“Oh, by the way, you will also have to figure out how to get through the minefield in Socompa Pass.”

Iain Chapman, the Camel Trophy’s managing director and field marshal, delivered those words in a thick Scottish accent as we walked past Eastnor Castle’s garages. I stopped and turned toward him and said, “You are putting me on, right?” He chuckled and said, “You’re resourceful. The job will get done.”

I had just been handed a dream job as the 1994 Camel Trophy pre-scout team leader, but the thought of working out a way through a minefield made me wonder if the job would turn out to be a nightmare. It was January 1993, during the Camel Trophy international driver training at Land Rover’s 5,000-acre Eastnor Castle Estate in England. I had until the end of April before our team of 13 specialists would gather in Argentina to explore and create a tough 4WD route across South America for the 1994 Camel Trophy.

All I had to work with was a map of South America, with a line drawn from Iguazu Falls, Argentina, through the swampy heart of Paraguay, and across Socompa Pass to the Pacific Ocean in Chile. It wasn’t much to work with, but it was a start. We had a very talented team with more than 30 years of combined Camel Trophy experience. They would put together a challenging and exciting route. I now had four months to get over my nervousness, while the Camel Trophy Organization took care of the permissions from each country, and found several local guides and MacGyver types to help us find our way through the bureaucracies and across lands seldom traveled.

On April 23, the team of 13 arrived in Buenos Aires from the US, England, France, and Australia. Our specialists were comprised of a doctor, five off-road drivers, a photographer, a Land Rover factory mechanic, a three-man video crew, a pro-rally co-driver in charge of producing a route book, and Steve Silk from the Camel Trophy office, who was our interpreter and organizational expert. I had the dual role of driver and team leader.

In Buenos Aires the drivers split up; some gathered supplies for the trip—large-scale maps, food, medical supplies, tools, and various other items—while the others prepared their gear and the Land Rovers. Getting detailed maps of northern Argentina proved the most difficult task. Most South American countries do not allow civilians to possess detailed topographical maps. Our local MacGyver spent a lot of time convincing the authorities that it would be safe to trust us with maps. It helped that the Camel Trophy was a very popular event in Argentina and that the Argentines considered trophy competitors motorsports heroes. We finally secured the maps that would allow us to navigate the remote tracks in Argentina, but we still had no maps for Paraguay or Chile.

On April 27, we joined the Buenos Aires commuter traffic, winding our way through the city heading for the Argentina–Brazil–Paraguay border at Iguazu Falls. Our convoy of one Camel Trophy Discovery and four Defender 110s caught the attention of bored commuters, who honked their horns and waved as we drove out of the city.

In Argentina, vehicles are left-hand drive, like cars in the US. Our Land Rovers were right-hand drive, English style. This made for some interesting times passing slow trucks. The co-driver had to make the judgment whether to pass or not, and there were some close calls until we got our teamwork down. We also learned that the lead cars could not drive at the speed limit without leaving the rest of the convoy far behind as we worked our way through the slow trucks and farm equipment on the roads. The Camel Trophy day starts before dawn and ends in the wee hours of the following morning. This means that there are a lot of hours of driving in the dark during the short days of the Southern Hemisphere’s late autumn. We had some nerve-wracking encounters with trucks that had logs hanging out well beyond the end of their trailers, which had no taillights. We were constantly on the radio letting the others know what dangers were ahead.

The convoy arrived at Iguazu Falls well after midnight, but we had the luxury of staying at a hotel. This was a nice change from camping in the Buenos Aires Land Rover dealer’s parking garage. The next morning we pored over the maps and laid out a route through Argentina. The plan was to explore all of the tracks near this route and get to know the region. We still had no idea what to expect across the Paraná River in Paraguay. We spent the rest of the day exploring the falls (second in size and splendor only to Victoria Falls in Africa) and the surrounding area. At the end of the day, we ended up in Eldorado, Argentina, where the mayor and chamber of commerce whisked us off to a grand barbecue. We were shown true southern hospitality and enjoyed the Argentine specialty, huge tender steaks. The officials were very excited that the Camel Trophy ’94 competitions would be held nearby.

We camped in the town park and arose well before dawn to start our exploration of Paraguay. The ferry from Eldorado to Puerto Mayor Otaño, Paraguay, was out of commission, so we had to find another ferry to cross the river. But none of the locals knew of any running ferries within a hundred miles. We headed south along the river road looking for any boat that could get our convoy into Paraguay. At the tiny town of Puerto Triunfo we found a rough barge that was ferrying cattle from Argentina into Paraguay. Steve Silk made a deal with the gauchos and they hauled our Land Rovers across the Paraná River two at a time.

