“The Pamir Highway destroys everything” laughed Farik, as he gaffer-taped my number plate back on. The pannier rack had cracked a few hours earlier, my electrics had failed and Marley had already had two blow-outs. At this rate we’d have no bikes left by the end of the trip.

A few days previously we’d left Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, for a two week recce ride along the Pamir Highway, one of the wildest and most scenic roads on the planet. So named because it cuts through the High Pamirs – the fourth highest yet least explored mountain range on earth – the Highway is legendary for its thrilling riding and formidable scenery. It promised adventure, dusty tracks over distant mountains and the chance to be as close to the edge of the map as it’s possible to be these days.

The start, however, wasn’t quite so glorious. Jet-lagged and jangling with nerves, I shakily steered and stalled my rented Galaxy 250 through the Dushanbe traffic, my toes straining to reach the ground. But we were soon riding east in the shimmering heat, grinning with relief at Farik, our guide, and Anton, our mechanic, the capital’s blacked-out Land Cruisers replaced by trotting donkey carts, lurching Soviet-era trucks and fields of toiling figures bringing in the melon harvest. Oddly, for an Asian country, there wasn’t a single other motorbike.

That night, when a blow-out and a violent thunderstorm left us stranded in a tiny village, we were taken in by a local family, three generations of whom lived under one tiny roof. Pamiris are amongst the poorest people in the world, neglected by their government and largely dependent on aid, but here, the guest is king. Nina, the wizened matriarch, fussed around us, laying on an impromptu feast of non, bread, potatoes, eggs and salad, intermittently holding my hand and calling me her daughter, whilst around us green-eyed children and gold-toothed adults excitedly watched our every move.

When it came to bedtime the three boys slept outside on a raised platform, while I was bustled into the master bedroom to sleep with a young couple, their baby and a dummy-sucking toddler. What an unexpected end to our first day on the road.

