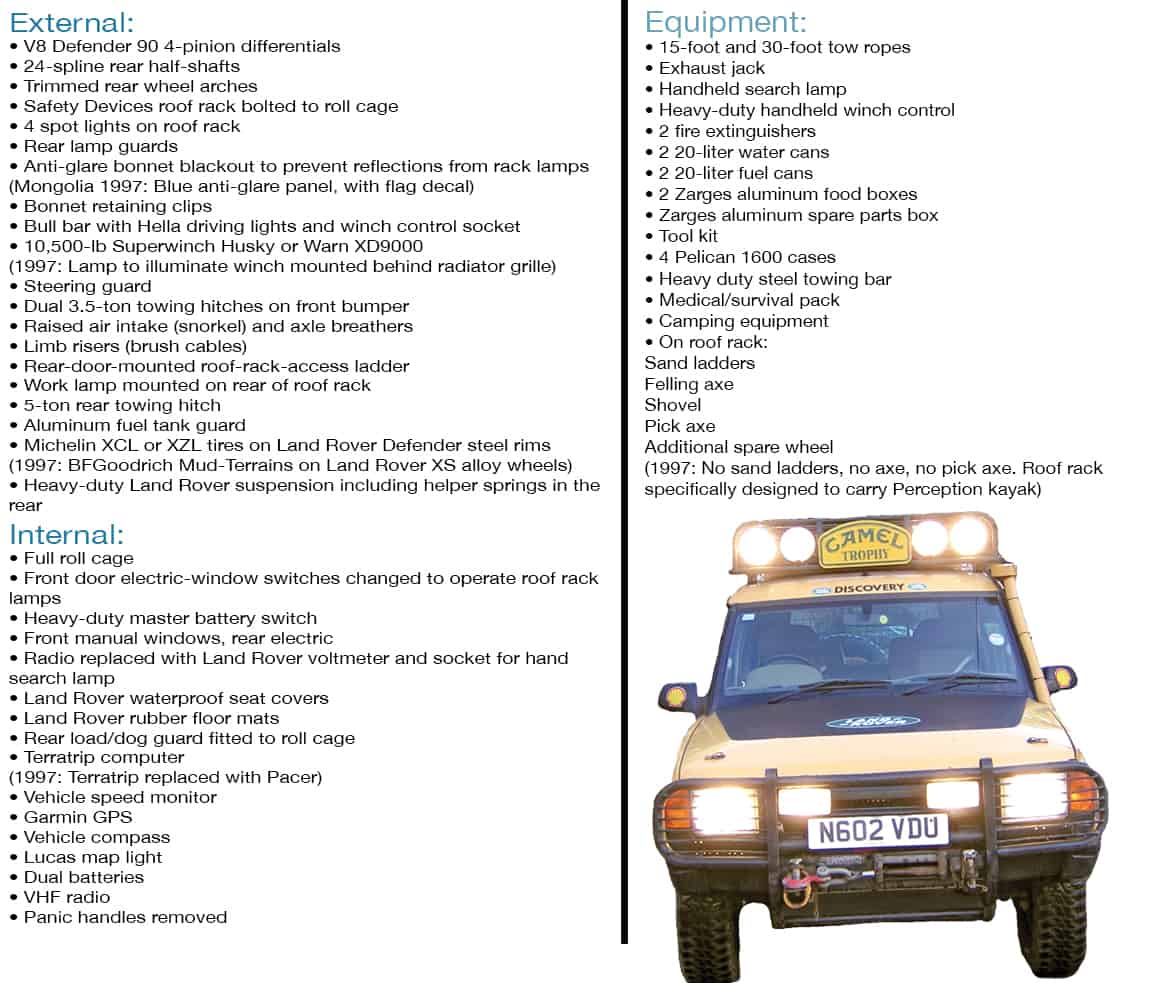

VEHICLE FILE

Camel Trophy Land Rover Discovery

Modifications and Equipment

(all years)

Discoveries were used in the Camel Trophy events from 1990 through 1997. From 1990 to 1994 the vehicles were equipped with the 200Tdi engine; from 1995 to 1997 the 300Tdi was used. Modifications and equipment were essentially identical for each year except 1997. The biggest variation was with the winch supplier. In the 1997 Mongolia event, the vehicles underwent some changes as noted to reflect the change of focus from off-road driving to physical challenges.

3 Comments

Christopher Holewski

August 23rd, 2018 at 7:44 amThe title of this article said “Part 2” – where is the link to part 1?

Keith

September 3rd, 2018 at 11:43 pmGreat story. I wonder if the mines ever got cleaned up?

JIm West

October 11th, 2018 at 6:26 amTC is one of the best story tellers out there. It has been a true honor to know him and have some great adventures with him. He did leave out quite a few “other” stories of this adventure….thankfully.