There is no town on the Paraguay side of the river, just a shed that serves as a border post where cattle brands are checked. Vehicles and international travelers never cross into Paraguay here. When we arrived at the checkpoint, a 14-year-old border guard pointed his M16 at us and began shaking nervously. He had no idea what we were doing there, and our khaki uniforms and sand-glow-colored Land Rovers probably looked like the beginning of an invasion from Argentina. It took a lot of calm explanation, as the whole team sat down on the side of the road with their hands in plain sight, to get him to lower his rifle and regain his composure. We then had to convince him that we would not move until he returned with the commandante, who would take care of our invasion. The commandante turned out to be a very experienced sergeant who allowed us entrance into Paraguay because we had our paperwork, carnets, and visas in order and, more importantly, because we had a letter of introduction from the minister of tourism and attorney general. We lucked out, because the military often does things its own way and ignores the government’s wishes. Paraguay had only been a democracy for a few years.

We were in Paraguay, but without a map, our convoy was going nowhere. Steve had set up a meeting with the minister of tourism at a dirt crossroad north of our present location, but we had no idea when he would arrive. We spent half a day waiting, but we did not waste the time: we learned how to use the GPS unit in the Discovery. In 1993, GPS units were rarely seen by anyone not in the military, and cell phone service was unheard of in remote areas. It was a great relief when Olavo Chavez, the minister of tourism, and Javier Parquet, a Harvard-educated attorney from the justice department, showed up with their driver in a heavy-duty, two-wheel drive Toyota pickup. They turned out to be great guys who were very excited to show us their country. They also brought a detailed map that showed all of the remote tracks in Paraguay. Now we were ready to get started with the adventure. There was a hitch though: we were not allowed to mark the map and we could not keep it. That didn’t matter though since Chris Williams, our rally co-driver, knew how to keep an accurate log and make a route book that would render the map unnecessary when we returned in 1994. The GPS also would prove to be invaluable in keeping us oriented.

We had no idea what to expect in Paraguay. Very few people from the outside visit and fewer yet explore its remote tracks and trails. The first area we explored was Puerto Mayor Otaño. It was a shock to see how different this town was from its neighbor across the river in Argentina. Puerto Mayor Otaño is a very modern farming town, complete with John Deere, Caterpillar, and Ford dealerships. This rich agricultural area turned out to be the German and Japanese colonies that were noted on the map. Immigrants from those two countries, along with a handful of Americans from Pennsylvania, had turned this former jungle into productive farms.

Over the next three days, we explored all of the through tracks between the Parana and Paraguay Rivers along the line that Iain had drawn on the map of South America back in January. This is a land of large cattle estancias, where horses and ox carts are still normal modes of transportation. The only fuel stations are in the region’s two largest towns, Caaguazu and Rosario. Fortunately, we could cover a lot of miles between stations— the 2.5-liter turbodiesels are very fuel efficient, and we carried 10 gallons of extra fuel in the Discovery and 20 gallons on the roof of each Defender.

Our guides knew this area very well. Their relatives owned many of the estancias, and they had been coming to this region since they were children. A friendly rivalry began between the four-wheel drive Land Rover crews and the two-wheel drive Toyota crew, who claimed that their turbodiesel pickup could go anywhere those fancy Land Rovers could go. I have to admit that their driver was one of the best I had ever seen. He succeeded in leading the way through some very rutted and washed-out roads. The Toyota had large tires, lots of ground clearance, and a positraction rear end, but it was the driver and his ability to pick the right lines through the tough sections and use momentum to his advantage that amazed us all. Our Paraguayan guides did a fantastic job of navigating to Rosario on the Paraguay River, but they had never set foot in the region beyond the river, except along the main paved highway that bisected the country from Asunción to the Argentine border. Their map, our GPS, and our experience navigating overgrown tracks would be the tools necessary to make it through the swampy Vayandi Forest to the Rio Picomayo and the Argentine border.

At Rosario, our doctor, who was fluent in Spanish, arranged a barge to ferry the convoy across the river. The rest of the team checked over the vehicles and their personal gear, while Steve and I arranged a small plane at the local dirt strip to do an aerial scout over the swamps that Iain wanted us to traverse. We flew the whole area from Rosario to Asunción, the capital of Paraguay, and from the Paraguay River to the Argentine border. It was nothing but water with very few roads and trails traversing the area. The pilot informed us that the region was experiencing a drought and the water was at its lowest level since 1985. He told us that the only way through the swamps were the estancia tracks due west of Rosario, and that they would be very difficult if it rained. That is what we were looking for: muddy tracks that required winching and hard work. Now all we needed was rain during the actual event the following year. For now, it was dry except for a few large mud holes scattered along the trail.