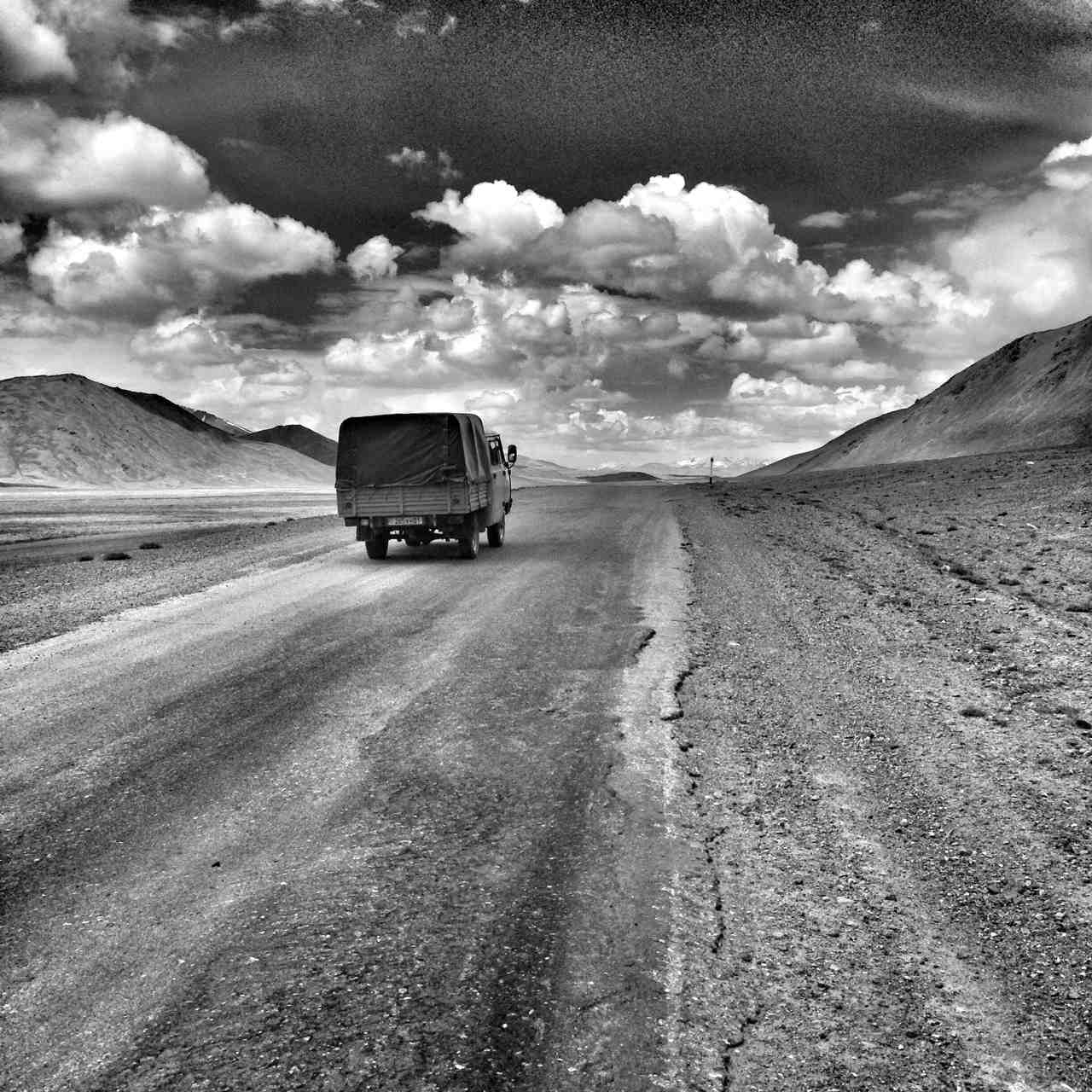

The following few days took us through an ever more dramatic landscape of deep valleys, snow-streaked peaks and blustery mountain passes. By now the M41, as the Highway is officially known, had deteriorated to a gravelly track and we were up on the pegs, bumping over stones and weaving around potholes. At times the road would twist through Tolkienesque gorges of immense depth, great fortresses of rock rearing above, churning rivers below. At others it slung us through wide, lunar valleys where silvery peaks framed the horizon and Chinese trucks lumbered through the sand, enveloping us in dust as they passed. It was a savage, visceral beauty, the likes of which I’ve never experienced before.

After Kala-i-Kumb the road met the Afghan border and we followed it, separated only by the rushing turquoise waters of the Panj River, for the ensuing four days. On occasion the Panj meandered wide and slow, but at others times the gulley was so narrow I could literally throw a stone into Afghanistan. There was a certain frisson to riding so close to this other world, and as I waved at Afghan farmers, with their simple adobe houses, hand-scythed wheat fields and neat terraces of mulberry and pomegranate trees, I wondered what their futures held.

At the regular police checkpoints Tajik policemen, tummies straining at buckled belts, laughingly pointed across the river and said ‘Taliban, Taliban!’ But not for a second did we ever feel in danger.

Nowhere did we feel the ghosts of history more keenly than the Wakhan Corridor, a narrow strip of land created during the Great Game as a buffer between the British and Russian empires. Ibex horns were stacked at roadside shrines, Silk Road fortresses stood like sentinels on mountaintops and the windswept hillsides were strewn with ancient Kyrgyz graves. After one lung bursting walk up to the ruins of a Buddhist stupa, a Wakhi boy furtively offered us a handful of local rubies.

Not for nothing are the Pamirs known as the Bam-i-Dunya, the roof of the world. From the Wakhan Corridor we climbed and twisted north over the 4655 metre Khargush pass, engines straining from the altitude. Fat golden marmots bounded away from our wheels, the only sign of colour in the bleached landscape, and our tyres crunched over sand and gravel. At Murghab, a tatty settlement near the Chinese border, we slept at 3650 metres, our highest night of the journey.