We crossed the river without any problems and headed west through the estancias. Olavo and Javier were impressed that we could navigate through the tracks and trails that had sections overgrown with tall grass, without missing a turn. It wasn’t long before we started crossing the mud holes. The Toyota traversed the first hole looking like a television ad, with mud and water flying 10 feet high in all directions. The truck was now dark gray, and stinking of tropical mud. At the next hole the Toyota was simply swallowed, while the snorkel-equipped Land Rovers drove easily through the deepest part of the mud-filled crater, passing the stranded Toyota. The pickup was snatched out of the mud and we all had a good laugh, while the Paraguayan crew admitted there might be a possibility that four-wheel drive was superior to two-wheel drive. We put the Toyota in the middle of the convoy and continued through the grass and mud. The Land Rovers pulled the Toyota through the worst holes, but they amazed us with their ability to get through most of the day without help.

The Vayandi Forest has a prehistoric appearance. The swamp was filled with huge birds—spoonbills, storks, herons, and ibises—flying through the dense palm forest looking like pterodactyls. Our navigation was spot-on until it got dark and we were on tracks that were completely overgrown with tall grass. Unable to find an intersection shown on the map, we gave up and set up camp—past experience in Africa had shown that one tends to drive in circles when it is dark and the area is overgrown. The GPS said we were camped within 100 yards of the intersection, but we could not find it even with spotlights. At dawn, I took the map and a compass and found the intersection the old-fashioned way. We were parked 50 yards beyond it and the rising sun lit the grass to reveal the track.

We spent the rest of the day driving toward the paved highway through a maze of fences and gates. It was strange that we saw no gauchos. When I mentioned this, Javier explained that it was May 1, Paraguay’s Labor Day, and everyone had the day off. We continued driving along the main road until about 10:00 p.m. that night when we came to a locked white wooden gate that was posted with no trespassing signs. Olavo looked the signs over carefully and discovered that the estancia behind the gate belonged to his brother in-law, so he promptly disassembled the hinges and opened the gate. After reassembling everything, we drove on a graded road for about 15 minutes, thinking that we would soon be arriving at the next gate and the paved highway. Unexpectedly, we came upon the estancia’s headquarters. There were no lights, but a large pit of coals was glowing bright red and dimly revealing the faces of about a dozen men. The music was very loud and the gauchos were stumbling drunk.

The lights from our vehicles startled the merrymakers. The music stopped, and several of the men drew their pistols and surrounded our vehicles as Olavo stepped out of the Toyota. Everyone was nervously anticipating what might happen next. The head gaucho walked over to Olavo, waving his revolver, and screamed, “How did you get past the gate?” Olavo explained that he took the gate apart, and the head gaucho became even more irritated and threatened to shoot him. Olavo was very cool and explained who he was between the gaucho’s threats, and most of the guns were holstered. We were told in a very threatening voice to get the hell off the estancia. It didn’t matter that Olavo’s brother-in-law was the owner or that Olavo was the minister of tourism. No one entered this property without written permission and anyone breaking in would be shot.

We gingerly turned the vehicles around and headed back to the gate. A young gaucho on horseback led the way and made sure that the gate had been put back together properly. Steve Silk talked to the horseman as he unlocked the gate and found out that the road we wanted was about a half-mile away and overgrown with grass. We found the road, drove for about two miles, and made camp. Javier produced a bottle of scotch, and we calmed our nerves with a shot or two before dinner.

The night of the drunken gauchos was soon forgotten as we traversed the grass tracks leading to the Asunción highway. This was the last day with our Paraguayan guides. They planned to cross the paved highway and stay with us to the next crossroads, where they could return to their normal lives as government officials. I asked why they chose that particular spot to return home. Javier laughed and said that the “Road to Hell” was no place for two-wheel-drive trucks and most of the time was no place for anything with wheels. The region is usually covered with 6 to 10 inches of water, and during the rainy season, many areas could be 10 feet deep. Ten feet of water is too much even for Camel Trophy vehicles, but 3 feet of water would make a very interesting, but doable, challenge for next year’s competitors. Our crew was ecstatic to find a road that could take days to winch across. This could be the highlight of the 1994 Camel Trophy.