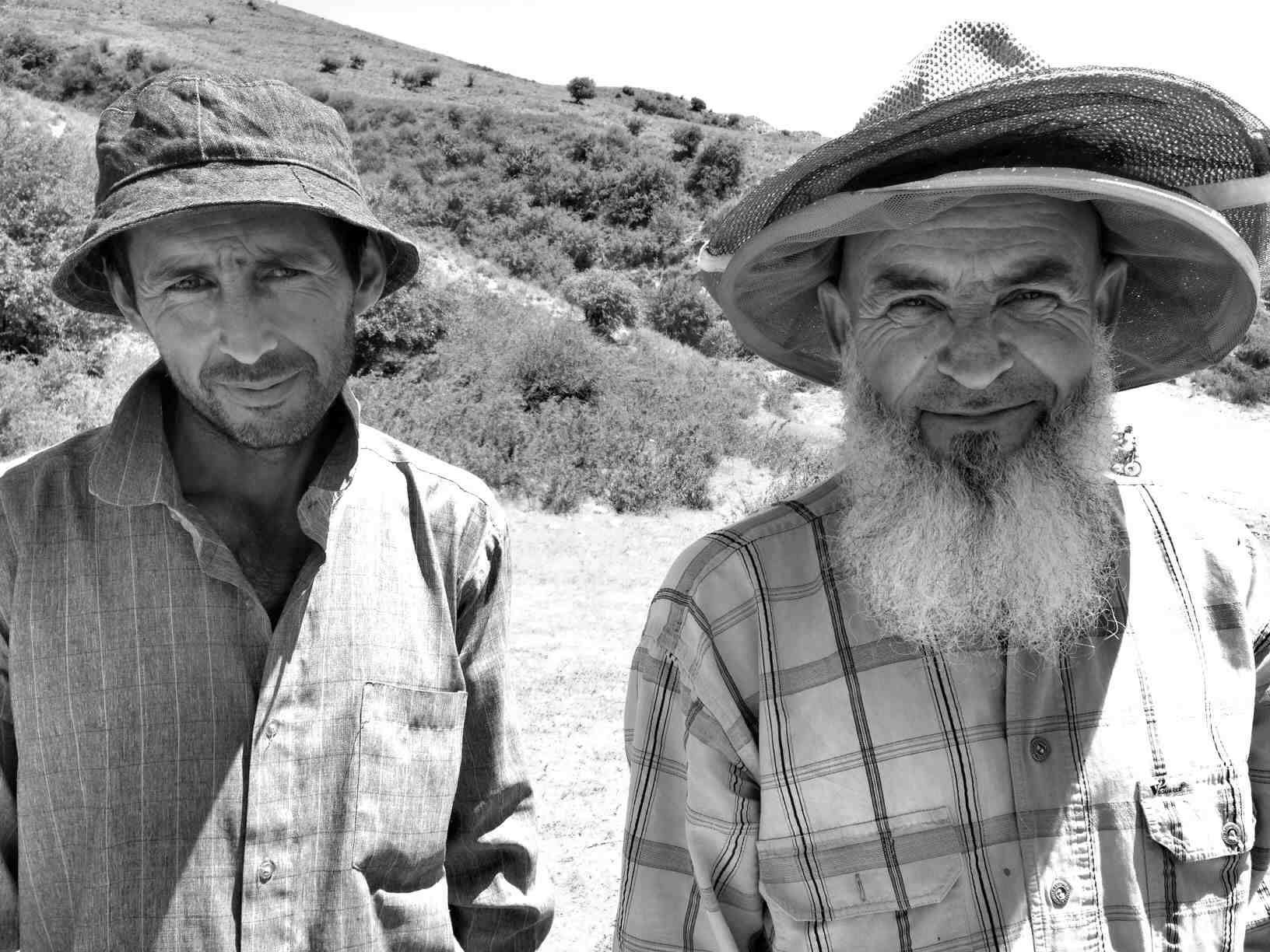

The environment may have been harsh, but the warmth and kindness of the Tajik people was the defining feature of our ride. Smiles as warm as a summer’s day beamed at us from every weather-worn face and I rode, grinning, through villages of shrieking, waving, excitable children. But it’s wasn’t just the children. Everyone, from bent old women leading their donkeys in at dusk, to young men selling apricots in the shade, greeted us with a cheery wave and a heart-lifting smile. In one of the homestays we stayed at, the grandfather insisted on sleeping in an old bus beside our bikes, out of respect for us, the guests. Not that anyone would have considered stealing them, let alone been able to ride them.

Farik and Anton were no different; endlessly enthusiastic and ebullient, and full of quips and smiles.

Make no mistake, riding in Tajikistan isn’t easy. There’s little infrastructure, a distinct lack of luxury, memorable loos, rough roads and significant altitudes. But it’s a corner of the world that remains refreshingly untarnished by the tentacles of mass tourism and travelling here has an exciting, exploratory edge. The scenery is sublime, the people wonderful and the riding thrilling – tonic for the soul indeed.

You can join Antonia next June or July on a 14-day adventure through Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. The small group trip costs £3650 per person, including all accommodation and meals and the hire of a fully-insured Suzuki DRZ400.

To find out more see edge-expeditions.com. You can also find edge on Twitter at @edge_expedition; facebook.com/edgeexpeditions and Instagram as edgeexpeditions.