We drove on, everyone dreaming of the Road to Hell—all except for Roy Hullah, our mechanic, who as usual was fast asleep, eyes solidly closed behind his dark shades as his head bounced in rhythm with the Land Rover 110. Roy awoke three times a day—for breakfast, lunch, and dinner—and only oriented himself during those meals. Lucky for us, the Land Rovers had no mechanical troubles, since if they did we would have to wait for dinner to get the problem repaired.

Roy’s routine was interrupted abruptly when we arrived at the Rio Aguaray Gauzu. A construction crew from Italy was redecking the bridge, and there was no way that anyone was going to drive across a forest of pilings.

The river channel was narrow and the banks steep, but lucky for us, the water was only about 4 or 5 feet deep. The drought had reduced the river’s level by 20 feet and the scoured banks confirmed that. We stood on the bank staring at the logs and construction debris choking the channel. The only thing to do was ignore the piranhas, get wet, find the shallowest part of the river within 100 feet of the bridge, and clean out the debris. There were no trees close by so we’d use the bridge pilings for winch anchors.

Once we decided where to cross, the team went to work winching logs out of the way, and used their backs to remove the rocks and construction trash.

The work was wet and slow. It wasn’t until two hours later that my Discovery was eased over the edge on a winch cable. It took a lot of time to winch it through the 4-foot-deep water and mud-filled bottom to the sandbar on the other side. Winching four other Land Rovers and the Toyota through the ford would take all day. A better plan had to be found.

We held a quick huddle to figure a faster way to cross the river. The ideas came slowly, but then I remembered how we waterskied vehicles across a quicksand-filled river in Tanzania during the 1991 Camel Trophy. I explained the setup, and the team quickly pointed the Discovery toward the bridge, unspooled three-quarters of the winch cable, ran the cable through a pulley block attached to a bridge piling, and hooked the cable to the next vehicle ready to cross the stream. I then reversed the Discovery as hard and fast as it would go up the sandbar. The result was a Land Rover 110 that crossed the stream so fast it barely touched the bottom.

Next in line was the Toyota. As it was not equipped for deep-water crossings, the pickup had to be prepped before entering the water. All of the possible areas that could allow water into the engine and fuel tank were sealed off with rags and duct tape. The truck was then attached to winches front and rear and lowered down the embankment, but not without some drama for the driver. John Ayre, from Australia, and Andrew Street, from the UK, were at the winch controls and they were determined to show the superiority of the Land Rovers in the ongoing brand battle. The Toyota’s front end was raised straight out from the bank with over 10 feet of air under the front tires. It was then lowered to the ground. This happened with mucho gusto and our Paraguayan driver was given an unexpected amusement park ride. His face looked like the photos taken on a roller coaster. Once the truck was at the water’s edge we exchanged the winch cables rapidly and it was skied across the water before the driver could catch his breath. He was covered with sweat after his wild ride, but the truck barely got wet. We then quickly got the remaining Land Rovers across the river.

While this was happening the Italian construction crew completely stopped work to watch our show. When the six vehicles were winched and snatched up the far bank of the river, the Italians cheered and shook our hands. They said they had only seen such work in the Camel Trophy movies and thought it a privilege to see it in person.

We soon reached the crossroads and said goodbye to our Paraguayan friends. Everyone was sad to see them go, but we had no time to think about anything except the Road to Hell. Fortunately for us, drought had boiled the water away and all that was left was a faint sandy track through a forest of scrub, palm trees, and huge hummocks of grass. The route was very difficult to follow, marked only by occasional blazes on the trees. The grass hummocks gave us a lot of trouble. We did not have the ground clearance that an ox cart has and constantly got hung up on the unforgiving mounds of grass. The Camel Trophy vehicles have a large aluminum skid plate to protect the steering rods, and this plate was put to work as we bashed hummock after hummock in what looked like a mad dash through the forest. We employed snatch straps and winches to keep the convoy moving forward every time one of us failed to smash up and over a tough ball of grass and sand. After many miles, the forest opened up and we were able to make better time, resorting to the winches only when a driver did not use enough momentum to climb the sandy banks of the many small creeks that coursed through the area. We had just driven through Hell and it worked us. Everyone wondered what it would be like when covered with water. Many of us would find out next year.

The Land Rovers crossed a steep-banked creek—our River Styx— out of Hell and onto a faint track, then into a chaotic maze of cattle and ox-cart trails that gave us no clue which one led to Pastor Pando, the town that was our goal for the night.

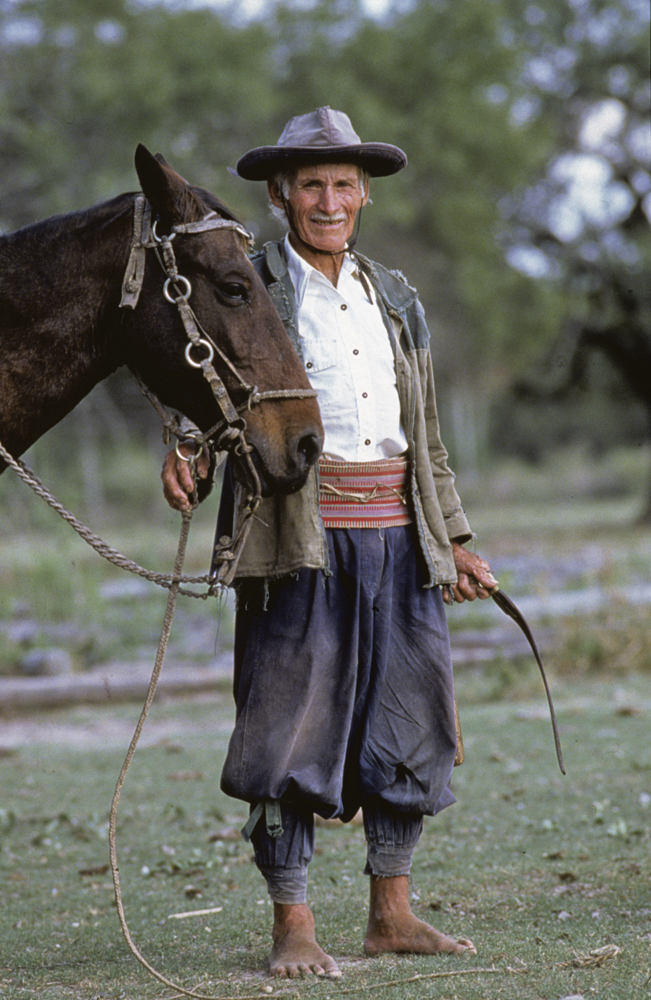

After an hour of frustrating navigation, we came across an elderly gentleman on horseback, dressed exactly like a Spanish colonist from the 1700s. We had entered a time warp.

Don Pedro owned the land all around us. He was very friendly and gave us detailed instructions on how to reach Pando. Our conversation with him was much like a conversation with farmers and ranchers all over the US Midwest. The cattle business was on hard times and the young people had no interest in taking over the estancias. The big city beckoned with excitement and decent jobs, so the sons and daughters left the old folks to carry on. Once again, I was shown that people from every corner of the world share the same feelings and experiences.

We reached Pando just as the full moon was rising, and found ourselves in a small Spanish-styled adobe village with no motor vehicles except ours. It looked like an 18th-century California mission. We had dinner at the hotel restaurant, which was a nice change from camp food eaten on the fly. There was a large world map on the wall, and the Brits became agitated when they discovered the Falkland Islands marked as Islas Malvinas, Argentina. England and Argentina fought a war over those islands in 1982, and the British won. Vince Thompson, a bear of a man and former member of the British SAS, took particular exception to the map. The Brits went to our vehicles and peeled a Union Jack sticker off of one of our tire pumps and placed it on the map over the Islas Malvinas and declared to the locals that the islands belonged to the UK. The locals took one look at Vince, who has the look of a boxer and fists the size of hams, and said Paraguayans could care less about British and Argentine politics. Even the Argentines in the crowd that night were Paraguayan.

The next morning, Sunday, we got a late start. We spent the day after that driving on roads fit for a WRC rally, and pushed the Land Rovers accordingly until we reached the Rio Picomayo, the Argentine border. Once again we surprised the Paraguayan border guards—it is not often that a Camel Trophy convoy shows up unannounced. Our papers were in order and we crossed the bridge into Bruguez, Argentina. After clearing Argentine customs we set up camp in the grass on the edge of the road.

My dreams that night were of what was to come. We still had to find our way through the Argentine Chaco, cross the Andes, and navigate the Atacama Desert—without a map.

4 Comments

stephen gross

December 10th, 2018 at 7:59 amOld article

Alberto DG

December 15th, 2018 at 5:07 amwhat an incredible read!!

Mat

December 18th, 2018 at 7:30 amOlder but a great story and worth the read. Where is part 2?

Curtis

January 11th, 2019 at 7:38 pmGreat article